Wynton Marsalis, “Black Codes” and Thoughts on the Highway

It is midafternoon on a recent weekday and jazz legend Wynton Marsalis is driving across the Southwest, taking the call on speakerphone that his 1985 album, “Black Codes (From the Underground),” has been inducted into the 2023 class of the National Recording Registry.

“Where are we now?” he asks fellow passengers in the car. “New Mexico?”

“New Mexico,” a voice confirms.

Travel has been hectic of late. Marsalis, trumpeter, bandleader, the managing and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York and perhaps the most internationally recognized jazz musician of the era, has just wrapped up a tour in Asia with multiple stops in South Korea and Japan.

The man is 61. He’s been working gigs for 48 years, since he was a 13-year-old child prodigy on Bourbon Street. He’s recorded more than 60 jazz and classical albums, won the Pulitzer Prize, 9 nine Grammys and been a star of numerous documentaries, not least Ken Burns’ “Jazz.”

Now, he’s on the road again, heading east into the middle of America, empty desert stretching out in all directions.

“We left Los Angeles at 12 o’clock midnight — I mean, Santa Barbara — and now it’s 1:51 p.m., where we are, and we’re just in New Mexico.” He’s got time to chat, he laughs.

“Black Codes” is one of 25 pieces inducted into the NRR this year, ranging from 1908 mariachi recordings to a 2012 release of a classical piece by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Ellen Taaffe Zwilich. The Library has nearly 4 million recordings; only 625 are in the NRR.

“Black Codes” is the first recording by Marsalis to make the list. He points out that after a career that spans five decades, the Library selected an album he recorded when he was 23.

“People like it, it’s an OK record,” he allows. “But it’s some (expletive) before I even learned how to play.”

This doesn’t come across as false modesty given his straightforward, cheerfully profane delivery, but as a common assessment of most people of a certain age — who among us wants to be reminded of our work product in our early 20s?

Still, he’s happy to reconstruct the basics.

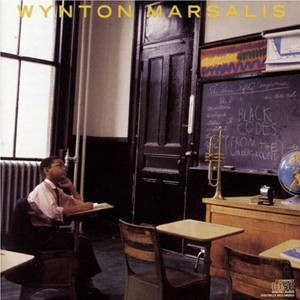

The album was recorded in New York over four days in 1985. It was his sixth record. It’s seven songs of hard-swinging jazz that addressed, if in abstract fashion, the lingering societal effects of the Black Codes, the notorious post-Civil War laws that his native Louisiana and other Southern states used to keep black citizens in a violent state of oppression. One of his brothers, Branford, himself a renowned musician, played sax. His youngest brother, Jason, then just 7, is pictured on the album cover as a school student.

“A lot of 20th-century civil rights cases were based on the Black Codes, on laws that tried to politically undress the achievements of the Civil War,” Marsalis explains.

“From the Underground” refers to Black resistance to those laws: “No matter how defeated things seem, there’s always an idea in the pursuit of freedom that is subversive to anti-democratic thinking. I was very conscious of that (when recording).”

The album cover wasn’t subtle. It’s a schoolroom photograph of a lone black child (the aforementioned Jason Marsalis), gazing at a blackboard where the “Three-Fifths Compromise” — the constitutional measure that described enslaved Black people as three-fifths of a human being — was written out in chalk as the lesson of the day. Part of it is erased. Replacing it are words also written in chalk: “Black Codes (From the Underground).” A trumpet rests on the teacher’s desk.

On the album, the family and cultural inspirations are also practical.

Marsalis drew on his father’s history as a jazz musician and teacher in New Orleans, particularly a 1960s song called “Magnolia Triangle,” for the melody line of the title cut. The bass line was inspired by the classic New Orleans standard “Hey Pocky A-Way,” by The Meters.

“We live here for whatever our time is, and people represent us in different ways,” Marsalis is saying, the miles whizzing past. “The art forms, of course, speak across time. They tend to speak more successfully than philosophy because philosophy has to be written in a symbolic language that’s easily misconstrued. Art is much more direct.”

by: Neely Tucker

Source: Library of Congress Blogs