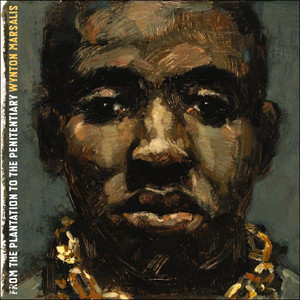

JazzTimes: Wynton Marsalis’ From the Plantation to the Penitentiary

APRIL 2007 – The infuriating thing about Wynton Marsalis is that he is so incredibly talented that you can never simply dismiss him and yet he is so wrong-headed about so many things that you can never wholly embrace him either. Nothing brings this dilemma into sharper focus than his new album, From the Plantation to the Penitentiary.

Marsalis may well be the best technical trumpeter in the history of jazz. It’s always dangerous to claim that someone’s a better trumpeter than Dizzy Gillespie, but from his diamond-hard loud notes to his buttery soft notes, from the nail-gun precision of his fast runs to the bluesy smear of his slow phrases, Marsalis has done everything Gillespie has done in a wider variety of settings. Just listen to his terrific solo—full of staccato bursts, note-bending slides and surprising interval jumps—on the title track of the new album.

He’s also a remarkable composer and arranger. He has no interest in opening new musical territory, but there’s no crime in that, for there’s plenty that can still be mined from the landscape staked out by Ellington, Monk and Mingus. And Marsalis has mined more from that ground than anyone of his generation. On the title tune, for example, he sustains nearly 12 minutes of a midtempo blues by filling it with several melodies, incredibly rich harmonies, push-and-pull rhythms and duets and trios as well as the usual solos and ensemble passages. True, the score could have been written in 1958, but it would have been great music then and it’s great music now.

If From the Plantation to the Penitentiary had been a purely instrumental album, it would have been a triumph of retro-jazz composition and execution. Unfortunately, Marsalis indulges his recurring desire to act as a social commentator, music critic and lyricist, three roles where he is hobbled by his reactionary biases and verbal clumsiness. As a composer, he’s right to pursue jazz classicism, for that fits his talent and inclination. As a music critic, however, he’s wrong to demand that everyone else follow the same path. The same assumption—that everything was better between 1945 and 1965 than it is now—reduces his social commentary to a Ronald Reagan-like nostalgia for an imaginary past. Marsalis sounds downright Republican when he attacks taxes, “modern-day minstrels” and “womb-vanquished dreams.”

It’s bad enough when he expounds these ideas in interviews, essays and TV commentary; it’s worse when he tries to translate those ideas into lyrics. Marsalis shouldn’t write lyrics for the same reason I shouldn’t play the trumpet or the piano: The fundamental lack of competence is impossible to overcome. That’s a problem, because five of the album’s seven numbers are full-fledged songs.

Marsalis’ crimes against the English language are many: awkward rhymes (“slaves” and “trade,” “inside” and “survive”), stilted diction (“We’re running all over the world with a blunderbuss/And the Constitution all but forgot in the fuss”), fractured syntax (“In the name of freedom insane,” “conspiracy theorists and political disconcerts”), mixed metaphors (“reaching for the eyes of a friend”), and empty clichés (“Stick figures chant ghostly names,” “hold me and touch my soul”).

The songwriter’s subject—the truism that many of the same problems that beset America in the era of plantations are still present in today’s era of penitentiaries, just in a different guise—is a worthy one. The bluesy/artsy music suggests that continuity of oppression and resistance in evocative ways, but the lyrics offer nothing new to this much discussed notion.

The title track simply lists familiar examples of the phenomenon. “Find Me” tries to rework the “Oh, say can you see” line from our national anthem into a directive to see our society in a new way, but fails to provide a single memorable visual image. “Love and Broken Hearts” squanders a delightfully romantic melody by daring us to choose between a prostitute’s Vaseline and a Valentine’s candy roses—as if that were really anyone’s dilemma. “Supercapitalism” wastes a jittery, twisting Jon Hendricks-like vocal line on a facile condemnation of greed. Yeah, we get it: Greed is bad.

These four songs are sung by the obviously gifted 21-year-old singer Jennifer Sanon, who is supported by Marsalis and his splendid bandmates: saxophonist Walter Blanding, pianist Dan Nimmer, bassist Carlos Henriquez and drummer Ali Jackson. But on the album’s final track, “Where Y’all At?,” Marsalis takes the mic himself in an ill-advised attempt to beat the rappers at their own game. He suffers from the common misconception that rappers have no skills because they don’t deal with melody. But “flow”—that command of timbre and rhythmic phrasing that make Big Boi, Eminem and Lupe Fiasco such enviable vocalists—is a real skill that Marsalis lacks. Far from flowing, his delivery resembles the most dammed-up river in the history of hydroelectricity.

by Geoffrey Himes

Source: JazzTimes