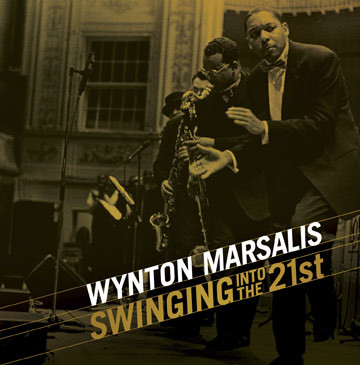

Swinging into the 21st (BOX SET)

Swinging into the 21st” is the name that Wynton Marsalis gave to an extraordinary series of 9 albums he released between 1999 and 2000 on Columbia Records and Sony Classical. In honor of Wynton’s 50th birthday, those nine albums (along with the two CD masterwork All Rise), are presented here as a box set for the first time. Each album in Swinging into the 21st features a different ensemble and style of music. From chamber music to studio and live dates with his septet, jazz and blues tributes, film music, scores for ballet, modern classical and orchestral works, to some bonafide swing, Swinging Into the 21st explores Wynton’s musical universe.

Album Info

| Ensemble | Multiple Ensembles |

|---|---|

| Release Date | October 18th, 2011 |

| Record Label | Sony/Legacy |

| Catalogue Number | 88697944282 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| CD 1: A Fiddler’s Tale – view album | ||

| CD 2: Standard Time, Vol. 4: Marsalis Plays Monk – view album | ||

| CD 3: At The Octoroon Balls – view album | ||

| CD 4: Big Train – view album | ||

| CD 5: Sweet Release & Ghost Story – view album | ||

| CD 6: Standard Time, Vol. 6: Mr. Jelly Lord – view album | ||

| CD 7: Reeltime – view album | ||

| CD 8: Selections from The Village Vanguard Box – view album | ||

| CD 9: The Marciac Suite – view album | ||

| CD 10: All Rise (2 CD set) – view album | ||

Liner Notes

1999 was a very important year in my development. I had been recording for CBS Records and Sony Music for almost 20 years. This relationship allowed for the unprecedented release of 9 recordings. Don Ienner, then president of the label, agreed to support this volume of artistic production despite its economic risk. I viewed his support as recognition of and respect for my contribution to the label and my unwavering dedication to the art of jazz and to music. We called it Swinging into the 21st and it was an optimistic statement on the upcoming century. I was more than fortunate to have Gabrielle Armand as project manager. She wrote the overall plan and release schedule, and oversaw the execution of it with the intensity of a mother. I owe these releases to her tenacity and belief. That entire year, from January 1st to the performance of All Rise with the New York Philharmonic on December 29th, I worked every day from 5 in the morning until 1 or 2 the next morning. I was music, music, music.

Each release featured a different ensemble and style of music, and a unique set of musical challenges. The one unifying factor was jazz, which is the foundation of all that I do and hope to do. A Fiddler’s Tale, a collaboration with The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, was based on Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du Soldat, a piece I have loved since first hearing it as a 15 year old. I used the same ensemble: 2 brass, 2 woodwind, 2 strings, percussion and narrator. This composition demonstrates the kinship between Stravinsky’s harmonic and rhythmic language and the language of modern jazz with a New Orleans accent. Stanley Crouch’s story was treated to a lavish reading by the masterful André De Shields who loved to say, “It’s easy to do with great material.” I enjoyed playing next to bassoonist Milan Turkovic, a genius and a gentleman, and Edgar Meyer, David Shifrin, David Taylor, Ida Kavafian and Stefon Harris.

They all play with such feeling and accuracy. Next was a recording of Monk’s music that featured the septet with Wess and Herlin and Veal and Vic, Cone and Reed. We were a family and played an expansive range of music with intensity, all over the world. Each Monk tune IS a world. We arranged Monk’s compositions to accentuate the musical propositions specific to that tune. A good example is Evidence, which uses the syncopation of broken silences to feature the always inventive Herlin Riley. At the Octoroon Balls is a string quartet written for the fabulous Orion String Quartet. I loved working with them: Danny and Todd and Steve and Tim. When we were recording, if I said, “That was a good take,” they would say, “Hold us to the highest standard … the highest standard!” Big Train was written for the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra and was recorded in a day. We were joined by Doug Wamble on guitar. I wrote this for my son Jasper, who absolutely loved trains. We were separated by a whole continent (he lived in LA; I in NY), but I figured he could hear this and know I loved him, especially The Caboose which is a lullaby. The band gave so much to make this recording. They always do. Westray and Joe and Rodney and Farid and all the cats.

In August, we released Sweet Release and Ghost Story, two ballets with totally different choreographers: Judith Jamison with the world famous Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and Zhongmei Li with her newly established Zhongmei Dance Company. Judith wanted something thick and boisterous—a party. Zhongmei wanted a spare and almost minimal, wispy composition. I always write ballets to the choreographer’s specifications. I like to work for them. Mr. Jelly Lord was inspired by a very successful concert we played at Jazz at Lincoln Center in 1989. A decade later, in January of ’99 we brought some of our New Orleans brethren to New York to record Jelly’s music. We believe ALL Jazz is modern and in that spirit, Jelly Roll becomes a jumping off point for the improvisations that we play on any style.

Every December we played at the Village Vanguard. The club would be packed until 4 or 5 in the morning. Our fans were overwhelmingly supportive and we responded with intense emotional performances. The selections from our 7 CD box set (Live at the Village VANGUARD) capture the feeling and intangible essences of that experience. Many of the greatest jazz musicians came to check out the band in that period —-Lionel Hampton, Clark Terry, Milt Jackson, Sweets Edison, Elvin Jones and others. The Marciac Suite was my gift to the village of Marciac, France; a place of soul, down-home hospitality, great cuisine, and community. The septet enlivens this portrait of the village at Jazz Festival time. I have attended the Festival for over twenty years straight and love it with increasing intensity. There was a big storm the night this piece was to have premiered. We played it the next day in the village square which was overflowing with people. The closing section, Sunflowers, is my testament to the optimism which allows jazz to thrive in this tiny village in the southwest of France. When we start clapping that 5/4 rhythm, the people know what time it is: early August.

Finally, All Rise, which was not a part of the original release schedule, took literally 5 months of 20 hour days to compose. I was hearing so much music, my ears actually became hot and my inner ear was ringing and burning for the entire last month. A team of copyists and the professor of music, James Oliverio, were worn out trying to realize it. We had a sign in the library of my apartment: “The Last Great Masterpiece of the 20th Century.” Of course it was a joke, but by the time we hit the Christmas Holidays of 1999 (which Victor Goines sacrificed to copy the jazz orchestra parts), we had altered the sign to say “The Late Great Masterpiece,” then “The Last Late Masterpiece,” and finally, “The Last Late Piece of the 20th Century.” And it was. This recording comes from a session with the Los Angeles Philharmonic immediately after the attacks of 9/11. Just getting people to the session required our road managers to drive halfway around the country with no rest. And they did.

So much of this music is made possible by people doing extraordinary things on and off the bandstand. I am always humbled and grateful for all the many, many acts of selflessness and sacrifice that have allowed my music to flourish in a culture that is somewhat hostile to art or seriousness of any kind. I know it is due to a lack of quality education, but it still hurts. We have so much potential. I want to thank all of my supporters and colleagues who have given so much to me and my music. Even in the last days of 1999, All Rise was late arriving to the New York Philharmonic. It was very difficult to play. Some of the percussion parts were given to Chris Lamb the day of the concert. The Philharmonic and Maestro Masur had worked so hard to make a good performance. Dr. Nathan Carter and the Morgan State University Choir had gone far above the call of duty, and the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra had already killed themselves to make it successful.

But there was just not enough time. It didn’t sound good… at all. Two hundred people on the stage of Avery Fisher Hall and from where I sat, near the middle, it was pure cacophony — most of the time. The audience did their best, but I felt like I had committed a 1 hour and 50 minute crime on the musicians and the public. Following the performance and after everyone had gone, I went back into the hall. I often do that after concerts wherever we may be. I was totally deflated. I thought about how so many people had given so much to put that concert on, and how much we all sacrifice to lift each other’s spirits with music. I looked around the empty hall and said the prayer I said every night of 1999 without fail, “Thank You Lord.” Thank You.

WYNTON MARSALIS

June 2011

Personnel

- Wycliffe Gordon – trombone

- Wess “Warmdaddy” Anderson – alto sax, sopranino sax

- Victor Goines – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet, bass clarinet

- Todd Williams – tenor sax, soprano sax

- Herlin Riley – drums, tambourine

- Ben Wolfe – bass

- Marcus Roberts – piano

- Reginald Veal – bass

- Cyrus Chestnut – piano

- Farid Barron – piano

- Eric Reed – piano

- Rodney Whitaker – bass

- Walter Blanding – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet

- Ron Westray – trombone

- Joe Temperley – baritone sax, bass clarinet

- Paul Smith Singers – vocals

- Esa-Pekka Salonen – conductor

- Morgan State Choir – vocals

- Ted Nash – alto sax, soprano sax, clarinet, flute, piccolo

- Vincent Gardner – trombone

- Ryan Kisor – trumpet

- Marcus Printup – trumpet

- Seneca Black – trumpet

- Jason Marsalis – drums

- Dr. Michael White – clarinet

- Sherman Irby – alto sax, soprano sax, clarinet, flute

- Stephen Riley – tenor sax

- Gideon Feldstein – baritone sax, bass clarinet

- Roger Ingram – trumpet

- Russell Gunn – trumpet

- Jamil Sharif – trumpet

- Wayne Goodman – trombone

- Bob Trowers – trombone

- Pernell Saturnino – conga, latin percussion

- Jaz Sawyer – drums

- Stefon Harris – vibraphone

- Eric Lewis – piano

- Daniel Phillips – violin

- Todd Phillips – violin

- Steven Tenenbom – viola

- Timothy Eddy – cello

- David Shifrin – clarinet

- Milan Turkovic – bassoon

- David Taylor – trombone

- Ida Kavafian – violin

- Edgar Meyer – bass

- Danilo Perez – piano

- Lucien Barbarin – trombone

- Harry Connick, Jr. – piano, vocals