Marsalis Muses On His First Concerto (For, Yes, Violin)

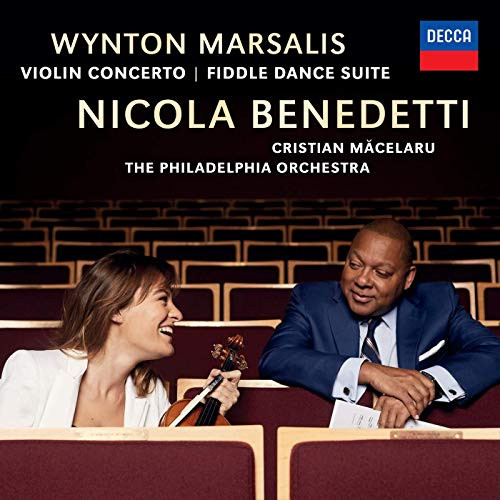

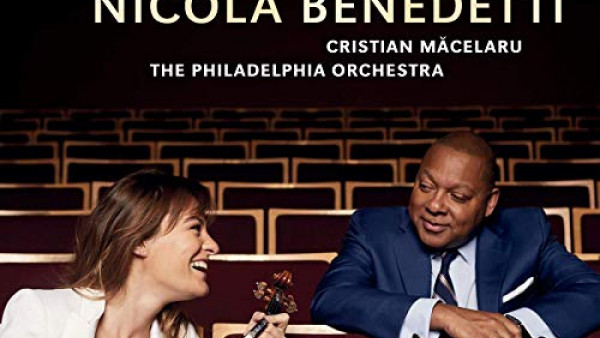

HIGHLAND PARK, Ill. — When jazz musicians venture into the world of classical music, such undertakings often get tagged — sometimes pejoratively — as “crossover” projects. But for renowned trumpeter and composer Wynton Marsalis, the managing and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, working in the classical realm does not mean crossing over to some foreign stylistic territory but rather returning to familiar musical ground, as should be evident when his Concerto in D (for Violin and Orchestra) receives its American premiere July 12 at the Ravinia Festival by violinist Nicola Benedetti, guest conductor Cristian Măcelaru, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

The classical field has been part of Marsalis’ life since the earliest days of his career. At 17, he became the youngest musician admitted to the Tanglewood Music Center (formerly the Berkshire Music Center), the prestigious summer training program in Lenox, Mass., for emerging professional musicians, and he began musical studies at New York’s Juilliard School in 1979. Four years later, he released his first of more than a dozen classical albums, a Grammy Award-winning recording as soloist in the trumpet concertos of Franz Joseph Haydn, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, and Leopold Mozart. His more recent efforts have been compositions, including Blues Symphony and Swing Symphony, which debuted in 2009 and 2010, respectively.

“One of the great gifts that I had from my father and other musicians, who were not prejudiced and close-minded, was the ability to hear (classical) music and to love and respect that body of music,” Marsalis, 54, said in an interview. “That starts with Palestrina and goes up to whoever you want to.”

So when he sat down last year to write his first concerto, the only surprise was the instrument he chose to feature. It might have seemed logical for Marsalis to target the trumpet, but instead he chose the violin. The resulting work received its world premiere in November 2015 by the London Symphony Orchestra and Benedetti. The Scottish violinist will be soloist in just the second performance of the work this week as part of the Chicago Symphony’s annual Ravinia residency.

The roots of the concerto go back 12 years to when Marsalis and Benedetti, now 28, met at the annual international summit of the Academy of Achievement and became friends. Marsalis said the two have much in common, including being southpaws, achieving considerable success in their fields at a young age, and having to deal with the challenges and pressures that come with the attention.

In the intervening years, Marsalis posed various questions to Benedetti about the violin; he incorporated her suggestions into several works. Six or seven years ago, the violinist even made a chart for him with fingerings and other technical information about the instrument. Marsalis does not remember which of the two broached the idea of him writing a concerto for Benedetti, but they quickly and enthusiastically embraced the project. Marsalis got started on the composition in the spring of 2015 and worked intensively on it in June and July.

Among the challenges for Marsalis was adapting the jazz idiom —what he calls “our style of music” — to the symphony orchestra and finding the “natural connections” between the two.

“A really good orchestration is not easy,” he said. “If you are trying to orchestrate swing and rhythms and grooves and you try to do something very different and to make your music sound the way you want it to sound and not some cliché of modern music, it’s even more difficult.”

But, of course, he had plenty of experience to fall back on, starting with the many jazz compositions he had written that set a soloist against a larger ensemble, works that are not called concertos in that realm but function in much the same way. And he has performed an array of famous trumpet concertos, including the Haydn, which he learned when he was 13. “That’s such a great concerto just in terms of the form of it and the function of it,” he said. “And I think my knowledge of concertos and what it is comes from my first encounters with that piece.”

In August 2015, Marsalis scheduled a workshop rehearsal of his violin concerto at the Chautauqua (N.Y.) Institution so that he could hear it and make necessary corrections. Since the work’s premiere in London, he has made additional revisions, including a major reworking of its two cadenzas and modifications to the orchestration. With these changes, the work’s playing time has slightly shrunk from more than 45 minutes to 41 or 42 minutes.

Without prompting, he acknowledged that the piece had received some criticism after its first performance for being too long, but Marsalis shrugged off such complaints. “Everybody writes different kinds of music,” he said. “I write music that is long. That’s what I do. I don’t write two-minute or three-minute pieces. And I don’t feel bad about them being long.”

As might been expected, the concerto is suffused with the sounds of jazz and blues, but it also incorporates an array of other musical genres. “No other work of Marsalis’ seems to reach out so overtly to every aspect of America, not just African-America,” wrote music critic Ivan Hewett in the Telegraph in London.

The piece opens with a lullaby, ends with a section titled “Hootenanny,” and includes circus music along the way. It turns out that Marsalis played in a circus band when he was 15 or 16. “I always use my own language,” he said. “I grew up in New Orleans and played New Orleans hymns, marches, and circus tunes. (I) played classical music. I’m very comfortable with our music, and I don’t try to imitate stuff or be part of any clique. I love jazz — the music and the possibilities of it. I come mainly out of that.”

The work also has some Anglo-Celtic influences, but Marsalis said he did not have to stretch to add those. He sees them as an intrinsic part of the heritage of jazz, noting that fiddlers played in early New Orleans bands and that the Irish jig was a precursor to tap dancing. “When (African-American playwright) August Wilson was dying, he asked me to play at his funeral and he requested that I play ‘Danny Boy’ and learn the words.”

Marsalis is lavish in his praise of Benedetti’s ability to handle the idiomatic and at times almost improvisational quality of the concerto. “Man, she’s great,” he said. “She practices and she’s serious. She’s for real.”

Now that Marsalis has a concerto under his belt, is he ready to tackle another? “I don’t know. I write stuff that is always personal,” he said, noting that he composed Congo Square for Ghanaian drum master Yacub Addy and Griot New York for choreographer Garth Fagan. “If somebody wants to commission me, I’ll do it,” he said. “I do it when I have a certain feeling about people and want to do something.”

by Kyle MacMillan

Source: Classical Voice North America