Wynton Marsalis Raises a Joyful Noise

When Wynton Marsalis, the 30-year-old trumpeter and most celebrated jazz musician of his generation, hits the stage at Lincoln Center on Wednesday night, he’ll be playing in a style that, for the most part, can’t be heard on his recordings. The audience’s unfamiliarity won’t be a new experience for Mr. Marsalis. Since 1989, his music has taken a radical new form that has primarily been heard only in clubs and in concerts. Mr. Marsalis has been moving so fast that his recordings haven’t been able to keep up with him. At least until the release of “Blue Interlude” last week, which includes a 45-minute composition of the same name.

Three years ago, Mr. Marsalis expanded his group to a septet, and since then he has been producing long works that take advantage of the group’s size. The pieces resound with echoes of jazz’s masters: Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Charles Mingus.

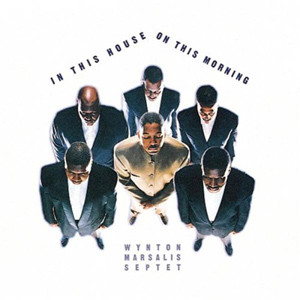

On Wednesday, as part of Lincoln Center’s jazz program, Mr. Marsalis will present his newest extended work, “In This House, on This Morning.” He was commissioned by Lincoln Center to compose the piece, roughly an hour long, especially for the event. Mr. Marsalis says the composition follows the contours of a church service. Like “Blue Interlude,” which will also be performed, the new piece has programmatic elements, with various instruments calling out different parts of the service.

“Each of the 12 sections addresses some specific aspect of the service, along with the spiritual realization that comes about in church,” Mr. Marsalis said recently in an interview from a hotel room in Emeryville, Calif., where, after a concert, he was trying to trim a half hour from the new work. He sounded tired and admitted that the preparation of a major effort, regular performing (Mr. Marsalis plays more than 200 shows a year) and travel were wearing him down.

“ ‘In This House, on This Morning’ addresses the emotional life of a church service,” he continued. “I’ve always been interested in the spiritual experience, because there’s power and substance in the spiritual search. This piece isn’t about a specific religion. It is about the desire to know a God.”

For the composition, Mr. Marsalis says he has taken on a theme that many of his heroes — Ellington, Coltrane, Bach — have wrangled with during their careers: the life of the spirit and its relationship to music and to the religious service. Mr. Marsalis says that the music is keyed to a precisely imagined narrative. The congregation comes into the church, and by the end of the service, it walks out, cleansed by the intensity of the experience. The piece features the call-and-response sections, with shouts and hymns, as well as preachers preaching and bells ringing.

“Using longer forms gives me a chance to deal with development and give everybody in the band room to breath,” Mr. Marsalis said. “It gives you the chance to express different things when you’re not tied to a standard form. The short form, like a song, is great, but it’s somewhere in between a novel and a poem. So it’s challenging to make a long piece coherent, to make it work and to find a way to integrate real group improvisation.”

And if “In This House, on This Morning” bears any resemblance to the long compositions Mr. Marsalis has been playing in New York recently — both “Blue Interlude” and the music for Garth Fagan’s dance company at the Brooklyn Academy of Music — it will represent a dramatic reappraisal of jazz. Mr. Marsalis adheres to a theory of jazz history rooted in an interpretation of its most important practitioners. In his extended works, the harmonic sensibility of McCoy Tyner’s piano and Coltrane’s saxophone, open and oceanic, merges with Mingus’s fierce polyphony. Mr. Marsalis’s trumpet improvisations ramble freely, quoting from Armstrong, Davis and Coltrane; at times, Mr. Marsalis’s writing takes on the pungent bluesiness of Ellington, flashing the bright puffs of color that he specialized in in the last 20 years of his life.

Riffs pop up, tempos change, either abruptly or gradually, and Mr. Marsalis keeps improvisations short, pairing up instrumentalists or changing textures behind soloists. His longer works are virtuoso performances of arranging and composing, with only moments of democracy. Mr. Marsalis is firmly in command.

“People like variety; they get tired of hearing the same form,” he said. “Most of the things I do come from talking to the audience out there. That makes me rethink what I’m doing. We play so many gigs, and so many people come back and talk to us, a car mechanic, a woman who has a printing business or a regular cat; everybody has an opinion and I try and listen to them. Usually they complain about having a bass solo on every song.”

Lorraine Gordon, the owner of the Village Vanguard, the New York jazz club where Mr. Marsalis has played since he was in his early 20’s, has seen Mr. Marsalis’s development as a composer. “It all has to do with his vision of education,” she said. “The sounds he gets range over the history of jazz; he seems to be saying that you have to look back to go forward. He understands how to modernize the music but not lose its value. And the beauty of his trumpet tone and his improvisations bring people along. The bigger band has allowed him the freedom to experiment with the history, to really go into it.”

If “In This House, on This Morning” reaches the complexity promised by Mr. Marsalis’s description, it will also be immensely difficult music. For all the echoes and borrowings, his longer pieces do not have any frame of reference. They are not like anything that has ever been played, and the rapidity with which the music moves through sections and styles means that the players have to be subservient to the music, and work up to it, instead of the other way around.

“The sound is the hard part to get, a group sound,” Mr. Marsalis said. “There are things that are difficult to execute in terms of music, but the concept, to get it to sound right, is the hardest part.”

Mr. Marsalis acknowledges a debt to his band members. Phrases and aphorisms that had been tossed around on the long bus rides during concert tours have been incorporated into the new composition. “All of the guys in the band come from the church, and they’ve really influenced me,” he said. “They’ll be singing the church songs on the bus. It’s around them all the time, so there’s a deep connection to spiritual tradition. I didn’t have it in terms of going to a particular church, but I had deep faith in belief. Spiritual matters are fundamental. Look, the fundamental cadence of the blues is the ‘amen’ cadence.”

By Peter Watrous

Source: New York Times