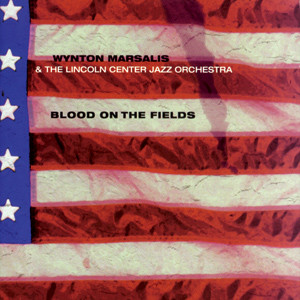

Marsalis Unbound

Following a limited number of concert performances, Wynton Marsalis’s Pulitzer Prize-winning composition “Blood on the Fields” has finally arrived on CD, allowing it the wider audience it deserves.

Marsalis’s first work for jazz orchestra and voices is an often brilliant sonic tapestry that, like the most ambitious extended works of Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus, conjures up a compelling parable.

In this case, the “peculiar institution” of slavery — America’s great sin, as unforgiven as its consequences are unresolved — provides the setting for a personal, universal journey to freedom. But even though this oratorio is set during slavery, its themes are timeless. And though it is deeply informed by race, it is not bound by it. Marsalis recognizes, and at times particularizes, the poisonous legacy of the past yet his message is not about anger or revenge or guilt, but about the redemptive powers of love and community.

To achieve this, Marsalis has for the first time written for voices and has created his own libretto. The voices belong to the exquisite contralto Cassandra Wilson, the gruff tenor Miles Griffith and the venerable Jon Hendricks, one of the progenitors of scat singing. Hendricks, portraying Juba, a wise elder, has several sprightly showcases. But Wilson and Griffith personify the story as Leona and Jesse — she a common girl, he a prince, both ripped from the African soil and transported to a new world of horror and indignity.

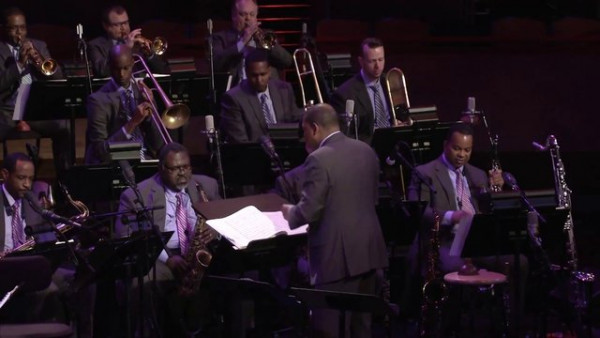

Marsalis also uses the 15-piece Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra as a Greek chorus whose brief narrative recitations introduce 18 of the 21 sections that make up “Blood on the Fields.” There are seven sections that are purely instrumental and others that offer extended instrumental passages.

As its three-hour length might suggest, “Blood on the Fields” is unhurried, but it seldom flags. In part, that is because Marsalis embraces, celebrates and melds the totality of jazz history — from its roots in spirituals, field hollers, blues and ragtime to American popular song and postmodern dissonance — without succumbing to mere chronology. Using the brilliant instrumentalists he has brought together as artistic director of jazz at Lincoln Center, Marsalis creates music that swings, sways and startles, evoking a richness of rhythms and tonal textures. There are striking ensemble voicings that are clearly informed by such past masters as Mingus, Gil Evans and, most obviously, Ellington and Billy Strayhorn.

There’s a bittersweet irony in the last connection. In 1965, Ellington was chosen to be honored by the Pulitzer Prize music panel, but was rejected by conservative bluebloods who refused to honor a quintessentially African American music form. Like much of Ellington’s canon, the score for “Blood on the Fields” on Sony/Columbia includes both meticulously composed sections and others that allow for improvisations on Marsalis’s musical themes.

Previous Pulitzer Prize-winning compositions have been completely scored in the European tradition and entries required both a written score and a recording. “Blood on the Fields” necessitated a rethinking of the criteria. From now on, the requirements will be a score only for the nonimprovisational elements of a work and a recording of an entire work. And where the award once referred to compositions for “larger forms including chamber orchestra, choral, opera, musical theater” — but not for jazz orchestra — the Pulitzer will henceforth be given for “a distinguished musical composition of significant dimension.”

Like “Blood on the Fields.”

The work opens with an aching solo trumpet line (reminiscent of the clarinet wail that begins Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue”) before descending into the cacophonous instrumental blur of “Calling the Indians Out,” which anticipates the litany of “crimes against the human soul far too large for any describing words.” Indeed, it’s the edgy dissonant moans and cries of saxophones, trumpets, trombones and clarinets that underscore the interrupted rhythm of life and anticipate a dislocation that will be both physical and emotional.

“Move Over” introduces Leona and Jesse, who are on a slave ship “that darkly sways beneath the star of democracy” on its journey to New Orleans. Against a queasy, rolling ship’s motion that suggests the numbing horror of the Middle Passage, Jesse clings to hope, but soon succumbs to reality: “I think I hear a drum . . . No, that’s not the sound of my drums . . . That same beat, the same damned beat of iron drums/ no memory./ Stop it./ Stop it . . . demons come to eat me.” Wilson’s deep, lustrous voice evokes a cello-like melancholy, spiraling down into the madness of “Rocking tomb, Blood wet womb/ Many cry, O brown doom, beg to die and do.”

Jesse’s not particularly perceptive: On “You Don’t Hear No Drums,” he’s aloof, self-centered, dismissive of the low-born “common girl.” After all, he’s a prince — and a slave owner! As Griffith shouts defiantly over a funky arrogant strut — “All you hear. The clattering of broken bones and homes . . . echoes of dead voices final screams . . . the mocking cry of past accomplishments” — he clearly doesn’t realize that his and Leona’s tragic common circumstance has eliminated all class and gender distinctions.

The horrors of slavery become more apparent in “The Market Place,” an instrumental tune whose benign Caribbean pulse provokes sharp solos from tenor saxophonist Robert Stewart and baritone saxophonist James Carter, and “Soul for Sale,” where Hendricks-as-Juba adopts the persona of both slave seller and buyer. The latter tune sharply renders the shopping-list banality of the evil trade: “What’cha got to make my corn grow?/ New pipes for my tobacco/ Yes, and let’s see that Negro,” Juba squawks as Leona and Jesse are sold to the same plantation.

That pairing is followed by one of the work’s most mesmerizing and emotionally corrosive sections, the funereal “Plantation Coffle March.” (A coffle is a string of slaves chained together.) It begins with Carter’s baritone saxophone voiced against trombones, bass and tambourine, and when Leona and Jesse sing, the comparative state of their souls is clearly reflected: Wilson’s deliberate, dirgelike verses seems to be spiraling downward, while Griffith’s are defiant and seem to twist upward as he refuses to recognize his changed circumstance.

Much of what comes after addresses Jesse’s rebellions, his episodic escapes and their consequences. “Work Song (Blood on the Fields)” jumps ahead through 14 years of bondage, with Wycliffe Gordon’s trombone heralding a repeated rhythmic figure whose jumpy clatter suggests the numbing tedium of field work. “Blood on the fields/ King cotton grow/ Brown soil yields/ White up above/ Red down below,” Leona moans, as Jesse plans his escape (“Flying High”). Leona also unburdens herself with “Lady’s Lament,” a gorgeous tango-laced ballad that dissolves into a spare, sinuous hand-jive rhythm.

After a religious pairing that contrasts ironic piety (“Oh We Have a Friend in Jesus”) with discomforting truth (the edgy swing and sway of “God Don’t Like Ugly”), Juba reappears to offer the central message of Marsalis’s work in “Juba and a O’Brown Squaw.” Against jubilant New Orleans-style brass-band syncopation, Juba counsels that rather than simply hating his circumstance, Jesse must redirect his energies because “the land that holds you slave is the same that lets you go.”

“Love the land, forgive it for its sin,” Juba says, adding this advice: “If you’re going to get away you must know who you’ll be . . . If no one helps you run then you haven’t got a chance . . . Sing with soul . . . Be sad but sing a happy song.”

In interviews, Marsalis has defined soul as “addressing adversity with elegance. You don’t allow your tragedy to be magnified in the world — you transform your tragedy into something useful that’s optimistic. That’s the whole proposition of soul.”

Such lessons are hard-won, of course.

Jesse escapes again (“Follow the Drinking Gourd”), and his inevitable capture provokes shame in Leona, who in the spare “My Soul Fell Down” yearns for his companionship — until Jesse’s brought back — “dog-bit, chain-burned” — and subjected to “Forty Lashes.” That roiling instrumental by drummer Herlin Riley, alto saxophonist Wess Anderson, clarinetist Victor Goines and pianist Eric Reed captures the pain and anguish of what becomes a cathartic transformation for Jesse (“What a Fool I’ve Been”). That moment, reflected in Mingus-like dissonance and emotional tension, resolves in “Back to Basics,” another instrumental, but one replete with resolve and energized humor evident in exchanges between pairs of trombones, saxophones and trumpets.

Juba’s not through, either. In the scat-laced rhythmic romp “Look and See,” he warns, “Don’t fall in love with the weight of your pain.” And the New Orleans-flavored “Freedom Is in the Trying” underscores the notion that “freedom is no simple thing, but all you need to know/ Freedom’s in the trying, just walk on through the door . . . That’s all you need to know.”

On the mesmerizing “Chant to Call the Indians Out,” the orchestra builds a clap-fueled work song until it gains in depth and power, ending in the plaint “Oh! I sing with soul: Heal this wounded land.”

The work ends with “Due North,” a field holler that points hearts and souls in a new direction.

Digested at a single sitting, “Blood on the Fields” seems to move along faster than its broad scale would suggest. That’s due not only to Marsalis’s compositional acumen — only a few sections drag from a lack of resolution — but to the facility of his compatriots. Cassandra Wilson’s Southern-bred melancholy and Earth-mother resilience are perfect for Leona. Griffith’s tenor reflects the anguish and resolve at the heart of Jesse. And though Hendricks’s showcases are limited, he fills his space with a sage’s brio.

As for the instrumentalists, the section work is so tight and uniformly transcendent that it’s almost unfair to single out the taut, tireless rhythm section — pianist Eric Reed, bassist Reginald Veal and drummer Herlin Riley — or saxophonists Carter, Victor Goines and Wess Anderson, or tuba and trombone virtuoso Wycliffe Gordon. As for Marsalis, who is not only the work’s author but its director, conductor and Juba-like sage, his participation on trumpet is brilliant but necessarily limited by the demands of his other roles. In the end, of course, he’s all over “Blood on the Fields,” the first-ever jazz work accorded a Pulitzer Prize.

For someone who’s 35, that’s remarkable recognition for remarkable achievement.

by Richard Harrington

Source: The Washington Post