Let Freedom Swing

From coast to coast, newspapers trumpeted the same remarkable tune: A jazz artist had won a prestigious award hitherto given only to classical musicians.

“Marsalis swings a Pulitzer,” noted USA Today, evoking the jazz idiom with its choice of verb.

“Wynton Marsalis captures music honors; first jazz artist to do so,” said the Los Angeles Times.

But the real significance of Marsalis’ award, presented for his epic vocal-orchestral suite “Blood on the Fields,” runs deeper than that. By awarding the prize to jazz trumpeter-bandleader Marsalis, the Pulitzer board gave the distinctly American art of jazz improvisation a degree of recognition and honor it never had received.

From 1943 (when William Schuman won for his “Secular Cantata No. 2, A Free Song”) to 1996 (when George Walker won for “Lilacs”), the Pulitzer Prize in Music had gone to works in which every note had been put on paper by the composer, in the tradition of most European classical music.

Look at the score to “Blood on the Fields,” however, and you will see vast stretches of white space in which the three vocalists, instrumental soloists and jazz orchestra riff freely on Marsalis’ musical themes.

That feature distinguished “Blood on the Fields” from virtually all the entries jurors heard when they met secretly last month in New York to pick three finalists from 80-plus contestants (the Pulitzer board chooses the winner, typically taking into account the jury’s recommendation).

By inviting two listeners associated with jazz (Modern Jazz Quartet pianist-composer John Lewis and this writer) to sit on the jury, the Pulitzer board clearly showed some interest in expanding the range of music to be considered for the award. The other jurors were three winners of music Pulitzers: John Harbison, Joseph Schwantner and jury chairman Robert Ward.

From the outset, it was clear that “Blood on the Fields” raised two critical questions about the nature of American music: What is the value of improvisation, and can it yield genuine masterworks?

To a jazz devotee, the answer to those questions would seem obvious. Louis Armstrong’s sublime trumpet solos in “West End Blues” and “Weather Bird,” the Benny Goodman Orchestra’s stunning “head arrangement” (unwritten) of “Sing, Sing, Sing,” Miles Davis’ haunting album “Kind of Blue”—all were conceived with the barest bones of a score. More important, Armstrong’s glorious melodic flights, Goodman’s thrilling ensemble passages and Davis’ hushed poetry were created specifically through the art of improvisation. No composer sitting in his garrett could have dreamed up such inspired final products.

Improvisation also has played a role in classical music. But although baroque composers leading up to J.S. Bach typically improvised solo and ensemble pieces, and although pieces by Chopin and Liszt suggest the improvisations they routinely played at the piano in European salons, the art of improvisation has all but dried up in 20th Century classical music. With the exception of church musicians, who still improvise organ preludes and the like on Sunday mornings, classical music has become a writer’s art.

The issue is crucial, because roughly three decades ago a furor erupted when the Pulitzer board declined to give Duke Ellington a special citation recommended by the jury in 1965.

When the full Pulitzer committee turned down their recommendation, wrote Ellington in his memoir, “Music is My Mistress,” jurors Winthrop Sargeant and Ronald Eyer resigned.

“Since I am not too chronically masochistic, I found no pleasure in all the suffering that was being endured,” Ellington continued. “I realized that it could have been most distressing and distracting as I tried to qualify my first reaction: `Fate is being very kind to me; Fate doesn’t want me to be too famous too young.’ “ Ellington was 66 at the time.

If any doubt remained that such comments dripped with irony, it was erased by the composer’s remarks to writer Nat Hentoff, recorded in a 1965 New York Times magazine article titled “This Cat Needs No Pulitzer Prize”:

“ `What else could I have said?’ the Duke asked rhetorically. `I’m hardly surprised that my kind of music is still without, let us say, official honor at home. Most Americans still take it for granted that European music—classical music, if you will—is the only really respectable kind. I remember, for example, that when Franklin Roosevelt died, practically no American music was played on the air in tribute to him . . . by and large, then as now, jazz was like the kind of man you wouldn’t want your daughter to associate with.”

The anger over the committee’s rebuke simmered for years.

“The Pulitzer rejection of Ellington,” wrote John Edward Hasse in his biography “Beyond Category: The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington,” “was, as cultural critic Jonathan Yardley has observed, `a confession, however unwitting, of the cultural establishment’s hostility to the new and the different and the unsanctioned. . . . (Ellington) put on a brave front, but he more than anyone else knew the true value of his music and he badly, if not desperately, wanted it accepted for what it was: the great American music, the true voice of his country, a total body of work that was neither jazz nor classical but something that drew strength from both and emerged, triumphantly, sui generis.’ “

In Marsalis’ “Blood on the Fields,” the 1997 jury heard a work that similarly drew on both jazz and classical traditions and therefore represented a broad spectrum of American musical tradition. By alternating exuberant improvised passages with meticulously composed sections, by juxtaposing high-flying instrumental and vocal solos with brilliantly conceived orchestral writing, Marsalis in effect picked up where Ellington had left off (with a few references along the way to music of Charles Mingus).

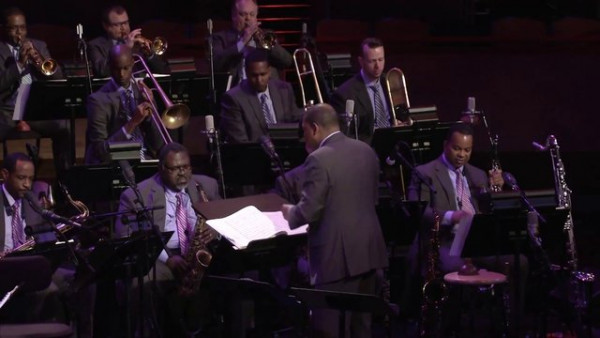

To hear (via tape) Marsalis’ radiant trumpet lines, Cassandra Wilson’s throaty vocal solos, Jon Hendricks’ nimble scat passages, the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra’s resplendent chords and the rhythm section’s pervasive swing backbeat was to savor a major composition that could not have been created without improvisation. Further, “Blood on the Fields” evoked many sprawling jazz pieces that Marsalis and his sidemen have invented over the last decade, from the hypnotic “Majesty of the Blues” (1989) to the three-CD “Soul Gestures in Southern Blue” (1991) to the evocative “In This House/On This Morning” (1994).

Perhaps it was not so surprising, then, that “Blood on the Fields” emerged as the jury’s top choice for the Pulitzer, with John Musto’s lyric “Dove Sta Amore” and Stanislaw Skrowaczewski’s “Passacaglia Immaginaria” following.

In choosing Marsalis’ “Blood on the Fields,” the Pulitzer board for the first time had swung the gates open to jazz and the improvised, oral tradition it implies. If “Blood on the Fields” could win, then why not a scoreless jazz recording on the order of Davis’ “Kind of Blue,” or a thoroughly improvised work, or a sublime group of American popular songs?

The Pulitzer board, in fact, took the gesture a step further, changing the definition and entry requirements for next year’s awards.

While the previous definition awards the prize “for distinguished musical composition by an American in any of the larger forms including chamber, orchestra, choral, opera, song, dance, or other forms of musical theater,” the new text obliterates specific genres, instead giving the award simply “for distinguished musical composition of significant dimension.”

And while the previous instructions required that “all entries should include … a score or manuscript and a recording of the work,” the new instructions ask simply for “a score of the non-improvisational elements of the work and a recording of the entire work.” Explicitly, improvisation is now an accepted part of the Pulitzers.

Whatever happens from here, it would seem there’s no turning back. By giving “Blood on the Fields” a prize widely considered “America’s most prestigious musical honor,” as Hasse termed it, the Pulitzer board has begun to acknowledge an entire world of music outside the realm of the symphony hall.

As the 20th Century approaches its end, the development comes not a moment too soon.

by Howard Reich

Source: Chicago Tribune