A Latin Musician Translates a Meeting of Cultures

The reality that jazz and Afro-Latin music have been mixed for a century can sometimes lead to the myth that a musician trained in one tradition is effectively trained in the other, and that fluency runs both ways at all times, in all places.

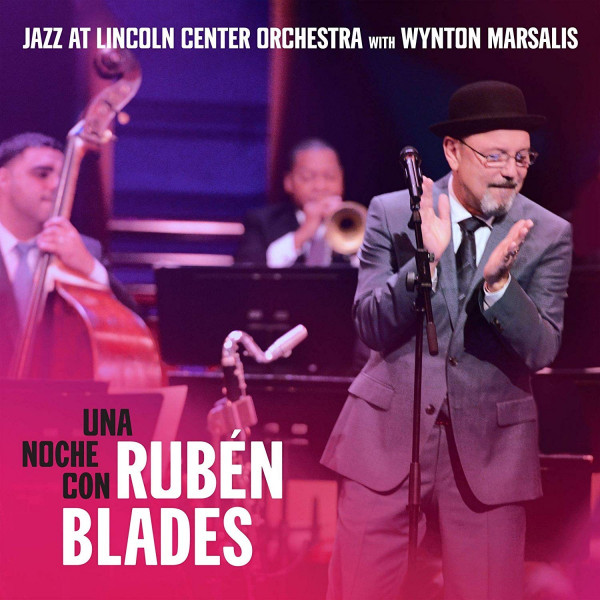

And so you might have looked at an advertisement for the Panamanian singer Rubén Blades collaborating with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, as he is doing through Saturday night at the Rose Theater, and thought, sure, Latin jazz.

Not really, though. What they’re doing isn’t a glib middle ground. It’s a jazz band playing Afro-Latin dance music with authority, which it has taught itself to do over the years, and Mr. Blades gamely singing American standards jazz-style, which he isn’t known for; sometimes, it’s both in the same song.

The new arrangements are by the orchestra’s bassist, Carlos Henriquez. They alternate, and sometimes fuse, clave and swing rhythm, cleverly demonstrating the intersection of traditions. (Three percussionists augmented the band — Marc Quiñones, Bobby Allende and Carlos Padron — as well as the singer Eddie Rosado.) This is all the sort of thing a singer like Mr. Blades — not that there are many like him — would be more likely to try in a recording studio than in a concert without his regular band, a situation in which so much can go wrong. And so even when Thursday’s concert wasn’t entirely hitting where it aimed, you were always watching two virtues: novelty and risk.

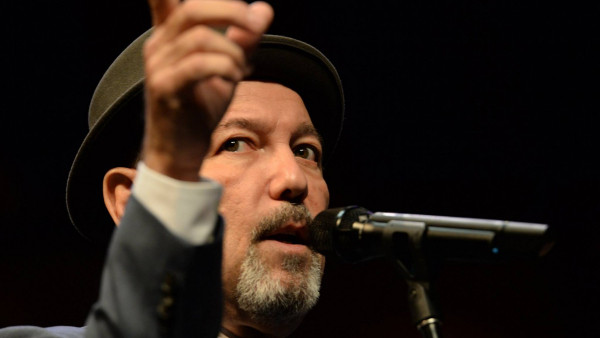

Mr. Blades, 66, may be best known for the progressive New York salsa records he made at the start of his career in the late ’70s, singing provocative lyrics about power relationships and social realities over Willie Colón’s arrangements. Though he’s a strong and resourceful singer, his endeavor is a literary one as much as anything else. He’s working with not only regional traditions of rhythm and sound, but also with global traditions of narrative and politics.

He’s been as a statesman, too, serving as his country’s minister of tourism. On his website this year, he announced that his 2015-16 tour would be his last round of salsa-based performing. After that he plans to work with a small group exploring a “musical fusion,” and to return to political life in Panama. It’s clear enough that music, per se, doesn’t define him.

But storytelling does, to a greater extent, and therefore language, too. On Thursday he seemed most comfortable in songs that had a lot to say, that kept developing a thought or a metaphor; these were typically his own, and sung in Spanish. If there was a peak moment of audience joy, it came during “Pedro Navaja,” his hit from 1978, a story of a petty criminal trying to rob a prostitute, inspired by Bobby Darin’s version of “Mack the Knife.” The crowd sang it all with him, which helped, but Mr. Blades’s voice fully inhabited the song: His words and phrasing expanded to the end of every long breath.

Given his vocal range and his ability to mimic — he imitated Sammy Davis Jr.’s speech patterns a few times on Thursday — he could probably put on a decent imitation of Frank Sinatra. He didn’t do that; he found his own way, taking the job seriously, and hitting some bumps. In songs like “Too Close for Comfort,” “Fever” (sung in a duet with his wife, Luba Mason) and “They Can’t Take That Away From Me,” as well as “Don’t Like Goodbyes,” by Harold Arlen and Truman Capote, he shut down some words a bit early and over-invested certain phrases with vibrato; it was a tentative and regimented kind of singing that made you too aware of meter.

Mr. Blades is loose and personable on stage. But it was fascinating how he could sometimes seem limited by the literary concision of the songs he chose, in which a line or a stanza stands autonomously, with its own meaning, without flowing toward the next thought.

It’s not easy to put on a concert like this: It takes preparation and momentum. Mr. Henriquez’s arrangements delivered consistently. The pianist Dan Nimmer fit the songs’ changing requirements, and Wynton Marsalis’s extravagant trumpet playing in “Ban Ban Quere” did exactly the right thing: It jump-started a complicated experiment. But for the encore, Mr. Blades’s song “Patria,” a severely reduced version of the band came out to back Mr. Blades: just the percussionists, with Mr. Henriquez on bass and Mr. Marsalis playing soft improvised accompaniment. It was simple and radically beautiful. It also suggested that there could be a whole other kind of concert to do.

by Ben Ratliff

Source: The New York Times

Comments

INDEED!!!!!!!

MTSCR on Dec 3rd, 2014 at 4:58pm

I attended the concert on Friday at the Lincoln Center and from now on will be referring to Mr. Marsalis as “Don Wynton”. Don is an honorary title of respect in Spanish and Don Wynton earned it with his interpretation and improvisation in Ban Ban Quera and Patria. His interpretation of Patria was the best solo improvisation that I have ever heard. I am sure that Don Wynton has Puerto Rican blood flowing thru his veins :)

Alberto Roldan on Nov 19th, 2014 at 8:48am