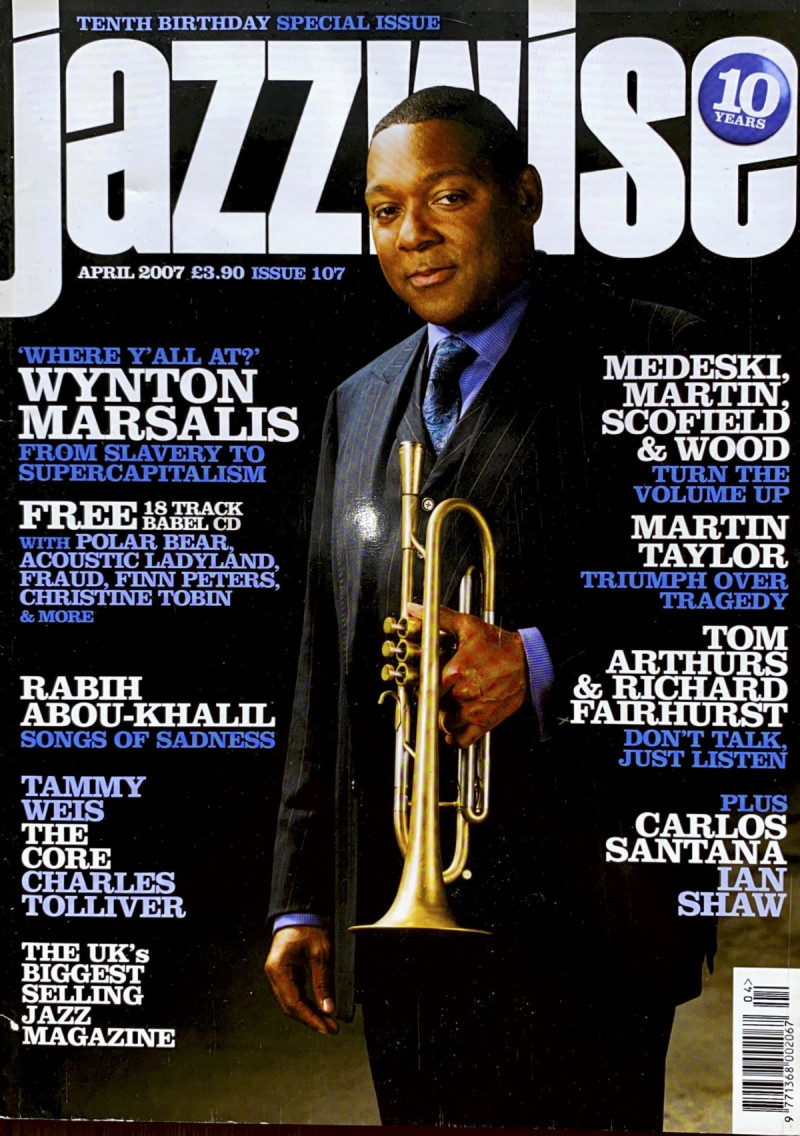

Plantation Polemics: From Slavery to Supercapitalism

Cover: Jazzwise (April 2007)

With his vexed views on the subject of “tradition” Wynton Marsalis, who graced Jazzwise’s first cover ten years ago, has become the epitome of the starchy jazz conservative that many would-be jazz liberals love to hate. Yet is there more to the trumpeter than grandiloquent pronouncements on the need to preserve a particular strand of the music’s history? From The Plantation To The Penitentiary, Marsalis’ new album, reminds us that he is also a fervent political commentator as well as a fine musician. In a frank interview with Kevin Le Gendre, he discusses his despair at the legacy of slavery and colonialism, his love of jazz as dance music and his fears for children growing up too fast in today’s exploitative society.

March 25 marks 200 years to the day that a Parliamentary Bill was passed to abolish the slave trade in the former British Empire. Amid the frightful figures on both the pain and the gain (approximately 17 million deaths, billions ol pounds pumped into the British economy occasioned by this heinous human trafficking, there is perhaps one statistic that stands out above all others. A liberal estimate of the number ol victims of modem day slavery is 20 million.

The past, it would appear, is not over. Moreover the ongoing effects of the original “respectable” trade and its sly business cousin colonialism have been uppermost in the mind of socio-political commentators for many years. The thread between what happened to African slaves then and what is happening to their Diaspora descendants now is Crucial.

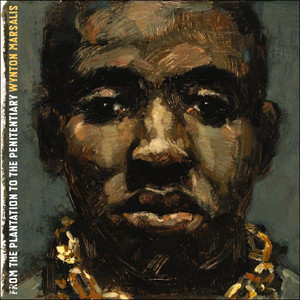

From The Plantation To The Penitentiary, the new album by trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, explores this continuum, offering a forthright opinion on the alarming state of African-American, American and western society. Interestingly the new project wasn’t initiated by anniversaries or specific historical hooks.

“A lot of the views on this record are things that I’ve expressed in interviews tor many years, iterating them in different ways”, Marsalis, who has written all the album’s lyrics, says on the phone from New York.

“The plantation to the penitentiary is a concept that I started to use when I would talk with friends of mine and we would talk about the problems of slavery and how it continues to haunt us today.”

To fully understand where Marsalis is coming from one has to engage in some lateral thinking. “If you were 400 years old and you had been in slavery for the first 250 years and you were segregated for the next 100 years then you had 50 years in which you had to fight tor everything that you got, you would have a very hard time.

“Given modern psychology, where somebody goes for counselling or something, counsellors always talk about your past and how you grew up. Man, those first 250 years you had were very, very rough.

“When I say from the plantation to the penitentiary you had a large population that was forced to work and they were used as a stock the entire country made money off. And then we had a one hundred year dance back and forth trying to keep the people basically in a certain type of economic slavery, then the Civil Rights movement.

“And now we’re doing that same kind of dance again and people can go to jail from that same plantation population for having some herb or type of drugs where it’s ‘I’m liberating you from getting high …. by putting you in jail for 35 years’. It’s ridiculous.”

If penitentiary is synonymous with the misery of black America’s present and future (projections say one in three black boys born in 2007 faces a custodial sentence) than plantation embodies historical woe. Inextricably linked to the dehumanising symbols of the whip, the lash and the bossman, the plantation, that great field of blooded gold in the gallant south, signifies underclass as well as overspill of profit.

Implicit and explicit references to the plantation persist. When Seinfeld’s Michael Richards goes ballistic and bawls out “niggers” who, 50 years ago, would have been “upside down with a fucking fork up their ass”, he is evoking the plantation.

When senator Joe Biden says that black Presidential hopeful Barack Obama is “clean”, he is evoking the plantation. When African-American males make up 26 per cent of the army and only 12 per cent of the American population, they are living on another plantation.

Tableaux of their forebears are to be found throughout Wynton Marsalis’ discography. In 1997 he won a Pulitzer Prize for Blood On The Fields, an emotive, inventive orchestral opus that broached slavery head on. Twelve years prior to that in 1985 Marsalis recorded Black Codes From The Underground, a super1alive quintet album whose title referred to the 19th century laws forbidding slaves from doing the same things as other “legitimate” members of society. In the album’s sleeve notes, Marsalis shed light on the outgrowth of this protocol, on its perpetuation and expansion.

“Black Codes means a lot of things”, he asserted. “Anything that reduces potential, that pushes your taste down to an obvious, animal level. Anything that makes you think less significance Is more enjoyable, Anything that keeps you on the surface.

“The way they depict women in rock videos – Black Codes. People gobbling up junk food when they can afford something better – Black Codes. The argument that illiteracy is valid in a technological world – Black Codes.

In other words the African-American condition was not the only cause for concern. What Marsalis was expressing in 1985 was despair for the general regression in contemporary lifestyle that was graphically epitomised in 2005 by Morgan Spurlock’s Important film Supersize Me. Yet his ire was also directed at popular culture and when he spoke of sexism in rock videos he was glimpsing the future of many rap and R&B promos. Today Marsalis’ voice of dissent chimes with a coterie of hip-hop and soul artists, notably the likes of The Roots, Saul Williams and India.Arie, who have lashed out at the misogyny and glorification ol violence that proves such a money-spinner in “urban” music.

In 2005 Little Brother rammed the point home on The Minstrel Show, an album denouncing the wilful stereotyping of the African-American in contemporary hip-hop. “The modem day minstrelsy… it doesn’t help our knowledge of history”, Marsalis concurs. It helps very little for us black and white because now these are national issues, they’re not just race issues. The kind of traditional racism, which is an outgrowth of the whole colonialism, is not helping the world al this point.”

Persecution of minorities in America and a bellicose, self-serving American foreign policy are not to be dissociated. “I think that there are traditions that are still in place and It’s very hard for us to escape the common history of colonialism and the history of slavery. These things require a tremendous amount of effort to redress.”

As far as Marsalis is concerned everyday language is a good place to start. “The best example is in hip-hop and rap music; the use of the word nigger and calling people bitches and other pejorative terms which are used to the great entertainment of the whole nation, black and white,” says the 46 year-old who may or may not ponder why Ice Cube called himself “a nigger wilh attitude” and then denounced his “slave name” Jackson. “It’s a lot like the minstrel show where they made fun of people for being on the plantation and used the word nigger a lot and then claimed that the real black people had come from the plantations. Now the real plantation is the ghetto.”

While the heartrending spectacle of black America’s second-class citizenship recently came to light (for many unaware Europeans) during the Hurricane Katrina tragedy, there have been myriad indicators of its disenfranchisement for some time. Think high unemployment. mortality and incarceration rates that underpin major commercial interests. A penitentiary can be a lucrative plantation yielding a bitter crop of broken lives.

This has been going on since the 1980s, when crack began decimating America’s inner cities. That decade, the age of Adidas and gold chains, was also the time in which the Marsalis brothers, part of a New Orleans clan headed by father Ellis, made their breakthrough. Emerging from the hallowed training academy of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Wynton and saxophonist brother Branford, wearing neither Adidas nor gold chains, became two of the biggest names in jazz just as everything connected to the music – record companies, sales, audiences – was getting smaller.

After making his eponymous debut in 1981, Wynton, who studied at Tanglewood Berkshire Music Center and then, like Miles Davis, at Juilliard, went on to cut albums like J-Mood, The Majesty Of The Blues and The Marciac Suite. Throughout the 90s his output remained steady, culminating in the 7-disc box set Live At The Village Vanguard. Many monikers were slapped upon him: neo-classicist, young lion, keeper of the flame.

Marsalis’ sharp-suited image and scholarly demeanour marked him out as a man of gravitas as well as an uncommonly gifted trumpeter intent on weaving complex harmony and creative phrasing into improvisations that lost none of the communicative heat of the blues. Along with Terence Blanchard and Donald Harrison, Marsalis brought back some of the sass of New Orleans to jazz in the 80s.

Another key element of the trumpeter’s aesthetic is dance. He has embraced it in a number of ways. On one hand he has scored extensively for ballet, collaborating with such esteemed companies as Garth Fagan. Twyla Tharp and Alvin Ailey.

On the other hand, dance has materialised in Marsalis’ artistic universe in a more “downhome” incarnation. Put simply he has made jazz that you can dance to. A cursory listen to albums such as Thick In The South or Uptown Ruler reveals a clear blues-stamped invitation to shake a tail-feather or at least supplement a fingersnap with a handclap.

On From The Plantation To The Penitentiary Marsalis’ quintet, grounded by the superb drums and bass team of Ali Jackson and Carlos Henriquez and elevated by the arrestingly charismatic voice of Jennifer Sanon, is at its most rhythmically inventive, twirling a wide range of Afro-Cuban and Caribbean beats, from cumbia to soca to habanera, through a tricky carousel of swing. Featuring prominently in the mix is the tambourine, touchstone of the church, harbinger of the Baptist Beat. Yet while this element places Marsalis on similar ground to Don Wilkerson, Art Blakey or Lee Morgan, his music has a developmental intricacy of a different hue.

You could call it post-modern soul jazz but the timbral ingenuity, particularly the wily, tightly controlled dissonance, marks subtle shifts away from that lexicon. Moreover the dominant presence of a vocalist runs decidedly counter to the all-instrumental modus operandi of the aforementioned icons. What jumps out then is Marsalis’ interest in jazz as both art music and dance music. Maybe he envisions the blues straddling the opera house and the street party. We have to look at the trumpeter’s formative experiences to understand why that might be the case. “Well, I grew up playing a lot of dances,” he points out. “I mean nothing but gigs, dances, wedding receptions and big dances that we would do at the top of Gaylords, [in New Orleans] four bands playing all night, packed with people and then clubs. I would say that 90 per cent of the gigs I played were dances.

“Because I played trumpet, when they played the slow songs I didn’t have to play so I’d go out and dance myself!” he continues, chuckling heartily.

“I feel like we made a lot of records with the band with Herlin Riley and Reginald Veal that had a tot of danceable type rhythms on them, New Orleans rhythms. We made records all through the 90s that had those kind of tambourine grooves and drum grooves.

“We wrote three or four ballets that people did dance to, they all had kind of ‘ground rhythms’ and beats, so this music just comes out of that natural progression from that music that we had already recorded.

“Dancing is a part of the tradition of our music. We played a lot of public dances. A swing rhythm is a dance rhythm and the swing rhythm allows dancers to be much more flexible.

“It’s not just the fact that they’re dancing … it’s what are they dancing to? The swing rhythm is a flexible rhythm that keeps you from sinking down into the calisthenic type of dancing.

“It’s just real rigid, machine-based grooves. Machines have a certain effect on you whereas the swing rhythm is more flexible. Every dance rhythm has an identity, like the samba rhythm has an identity; the guanganco has an identity, it creates a certain kind of dance so the identity of the music is wedded to the identity of the dance and the dance says a lot about the vitality of the people, like a bolero has a certain feeling to it.

“It” creates a certain thing and a feeling for people to dance, to embrace each other in one way. A walking ballad creates a certain type of feeling, a swing rhythm creates a certain type of feeling.

“It’s important… as we become more technological, the technology provides us with great tools but we need to, as much as possible, strengthen our relationship to our humanness and our relationship to each other and to communal aspects of living.”

When asked whether he is a romantic at heart, Marsalis – somewhat uncharacteristically – shies away from a statement. Yet he tells me that as a boy he often wrote poems to girls and that he enjoyed “the dance” in which a woman retained dignity.

Other artists think along the same lines. The poet Ursula Rucker has been relentless in her criticism of a MTV-led hip-hop culture in which young women are now happily casting themselves as inferiors, aspiring to be “those girls in a video with no clothes on”, chattel trophies to be ogled.

A complex psycho-sociological syndrome is at the root of this self-objectification but one of the many possible contributory factors is the literal and figurative distance that prevails between revelers in club culture. Dancing is not a unison activity. Dancing is largely an individual affair. With that in mind, the body of the opposite sex is not to be engaged with but seized up. The days of the implicitly sexual corps a corps, a necessary adjunct to the explicitly sexual bump and grind, appear gone.

Marsalis longs for a return of sensuality and civility to modern behavioural norms, an issue not disconnected to the subjects of child rearing and parenting that were placed under the spotlight in that recent headline-grabbing UNICEF report. “If they could incorporate swing dancing into the curriculum of school students it could give them [our kids] a much more romantic relationship to each other.” Marsalis contends.

“But the kind of exploitation of their sexuality has led them to an impasse in their development. The modern day minstrelsy does not help our kids develop into their sexuality; it doesn’t help self-esteem.

“Couple dancing is very important to the ritual of courtship, the dance. I believe in the ritual of courtship. I believe in making things … “ He pauses.

“A man and a woman gonna make love either way and it could be the most primitive or ii could be the most refined. The question of romance is just the style in which you do things.”

One of the prevalent themes of From The Plantation To The Penitentiary is nostalgia for a time passed, a desire to recapture something lost. When Jennifer Sanon sings ‘These Are Those Soulful Days’ she issues a terribly moving plea for a re-assertion of polite society traditions.

It’s almost impossible not to see a parallel between this admonition and Marsalis’ strict adherence to a certain tradition in jazz. Morton. Armstrong, Ellington, Mingus and a be-bopped not Bitches Brewed Miles have been his touchstones, prompting fierce criticism from several tongues within jazz’s Babel, namely the avant-gardistas and fusioneerios. They see him compounding the cliché that progressive jazz gave up its holy ghost in 1967, the year good Saint John Coltrane passed away.

Marsalis’ evolution could be framed in a different way though. It’s Important to remember that he debuted in the 80s, a time of major musical, social and technological developments outside of jazz: the birth of the Compact Disc, the decline of instrumentled education programs under Reagan and the advent of hip-hop. These changes are significant.

With Iha glut al CD re-issues becoming available, dead jazz musicians were brought back to life. Marsalis and the so-called Young Lions performed the important function of being musicians who were real flesh and blood on a stage rather than sepia stills in a jewel case.

More to the point they played instruments to an extremely high standard, something that was soon to be an increasingly scarce praxis among a DJ/producer-led generation. The new religion of hiphop radically remixed age-old sermons. What the lord Beatmaker gaveth with one hand – and it was a lot – he tooketh away with the other. And it was a lot too.

The increased absence of instruments and the erosion of the very concept of the band in black popular music have therefore made the maintenance of virtuosity in black art music all the more important. In other words the real opposition may not be so much between Wynton Marsalis and the avant-garde urban music community.

When, a decade and a half after the Young Lions, urban music deifies Alicia Keys because she can do something unbelievably, astoundingly, jawdroppingly revolutionary, like, play the piano, then you know that something has been lost. There was a time when jaws would have dropped if she didn’t play the piano. And playing is not enough for Marsalis.

“I’m talking about playing virtuosically”, he says, his voice a tad stern.

“It’s two different things. I grew up in an era where everybody played so to actually play is not like ‘Wow! They’re actually playing!’ That’s not a revelation to someone like me. For me I wanna hear them play well. Without any question [standards have fallen].

“I like to hear,” he elaborates, “great orchestrations of things that are textural and to hear things that have a relationship to history, a certain type of richness, a historical richness and above all I love to hear musicians play their instruments.

“That’s why I love to hear a good Beethoven symphony. I like to hear a great symphony orchestra play. I like to hear a great jazz band. I like to hear any kind of great ethnic music which has people playing … flamenco, ragas, tango.

“I really enjoy, above all else, the virtuosity, the expressiveness and the depth of soul of people playing instruments.” This is the common denominator between Marsalis and many players who may or not be his allies in the jazz community.

In any case there can be no denying that some of Marsalis’ work has had a major impact on other musicians. In this country many of the artists who emerged from the Jazz Warriors in the 80s Courtney Pine, Cleveland Watkiss, Gary Crosby, Julian Joseph and Orphy Robinson – regard Black Codes as a pivotal artistic statement.

Why, though, is little mention made of that record? Or Blood On The Fields? Or All Rise? Possibly because Wynton Marsalis the polemicist motor mouth has come to eclipse Wynton Marsalis the musician. The irony is that it’s much more interesting to talk about what Wynton Marsalis actually plays than what he says.

As director of Jazz At Lincoln Center he has power. He’s opinionated, pompous and pontifical but Marsalis’ dogma is not the only component of his make-up. If he’s sadly missed the point over what electricity did for rather than to Miles Davis, or hasn’t understood that technology has furthered as well as faked the funk, there are other conversations to have with him.

One can always discuss the harmonic relationship he nurtured with the late Kenny Kirkland, a key member of the Black Codes ensemble. Or one can discuss Marsalis’ tonal richness as a trumpeter, why his notes are broad and flugelhorn-full and his phrasing so choral.

Intriguingly there is common ground between Wynton Marsalis and his most fervent detractors, points of convergence amid the divergence. He and the unofficial anti-Wynton Keith Jarrett are both united by their rejection of electric instruments. And they are also united by the fact that they are both classical as well as jazz musicians who like to write sententious articles.

Then again what unites Wynton Marsalis with many musicians is a social conscience, a desire to devote considerable time to educational activities even though his considerable wealth doesn’t make that necessary. From The Plantation To The Penitentiary is explicitly socio-political but like many thought-provoking artists Marsalis eschews the stance of placard bearer. “I don’t look at it so much as protest just awareness music,” says Marsalis who has written lyrics since he was a child. “It’s like that song ‘Find Me’ says, everything is a matter of perspective.

“There’s the perspective of the slave and then there’s the perspective of the slave owner so it’s a matter of opening your eyes and being aware of the many different perspectives.”

Although a cultured polyglot as liable to quote Goya and Yeats as he is Ellington and Mingus, Marsalis is not above straight talking and one of the defining features of his new work is its sheer urgency and anger. Those very feelings have been a major part of the lyrical bedrock of hip-hop. Several years ago the rapper Chuck D told a packed audience at a vibrant lecture in Brixton that the fate of many African-Americans was to “pick electronic cotton on a cyber plantation.” He also voiced clear concern over a consumer culture gone crazy where those with the least – the poor, the blacks, the poor blacks – are targeted the most.

Public Enemy’s mastermind was unwittingly prefiguring ‘Super Capitalism’ or ‘Where Y’All At?’, highlights of From The Plantation, an album whose rhymes and beats were written by emcee Marsalis. “That’s part of that legacy of colonialism,” he says of our hyper materialistic ways.

“Just take everything that you can and then take some more of it… there’s never enough of it. It’s the spirit of taking all the time. The context is trying to retain control of other people’s resources instead of just dealing with them. Just deal with them, pay them! That’s all you gotta do!

“It’s kind of fashionable to jump on Iraq because everybody over here is angry about ii and now we’re all complaining. Bui I’m not specifically talking about that.

“I just mean anywhere where you feel like it’s better for you to lake stuff from somebody than just pay them for it. It costs much less than to just pay them for it. America and Britain is a part of that too. It’s a whole mindset in the world. It’s not even a matter of pointing fingers like it’s outsiders. When I refer to America I consider that to be us. I don’t consider ii to be y’all even though the song is ‘Where Y’all Al?’ I’m a part of America. I’m not separate from America

by Kevin Le Gendre

Source: Jazzwise Magazine