The Dignity of His Sound: Wynton Marsalis Talks About The Buddy Bolden Movie

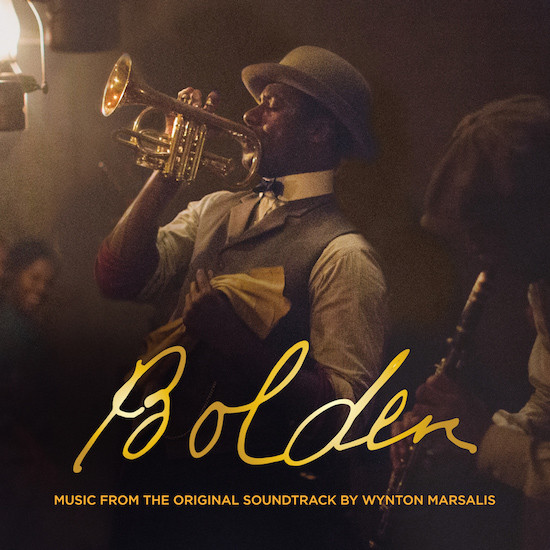

Wynton Marsalis describes the movie Bolden, which is directed by Daniel Pritzker, and will be released on May 3, as a “mythical account” of New Orleans cornetist Buddy Bolden.

“The man is mythical; we don’t have recordings of him, we only know what people say Buddy Bolden was like, but nobody really knows,” says the Grammy-winning trumpeter and composer who acts as the film’s executive producer and who composed and performed on its soundtrack, which will drop on April 29.

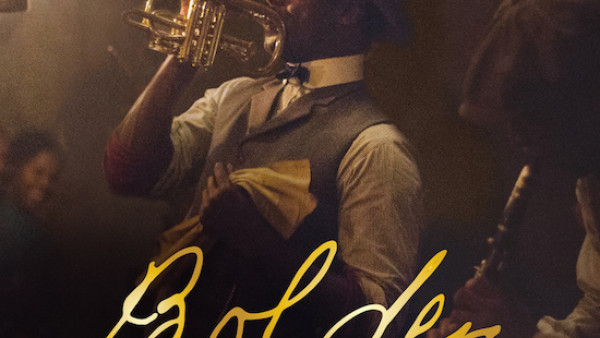

Marsalis is also heard playing the cornet when actor Gary Carr is depicted blowing the horn. He switches to the trumpet when Louis Armstrong, played by Reno Wilson, enters the picture. “This is not a historical drama or a biopic,” Marsalis reiterates. “Dan [Pritzker] had a vision of Buddy Bolden and of those times, and it deals with different issues. It’s not a sanitized version that makes Buddy Bolden seem like he was a preacher.”

Cornetist and bandleader Bolden, who was sometimes referred to as King Bolden, was born on September 6, 1877, and gained a city-wide reputation for his musical talents and the strength of his blowing. He struggled with mental illness for much of his life and died in the Insane Asylum of Louisiana, on November 4, 1931 at the age of 32.

“When I was growing up I heard his name. I heard people talking about him,” remembers Marsalis, who around 1980 read author Don Marquis’s highly researched biography of Bolden, 1978’s In Search of Buddy Bolden: First Man of Jazz. “I love his book, and him,” Marsalis offers.

Though Marsalis has been deeply involved with the movie, he is quick to point out that it is director Daniel Pritzker’s project. “He called me to see if I was interested in doing it,” Marsalis explains. Of course, he was.

Likewise, the movie isn’t based on Marquis’s book, though it certainly played a very important role as an authoritative factual reference. Pritzker also consulted with the author.

The importance of the film to the New Orleans audiences who have long heard about the legend and love the history of their city is paramount. Knowing that Buddy Bolden, who used the music to bring joy to his people and community, will be shared with the world also brings a certain satisfaction.

“I think it makes people aware of that history, and that a man named Buddy Bolden lived and he created the music that he believed in, that dealt with issues of freedom and negotiation of a group,” Marsalis offers. “That’s made clear in the movie. There are racial tensions in America that are still with us today. Destroy their souls and they destroy themselves. The movie also made it clear that Buddy Bolden didn’t grow up in a playground. This isn’t Walt Disney.

“It also sheds a light on mental health issues, because Buddy Bolden lost his mind—and that is a fact—and mental health is an issue today for many people. So, I think it’s good for it to be the subject of something. How a guy with that level of creativity ended up.” That subject is also focused on in the fictionalized novel based on Bolden, Michael Ondaatje’s 1976’s Coming Through the Slaughter.

Following the publication of Marquis’ biography on Bolden, there seemed to be a change of heart by many who had argued that New York or Chicago was the birthplace of jazz. The movie might finally seal the deal that New Orleans owns the rights to that claim.

“Most of the greatest jazz musicians came from New Orleans,” Marsalis states. “It’s like the earliest bones that were found were from Africa. If you want to go back and forth about it [jazz’s birthplace] you can and it’s fun to do that. Are you going to argue with Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong—we could go on and on, the list is endless. Why waste time on that besides the fact that it’s fun to talk about something in a heated fashion especially if there’s no proof and there’s not going to be a resolution to it.”

“Yea, I think New Orleans was well represented in the movie,” Marsalis reflects. “You could see that it was the city and the places and the people, yea. The movie is so internal, and it’s really about the interaction of the characters, but still you know you’re in New Orleans.”

Marsalis was gratified that director Pritzker “let the music play” in the movie; Marsalis felt that, too often in films about jazz, the music tends to take a back seat.

“Dan knew a lot about the material, he did a lot of research, and [clarinetist] Michael White of course knows a lot about this material. We talked for years about what Bolden played. His repertoire, it’s not like it was mysterious; he played music from the church, hymns, he played light marches, he played ragtime.”

Perhaps surprisingly, many of the tunes on the soundtrack were newly written by Marsalis for the project. The familiar classics that appear, songs like “Tiger Rag,” and “Basin Street Blues,” were arranged by the trumpeter for an ensemble that included several musicians from New Orleans, including Marsalis, White, reedman Victor Goines, and guitarist/banjoist Don Vappie.

“I play loud on it,” says Marsalis of one of the ways he approached the cornet with Bolden in mind. King Bolden boasted a huge reputation for blowing the instrument hard.

“What I was doing, I actually idealized his sound—no you can’t recreate it,” Marsalis says of what is heard in the movie and on the soundtrack. “What I tried to do is composite three trumpet players who I know were influenced by him. The first assumption is that the person who invents a style is going to play it better than the people who come right after them. People could play after [saxophonist] Charlie Parker but he played his style better than them. [That’s true] throughout time. Armstrong, Monk, you can go on and on.”

“A person who can barely play is not going to be called the king in New Orleans where people could play. Buddy Bolden was called king at a time when people could play, in a city where people played a lot of music. That means to me, he could play.”

“He also invented more than trumpet parts. That’s why they called him the guy who invented jazz. When he talked to musicians, he was talking about more than the trumpet. If that weren’t the case, he wouldn’t have had that kind of status. He would have just been a good instrumentalist.”

“Another thing, the people who came right after him and actually heard him and competed after him, they could play. Look at who they are, people like Freddie Keppard. People would have a tendency to think that since Buddy Bolden was from a black area uptown, he was not harmonically sophisticated. Not harmonically sophisticated? Environment doesn’t lead to those conclusions. King Oliver is a direct descendent of Buddy Bolden. He heard him all of the time and was inspired to play by him. That makes me know that Buddy Bolden also had dignity in his sound.”

Marsalis went on mentioning the sophistication of Jelly Roll Morton and how trumpeter Bunk Johnson would whistle, incorporating diminished chords that Marsalis credits as having been inspired by Bolden.

By compiling the sound of New Orleans trumpeters who immediately followed Bolden, Marsalis says his aim in blowing his cornet was to represent not only Bolden but the instrument’s tradition in America.

“I made him play rough and with a lot of attack,” Marsalis explains. “I made him louder than anybody and with a lot of dignity. I included arpeggios because every cornetist has to play them,” he adds.

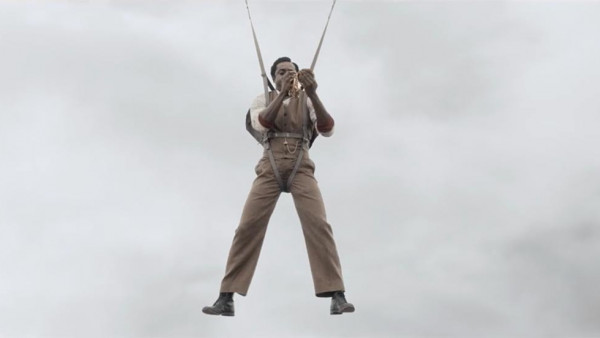

Louis Armstrong, who it’s been claimed, heard Bolden when he was five years old, enters the movie when Bolden hears Satchmo on the radio, while incarcerated in the asylum. Marsalis describes the moment in time as the rise of Armstrong and the decline of Bolden.”

The release of Bolden comes at an auspicious time in New Orleans as there is a renewed focus and effort to restore Bolden’s double shotgun home at 2309 S. Liberty Street. Presently owned by the Greater St. Stephen Full Gospel Baptist Church, the house was by cited by the city for neglect, and threatened with demolition. Keyboardist/vocalist PJ Morton, who is the son of Rev. Paul S. Morton, the bishop of St. Stephen and his wife, Dr. Debra B. Morton, the church’s senior pastor, stepped up and formed the non-profit group, Buddy’s House Foundation, aimed at restoring the legend’s home [read more in OffBeat‘s November 2018 cover story on PJ Morton]

Naturally, Marsalis is aware of the effort and in support of its goal. “I think that it is important for cities to have a sense of significance about their places, the architecture, the physical,” says Marsalis, who compares such locales to part of a “family album.” “Where historical figures lived, their impact on the city and their achievements are great enough to deserve to be commemorated, remembered and preserved. That’s because that achievement and the preservation will create more achievement of the same level of quality and insight.”

by Geraldine Wyckoff

Source: OffBeat Magazine