Blood Brothers

SLAVERY: NOW THAT’S A THEME TO SINK YOUR TEETH INTO. WYNTON MARSALIS THOUGHT SO, and he has – emotionally, mentally, spiritually and musically. With his current “epic oratorio” Blood On The Fields, featuring the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra and singers Miles Griffith, Cassandra Wilson and Jon Hendricks, the intrepid Marsalis has taken a personal look into one of the most ignominious chapters in our nation’s history (see accompanying review).

Marsalis chose to focus on slavery because it’s a subject that “resonates in U.S. history,” he says. “I feel it is the defining issue in our national identity. It still is a major deterrent and stumbling block on our way to really enjoying democracy, enjoying the life of our country and of us enjoying each other.”

The piece originally debuted on April 1, 1994, at Lincoln Center’s Avery Fischer Hall. Marsalis, a self-taught composer and orchestrator (he attended the Juilliard School in 1979-‘80, but studied trumpet, not composition), began to write just two months before the performance. The piece was difficult.

“Trying to get the orchestral voicing, to interweave the words and the music, was hard,” he says. Asked how many hours a day he wrote, he says, “More frantically as it got closer” to deadline. Can he write six or seven hours a day? He laughs softly, “It depends on how late [for the deadline) I am.”

Aiding Marsalis in all stages of the composing was David Berger, former conductor for the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. “He copied the piece,” Marsalis begins. “I would send it to him, he would look at it, and when-ever he saw something he didn’t think would work, he would tell me. I wasn’t very confident at first, but he kept telling me, ‘Man, this stuff looks good.’ He told me that it looked like I was going in the right direction, and that gave me more confidence to write.”

Marsalis also tried the piece out on selected members of his then-touring septet. “Occasionally when we were on the road, he’d call Wessell [Anderson) and me to his room to check out different sounds he had written,” says Victor Goines, the 35-year-old reedman who has known Marsalis since they were both 12 years old in New Orleans. “He’d work in bits and pieces. His way of thinking is always little bit different.”

Also of considerable help were the singers, who suggested slight changes in the libretto. “He would ask me and Cassandra how the lyrics sounded, and we’d tell him,” says Miles Griffith, the 27-year-old Brooklyn-born-and-raised vocalist who was recommended to Marsalis by their mutual friend, Jamal Haynes, and who plays the captured African prince, Jesse. There weren’t many changes, he says, though at one point Marsalis wrote out scatting parts that were nixed. “We just felt that we should do it on our own,” Griffith says.

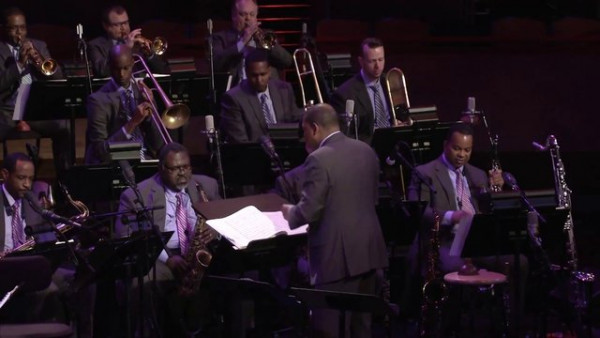

Ten days of rehearsals preceded that April Fool’s debut, and this was demanding work, according to all the musicians DownBeat talked to. “Wynton’s music is always complex,” says Goines, who has been performing in Marsalis-led outfits since 1993. “He ends up writing what he hears, and requires you to figure out how to play it. But conceptually, once you understand this story, it makes everything easier.

“Before I started rehearsing this, I thought I read pretty well,” says St. Louis-based trumpeter Russell Gunn, whose first appearance with Marsalis was the debut of Blood. “l was shocked, like some of the others, when I saw how difficult the music was. Lot of syncopation, long rests, technically demanding. He writes stuff that nobody can play, and then they have to learn it. The real challenges were first to deal with all these time signatures, and then to put emotion into it. That was a bigger challenge than playing the notes.”

Drummer Herlin Riley, 40, a Marsalis associate for almost a decade, talked about the way Marsalis allowed his musicians to personalize this piece. “He mostly writes with people who have worked with him, and he knows their sounds,” says Riley, another New Orleans native and resident. “Like on this piece, he gave me a guide – the music that’s on the paper – but he didn’t write out specific rhythms. He lets me come up with my own parts, which is his standard way of working.”

Marsalis listened to Blood On The Fields a lot prior to the current tour, especially in the mixing of the CD. He says he didn’t really get to hear it at the 1994 premiere. “I had too much to do, too much to concentrate on.” Asked now if he’s pleased with it. he says, “I don’t know. It’s just music. It’s hard to describe what my relationship is to my music. I don’t sit around and listen to any of my albums. I work on the music for the recording, then work on it when I go out to tour and try and play it. Then I go on to the next project.”

The players’ general response to the recording is that it went well. But what’s got them really excited is the current tour, and the series of performances of what they say is the leader’s most important work. Night after night, in places like Los Angeles, San Francisco, Boston, Washington, D.C. and St. Louis (and later spots in Europe), the piece keeps changing, offering new developments, challenges, rewards.

“It’s becoming more alive,” says Riley the day after the ensemble performed in St. Louis. “Each night, we seem to find little nuances to make it unique. And as the music becomes familiar, we internalize it, make it our own.”

“As I get more comfortable, a lot of things are changing,” says Griffith. “Cassandra [who plays the African commoner, Leona, who is captured along with Jesse) and I are really getting into the lyrics. On Blood On The Fields, we’re getting into the actual feeling of the work. And when I sing ‘Oh, What A Fool I’ve Been.’ I sense that this is really the way Jesse feels.”

“The piece unfolds every day because people keep trying something different.” says Goines. “I’ll always play different cadenzas, I might try to hum or scream through the instrument. Then there’s the bass-clarinet duo which we call the ‘heartbeat,’ where Gideon and I play together.”

This piece, delivered in the middle and at the end of the concert, has become the ensemble’s own private mini-concert. Goines and Gideon Feldstein play as the rest of the band leaves the stage. chanting, ‘Oh, Lord.’ Finally, the two clarinetists depart.

But backstage. the “heartbeat” continues. “Sometimes, we’ll go on for 15 minutes, chanting and singing and clapping like a jam session,” says Riley. “Sometimes, we’ll form a circle and dance and make up lyrics and sing. That’s the spirit and fellowship that goes on backstage.”

The humor that Marsalis has injected into the libretto of Blood gets varying reactions from some of the players. It’s completely apropos, says drummer Riley. “The work deals with the blues,” he says. “And the blues is still optimistic. Life can’t be all blue; something has to lighten up.”

Gunn has mixed feelings about the same subject. “First, I don’t know what people are thinking when they laugh at this,” he says. “I know from my own experience that laughter can be the best way to deal with things, relieve tension, particularly if you are black. But some of the words here are funny. When Wynton writes that the ‘massa’ wants his slaves to worship a merciful and just God, that is funny, because people do think that way. I have to laugh when I think about how ignorant that is.”

Each of the players DownBeat spoke with had at least one highlight – general or specific, either of their own doing, or another’s – that they found to be a delight.

Griffith recalls a hot night of scatting in Iowa City, Iowa. “That was the first time that I scatted (at length on the lour).” he says. “Usually I got one chorus, but that night, Wynton signaled me, and I couldn’t believe it. I said, ‘OK.’ That night was really tight, and the people responded, cheering after I scatted.”

Gunn, who plays several fiery solos, also had a fondness for scatting – by that master of the form, Hendricks – and for his section-mate Printup’s improvisations as well. “I always take the most pleasure in checking out Jon’s scat solos,” Gunn says. “And Marcus, I think he has the best sense of melody since Booker Little.”

“It has opened up my whole view of the clarinet,” says Goines. “I have been playing it for 27 years, but before Wynton Marsalis, I considered mysel a tenor saxophonist”

Drummer Riley had a personal spotlight from the St. Louis show he wanted to impart. “On ‘Forty Lashes’ (where Jesse is punished for attempting to escape; he finally does, with Leona, at the work’s end], I played a good one. It just felt right for me,” he says.

“Here I have to play within a specific theme, that of the guy who administers the ass-whipping. I try to go with tones, as opposed to just playing a drum solo. I ended it by holding the ride cymbal, hitting I and then choking the sound, as if I were an angry parent spanking a child. I said to it, said out loud, ‘Didn’t I tell you not to try to get away?’ Last night, that just came out.”

Again, while these musicians regaled Marsalis’ Blood On The Fields as monumental, Gunn stressed the emotion in the work: “This piece touches me. Who I wouldn’t it touch? I always found it disturbing that people wouldn’t put any energy into addressing this issue, and I resent the fact that that it’s downplayed in history. This is a story about two people, but the number that slavery touched is immeasurable.”

by Zan Stewart

Source: DownBeat Magazine