Wynton Marsalis Takes a Long Look at Slavery

Wynton Marsalis’s skills have grown as fast as his ambition, and he is the most ambitious younger composer in jazz. On Friday night at Alice Tully Hall, he led the world premiere of his first work for big band, “Blood on the Fields,” a large composition — nearly three hours of music — about a vast topic, slavery. The piece was commissioned by Jazz at Lincoln Center, of which Mr. Marsalis is the artistic director.

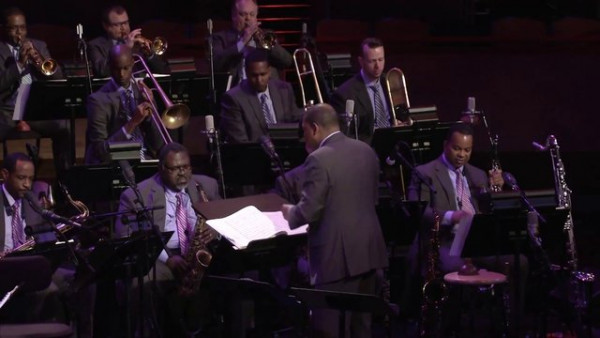

For the new work, Mr. Marsalis not only shifted from his usual septet to a 15-member jazz orchestra; he also worked with text (his own libretto), singers and narrative. But he responded to the change in scale and ensemble with an outpouring of ideas. His music holds on to jazz fundamentals — blues and ballads, swing and Afro-Caribbean rhythms, call-and-response — while abstracting them into fast-mutating collages. With “Blood on the Fields,” he also proves he can write melodies that sound natural for singers.

“Blood on the Fields” follows two captives, Jesse and Leona, from Africa to slavery in America. Jesse (Miles Griffith), an African prince, rebels and repeatedly tries to escape; the more resigned Leona (Cassandra Wilson) provides solace and nurturing. A savvy elder, Juba (Jon Hendricks), guides Jesse toward mental freedom and “soul,” defined as “the giving without want; the sharing of some soothing sweetness.”

It’s not a character study but a parable, one that grows misty at the end with advice like “freedom is no simple thing but all you need to know.” Along the way, Mr. Marsalis creates memorable sonic pictures: bass slides and cascading saxophones for a heaving slave ship, volleys of percussion and wailing horn solos for a flogging, a boogie-based mesh of repeating phrases for the tedious labor of cotton picking. He also lets loose all he knows about the way winds and percussion work together and about jazz history from New Orleans brass bands to abstruse modernism.

The music demands precision, and the big band, built on Mr. Marsalis’s septet, delivered it. Mr. Marsalis cherishes Duke Ellington’s universe of suave saxophones, mocking trombones and brightly assertive trumpets. With Jazz at Lincoln Center, he has crusaded for Ellington’s later suites, Olympian works in which wisps of melody and hints of styles pop into earshot and disappear, finding continuity in the band’s assurance. Those suites are among Mr. Marsalis’s touchstones for “Blood on the Fields,” and he often pushes their intricacies further.

Although Mr. Marsalis regularly denounces avant-garde jazz, he has adopted one technique often used by composers like Henry Threadgill and Muhal Richard Abrams. Like them, he knows that above a swinging beat, a wily composer can get away with nearly anything. Mr. Marsalis’s ensembles bristle with polytonality, dissonance and jagged, jumpy lines and countermelodies, but the rhythm section pushes them along as if they were dance music. The slyly titled “Back to Basics” camouflages unlikely lines within a swing-band rhythm and the laughing inflections of trumpet, trombone and clarinet. “God Don’t Like Ugly,” a waltz, intersperses a straightforward vocal melody with scurrying, discordant tangents of trumpets and saxophones.

Throughout “Blood on the Fields,” Mr. Marsalis adroitly balances such fancy gambits with the vernacular of blues and ballads. He gives the singers melodies that they can hold on to. Mr. Hendricks tossed off his terse, blues-riff melodies, then sprinted through bursts of scat singing that had the other musicians onstage beaming with appreciation. Ms. Wilson’s deep, liquid-amber voice brought melancholy to her long-suffering dirges and a sultry yearning to “Will the Sun Come Up” and to “Lady’s Lament” (a homage to “Lush Life”). Mr. Griffith worked to warm the chromatic turns of his songs.

Like most of Mr. Marsalis’s recent large works, including the remarkable “Citi Movement” (Columbia), “Blood on the Fields” seems to sum up all his previous efforts and move ahead. He comes up with elaborate structures and musicianly abstractions, but also encourages old-fashioned jazz pleasures: snappy riffs, strutting syncopations, repartee between sections, competitive solos and the bedrock of the blues. As the length of “Blood on the Fields” suggests, he is, if anything, too generous.

“Blood on the Fields” has pretentious moments, but they’re brief. Most of its 20 sections are introduced with a line or two — “Reborn in this land of plenty as livestock. Talking work animals.” — recited in unison by the whole band; Mr. Marsalis conducted the speech rhythms. Perhaps the spoken chapter headings were devised knowing that the work would be broadcast live by National Public Radio on Saturday night to inaugurate a weekly series, “Jazz from Lincoln Center.”

“Blood on the Fields” is to be rebroadcast tonight at 8, on WBGO (88.3-FM).

by Jon Pareles

Source: The New York Times