Wynton Marsalis’s ‘Spaces,’ a Kinetic Series of Zoological Portraits

The kazoos cropped up in the 10th and final movement of “Spaces,” an episodic suite by Wynton Marsalis that had its world premiere at the Rose Theater on Friday. The Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra was swinging light and fast as it happened, bzz-bzz-bzz-bzz-bzz, in a busy rush. It was a cute and clever flourish, in a piece titled “Bees Bees Bees.” And it was also an act of evocation that reflected the larger theme of the suite.

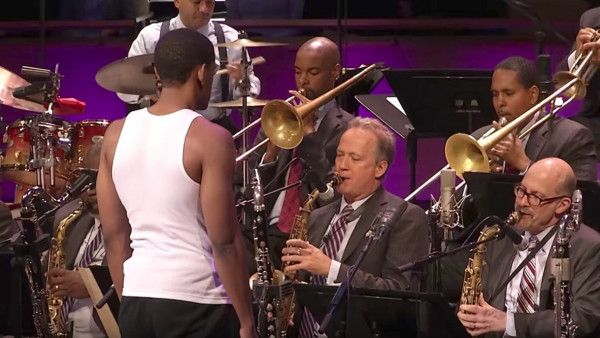

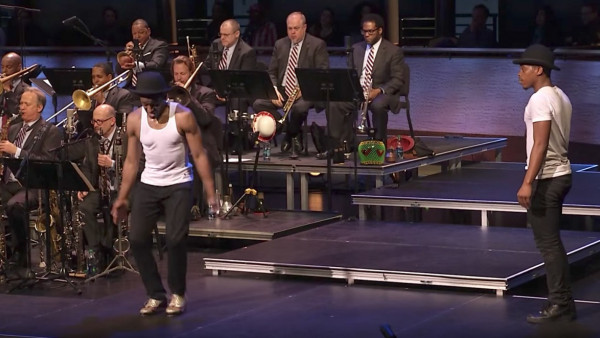

Mr. Marsalis, who as artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center has always drawn parallels between jazz and other forms of human expression, designed “Spaces” as a kinetic work: Its star soloists were dancers, Lil Buck and Jared Grimes. The music often felt subordinate to their physical exertions, though in the suite’s best moments the two sides were inextricable, each feeding the other.

“Spaces” was also conceived as a series of zoological portraits, and it was in this respect that the composition found its footing. Those buzzing kazoos were just one example of Mr. Marsalis’s knack for a sort of musical onomatopoeia. (His precisely frenetic trumpet solo in the same piece extended the metaphor while recalling a youthful triumph, his tour-de-force classical recording of Rimsky-Korsakov’s “The Flight of the Bumblebee.”)

In similar fashion, the movement “Ch-Ch-Ch-Chicken” had the band’s reed section clucking and pecking on clarinets, against a clackety beat. “Pachyderm Shout” opened in a lumbering rut, with bowed bass and bass clarinet, before the action shifted to the trombones, in a testifying chorus of elephantine harrumphs. “Monkey in a Tree” featured a chattering cacophony among the saxophones — an outcry characterized as “loose-tongue signifying” in Mr. Marsalis’s remarks, which struck a typical balance between hospitable wit and elaborative instruction.

The general tone of the writing was occasionally nostalgic — emulating a society dance band in “Mr. Penguin Please” and Duke Ellington more specifically in “Those Sanctified Swallows.” At moments like these it was easy to focus entirely on the dancing.

But Mr. Marsalis also showed orchestral ambitions, arranging more than a few passages for a piquant blend of flutes and muted horns, and favoring striking harmonic sequences, like a Thelonious Monkish stretch of “Leap Frogs.”

During the dynamically fluid “King Lion,” the band, conducted by Damien Sneed, sped up and slowed down in unpredictable, sometimes overlapping waves. It was supposed to conjure a mental image of the hunt, but it registered mainly as a distinctive show of power and precision from a band with its own metabolism, whether at rest or ready to pounce.

by Nate Chinen

Source: New York Times