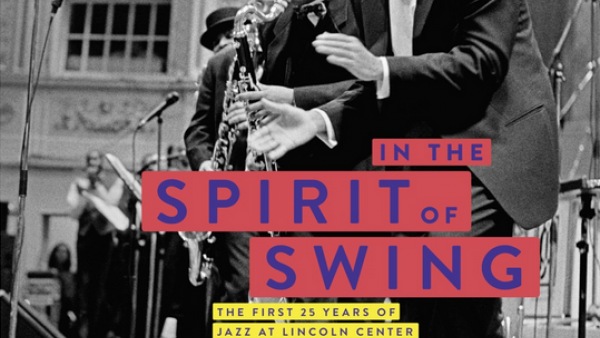

Just One Bishop at High Church of Jazz Purity

Greg Scholl, left, executive director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, with its artistic director, Wynton Marsalis. Credit Robert Caplin for The New York Times

LAST spring, after Wynton Marsalis took over the reins of Jazz at Lincoln Center on a temporary basis because the executive director had resigned, he hinted, as he shook hands with donors at a gala fund-raiser, that he was unhappy with the way the institution had been managed. He likened it to an orchestra without a leader or a musical score.

“I want the way we run to be just like a band runs,” Mr. Marsalis said.

Eight months later, as Jazz at Lincoln Center celebrates its 25th season, Mr. Marsalis has shaken up its management, consolidating his power over the business side, hiring an expert in digital media as the executive director and bringing in two young programmers to shape the concert schedule.

It has always been hard to separate Jazz at Lincoln Center from Wynton Marsalis, the virtuoso trumpet player and composer, who is the closest thing this era has to a jazz superstar on the scale of Duke Ellington. Since helping start the institution, he has been the artistic director and chief evangelist for its mission to promote jazz as high art, building it into the most influential and successful entity of its kind, with a sleek concert hall, well-heeled donors and brimming coffers.

But he has long been a polarizing figure, whose conservative philosophy about what jazz is, and what it is not, has been a divisive force in jazz circles. His detractors say Jazz at Lincoln Center has focused too much on past masters while giving too little attention to innovations in the form since the 1960s. Now Mr. Marsalis has hired programmers who say that, while the organization will maintain its commitment to giants like Ellington and Louis Armstrong, they want to enlarge its tent to include more experimental artists.

What this means for offerings at the institution’s three performance spaces on Columbus Circle remains to be seen. What is clear is that over the last year Mr. Marsalis has expanded his role by revamping the managerial chart, putting himself at the top of the pyramid.

At the same time there has been an exodus of top officials, beyond Adrian Ellis, the executive director who had stabilized the organization’s finances after years of turmoil. Other resignations included Todd Barkan, the veteran jazz impresario who had programmed Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola, and the longtime director of programming, Laura Johnson. Some of these eight departing officials left voluntarily for better jobs, but others were forced to resign.

Mr. Marsalis was circumspect about his motives for the reshuffling. “Institutions evolve,” he said over coffee at a diner on Ninth Avenue before a rehearsal. “People leave, and things change. That’s the nature of institutions.” He added: “Some people were asked to leave. That’s a fact.”

Of his own expanded role Mr. Marsalis said he believed it was better that one person have the final say over both business decisions and artistic choices. “In arts institutions, when a person who is programming doesn’t have any fiscal responsibility or organizational responsibility, it can create a dysfunction, and it does,” he said. “I’m giving you a program to sell, but I’m not responsible whether you sell it or not.”

To lead the business side Mr. Marsalis in June brought in Greg Scholl, 43, a well-regarded executive from the digital music world who was the president and chief executive of Orchard, an online distribution company, from 2003 to 2009, and who ran the online operations for NBC’s television stations. Mr. Scholl said Jazz at Lincoln Center had been too focused on selling tickets to concerts rather than building a global audience for jazz through social media and its Web site.

Mr. Scholl is trying to pull Jazz at Lincoln Center into the digital age. It has begun broadcasting concerts over the Web, and Mr. Scholl said he plans to have every event streamed live at no charge in the near future, with the artists retaining the rights to the recordings. He also started preparing hundreds of recordings from past concerts, so they can be made available to the public online, along with digital copies of Jazz at Lincoln Center’s vast library of scores and solo transcriptions. Plans for a YouTube channel dedicated to live jazz are also in the works.

“Ownership is really a red herring in the modern media age,” Mr. Scholl said. “What really matters is building audiences and having people engaged in what we do.”

He has also begun to build bridges with the owners of local jazz clubs, who in the past have seen Mr. Marsalis’s outfit as insulated from currents in the New York scene, whether avant-garde or traditional. An avid record collector, Mr. Scholl has organized nights on which dozens of Jazz at Lincoln Center employees go to a jazz club in a gesture of support. “We are not a monastery,” he said.

Mr. Marsalis has also overhauled the programming team, bringing in Jason Olaine, 44, who most recently booked the Newport Jazz Festival, and Michael Mwenso, 28, a British vocalist whose last job was running a late-night jam session at Ronnie Scott’s in London. Mr. Olaine has broad tastes, as he demonstrated in his choices of acts for the Newport Jazz Festival and, before that, for Yoshi’s, the San Francisco Bay Area club.

This season at Jazz at Lincoln Center, the first with Mr. Olaine’s input, was again dominated by festivals celebrating the masters — John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, Chick Corea, Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker — as well as a performance of Mr. Marsalis’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1997 composition, “Blood on the Fields.”

Yet Mr. Olaine also sprinkled in a few shows that reflect his more adventurous bent, among them a collaboration between the jazz-fusion guitarist Bill Frisell and Bad Plus, a trio that combines far-ranging jazz with rock and pop hits.

“We want to make these musicians feel they have a home here at Jazz at Lincoln Center too,” Mr. Olaine said. “That’s not only Wynton’s desire going forward, but it’s where I come from musically. I think there is lots of room for lots of different jazz voices under the tent.”

Mr. Olaine said next year’s season would be devoted entirely to contemporary trends in jazz. “There will be new names here, certainly,” he said, “that haven’t played at Jazz at Lincoln Center before.”

That more open spirit is beginning to be felt at Dizzy’s Club on Thursdays and Saturdays, when Mr. Mwenso, a tall Sierra Leone-born baritone, invites young jazz musicians and a few veterans for a late-night jam session that has begun to attract a 20-something crowd. Though many of those who attend play mainstream styles, a few edge toward a fusion with pop and rock, like Eric Lewis, a pianist who does rock-inflected jazz, and Jonathan Batiste, a Louisiana pianist with an eclectic style.

Employees said Mr. Marsalis is a demanding manager, exacting and principled, yet willing at times to bow to opposing views if he thinks his subordinates have expertise he lacks. The buck, however, stops with him.

“He’s demanding and absolutely uncompromising on things that he feels are of fundamental integrity to what we do,” Mr. Scholl said.

For his part Mr. Marsalis likens his management style to the give and take in a jazz combo, what he calls the “nonhierarchical hierarchy of jazz.”

“You can’t get people of certain level if they don’t have autonomy and an outlet for their creativity,” he said. “To understand the jazz world — it’s the opposite of a cult of the personality.”

Yet many in jazz circles say it is Mr. Marsalis’s strong personality that has proved to be instrumental to the organization’s success. A quarter-century after its founding the organization is free of debt and running surpluses, having paid off the $131 million cost of its performance spaces and studios at Columbus Circle.

“Wynton is criticized for his one-mindedness, but his one-mindedness is what makes it all happen,” said Randall Kline, the founder of SFJAZZ, a similar organization in San Francisco.

Mr. Marsalis said that in making programming decisions he would continue to stand by his principles: his core belief that jazz, to be jazz, must be based on swing rhythms with elements of the blues, firmly rooted in black musical traditions. It is the same stance he took when he started Jazz at Lincoln Center with the critic Stanley Crouch in the late 1980s, causing a schism in the jazz world.

Some musicians agreed with him that jazz had become diluted when artists tried fusing it with rock, funk or electronic abstractions. Others saw Mr. Marsalis as an out-of-touch purist who had written off innovators who had blended jazz with pop and experimental music, even beloved figures like Herbie Hancock.

Mr. Marsalis bristles at those complaints. In recent years, he points out, Jazz at Lincoln Center has showcased older free-jazz figures like Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor and has devoted concerts the music of composers like Charles Mingus. He name-checks a list of young artists with a less traditional approach to jazz whom he has showcased, among them Mr. Batiste and the bassist Christian McBride. And he points out he has even done wildly popular, genre-mashing concerts with rock and county musicians: Eric Clapton, Paul Simon and Willie Nelson.

“Our programming has always been broad,” he said.

Still, there is a perception among jazz promoters that Mr. Marsalis has yet to embrace fully a new generation of jazz players at the forefront of reinventing the form, like Vijay Iyer, Robert Glasper, Christian Scott and Esperanza Spalding.

George Wein, the well-known jazz promoter who is a member of the Jazz at Lincoln Center board of directors, said the shake-up was needed to bring in “new blood” like Mr. Olaine, who he said would help the programming reflect today’s trends.

“You need that,” he said. “You can’t stay with the same tradition, not only just with the music, but with the promotion and the marketing of the music.”

by JAMES C. McKINLEY Jr.

Source: The New York Times