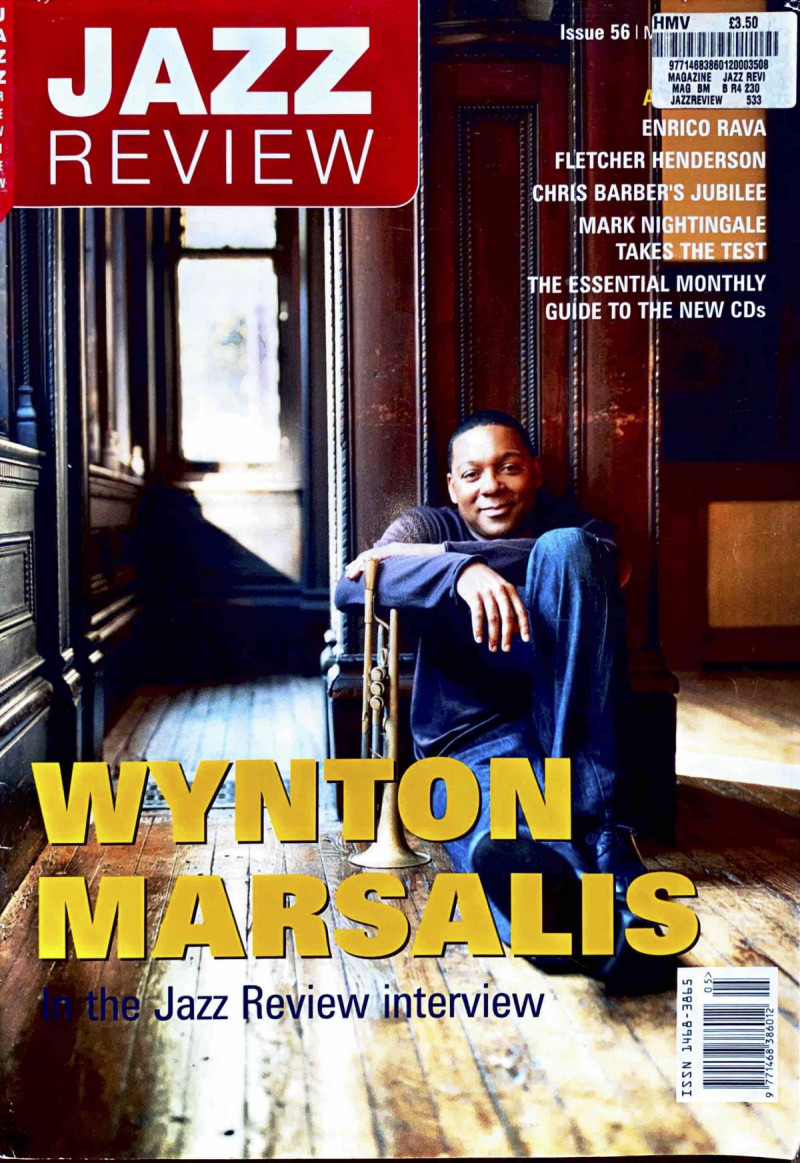

Wynton Marsalis: The Jazz Review Interview

Cover image: Jazz Review (May 2004)

He’s a busy man, but he’s immaculate – crispest suit I’ve seen in a while, hairline darkened and groomed to a pencilled exactness, the familiar playful smile always hovering around the lips. Jazz’s greatest ambassador, sipping tea in a London hotel, ostensibly promoting a new and debut record for Blue Note, but thinking always about the music – where it’s going next, and what he has to do to help it on its way.

Maybe we should look at a typical day-in-the-life of Wynton Marsalis.

“Every day is different. Let me go back over the past four or five days … today’s Thursday. Monday I had my class at Juilliard, two improvisation classes, the first starts at 9.30 till 11.30, then one from twelve till two. Nine kids in each class. Then at three o’clock I have various meetings, the building committee where we discuss our building, then I have to report to my various departments at Lincoln Center, a release for a brochure I have to do, uh, we’re talking about who’ll be lecturers for jazz, where are we at. whose artists we need, what other ideas there are. Oh – no, wait. before I came into Juilliard, I taught a masterclass at Moravia college, that was after a concert we did the previous night. Then in the evening I did a television show with Bob Kostas, a show called On The Record – was a good interview, too, he touches on subjects that make sure it isn’t a puff. Then after that I bad to take my two big sons, my 13-year-old and my 15-year-old, out, and then I bad a meeting with Bob Sagan, we talked about a record we want to do next year. Then next day I bad my Juilliard classes. Then I bad to read poetry at an event – lot of actors there, Kevin Kline, Vanessa Redgrave. Yeah, I was doing a reading, I like to read poetry – I did James Wilton Johnson, “The Creation” and ‘John Henry’. I love to read poetry. I was always reading it to my kids when they were growing up. And I’d perform and sing and dance round and act crazy, I enjoyed that! And yesterday, I got on the plane to come here.”

Today, be has a fat copy of Webster’s Dictionary on the table, along with a rather scruffy-looking notebook, which turns out to be filled with page after page of notes – on every aspect of his work.

“This is my notebook, this could tell you a lot about me. I have my objectives for everything in here. It’s sloppy, but I know what it is. Like, the first concert, when we open our hall in Lincoln Center, this is my objectives for it. This is the structure, the aspects of the programme which we’re going to highlight.”

On the page, in his affectedly neat but spidery hand, is line after line of bullet points and song titles and such. Wynton flips over a page.

“Then I study other people’s concerts – this is Benny Goodman’s concert he did, and I write down what all his pieces were, what they did … then here is Miles Davis’s Carnegie Hall concert. I have Duke Ellington at Carnegie Hall, the ’43 concert, this is the list of a Count Basie concert, all the songs … and this is from a meeting with Ornette Coleman.”

Ornette?

“I was round Ornette’s house every night playing with him, just the other week. I went to his house ‘round ten-thirty, eleven, and we were playing till about three in the morning. Ornette was real close with my father, because he lived in New Orleans for a while and he knew a lot of the New Orleans musicians. It’s almost a familiar thing, when I see Ornette, so it’s almost like I’m home when I’m with him, it’s like being back in my house! Soulful. Brilliant man.”

Wynton turns the page again.

“I do this satellite radio show, this is the notes I take for that. One of the things I do there is a music appreciation of contrasting styles – like, if I’m doing Don Ellis and Don Cherty, the Don Ellis record would be New Ideas, and the Don Cherry record would be “Cherryco”. They’d be the two songs I’d talk about. And then Harry James and Bunny Berigan … this is, uh, our programme, we had a five-year plan for the new building, this is how many concerts. These are leadership questions, what I want from the various people I’ve been with …

And there are pages of aphoristic sketches for ‘poems’, for his alphabet project, where jazz greats will be captured in words, portraits and music. With so much on the table – on the page, in meeting-rooms, in classes – it’s a wonder that he has any time to play.

“Well, if you were with me, you’d be like, damn, you’re playing all the time. How often do I see you? S***, I never see you, so obviously you don’t see me playing! If you was with me, you would!”

Bruce Lundvall, Blue Note’s now venerable boss, can claim a rather unique distinction in the jazz record business: he’s the only man who’s ever signed Wynton Marsalis. He signed him at Columbia – “Although he was gone after I did it” – and now he’s signed him again, at Blue Note. Business gossip had it that Wynton talked to everybody as his Columbia contract came to a close, but nobody could afford him. In the end, it was the last great jazz-lover at the high end of the record business, Lundvall, who did the deal. In a way, a daring signing, at a time when investment in instrumentalists at major labels is at a very low point.

“They’re fighting for their survival. They’re losing a lot of money every year.”

Well, it’s not quite that bad yet. They’re Just not making as much.

“Well, I haven’t seen their books. All I know is they’re not happy. They’re a business interest, and I don’t expect so much from business interests. They’re trying to make money, man. The money that’s made in our country with music is off of sexuality and charisma. Jazz will be around, because it’s difficult. Why is Bach around? Because it’s hard. Beethoven, he will be around – he ain’t going nowhere. And when the public really embraces him, and they have great Beethoven festivals, he’s going to be there. And when they don’t – he’s going to be there tool That’s what art is – it will be there.”

This is vintage Wynton. He loves the straight-from-the-shoulder metaphor, the suggestion that everything is pikestaff-plain if you’re prepared to settle back and clear the fog and reduce to essentials. It’s as if he’s aware of economic and political imperatives, but he thinks that – as a bottom line – to-thine-own-self-be-true can conquer all.

“The question for jazz musicians is, how can we make our art great enough to be there? How can we make it sophisticated enough, and hard enough, for musicians later than us to say, damn, how did they play that? Charlie Parker’s gon’ be _here, because he made his music so difficult that every alto saxophonist afterwards who touches the instrument says, damn, what was Charlie Parker thinking about? We don’t have to worry about this so much, apart from immediate survival – but so did Beethoven, so did Wagner. Louis Armstrong didn’t have to worty about it so much, be worked constantly. There are periods, where it goes up and down. But we’re going to be around. You want to stay around? Make your style be something nobody else can play. Make your music so sophisticated, so full of depth and profound emotion, that _it will be there.“

A tall order, perhaps, for musicians just trying to make their modest way forward. But it’s a useful corrective to some of the stuff which gets talked and written about Marsalis. It’s never easy to divine the presence of an ‘innovator’ in jazz – surely there have only ever been a handful of such musicians anyway, and it would be inappropriate to confer that stature on to Marsalis himself. For all the talk of his conservative, regressive tendencies, he still sounds like nobody much but himself. He may have appropriated accents from every part of the previously-spoken jazz language, but any experienced listener ought to be able to spot Wynton inside six bars or so – the defining virtue of every jazz musician.

“Well, I always bad my own style and my own sound, even when I wasn’t playing nothin’. In terms of my own music, and all the musical forms I’ve played, that’s not even … I’m 42, I don’t need to talk like I’m 19. I’m not in the position of, let’s see – we’ve seen, you know. Either you saw it or you didn’t. There’s nothing for me to prove that I’m one of the ones who played. That’s a conversation for 1985, not 2004.

“The question is not, are they there? It’s, can you hear them? Wouldn’t be the first time. Monk – it wasn’t until late in his life that people said, maybe be can play.”

Marsalis can play all right. In the often quiet and temperate surroundings of The Magic Hour, he goes through much of his armoury: blues playing, the mute, the idiosyncratic way he’ll squeeze a note at the start of a phrase (which may have something to do with the techniques offered by the Monette horn, since Guy Barker – who also favours that instrument – often does a similar thing). Without any other horns to stand beside him, he plays as freely and openly as he Ner has. What agenda did he decide to set for this opener for the label?

To sound good! I just wanted to play, man. Get my young guys that I’ve been playing with, all this time, that I hadn’t documented anything with, set up a format where they could play, and make a statement of continuity. At crucial points I always want to make that statement. That’s what I wanted to make when I made my first record, when I made J Mood, The Majesty Of The Blues_, Blood On The Fields and All Rise. There’s a continuity of this material. In the case of Blood On The Fields, there’s a continuity of all this material that comes from slavery, chants and songs and stomps and claps, that’s still here with us. In the case of All Rise, there’s a continuity of all the fiddle songs and all the things that Leonard Bernstein and George Gershwin, all these people, tried to bring to this music together. It’s a continuation of ideas. In terms of this record, there’s a continuation of older people passing things on to the younger people, of slow tempos, of the blues, of a walking bass, and a swing, and musicians improvising together on basic forms, and of playing like kids play -there’s a continuation of that. That’s my theme, that I like. To continue.

“We’re not surrendering, we’re still out here, playin’! We got young ones now. Ali Jackson, he’s 26, Henriquez is 23, Eric Lewis, 30, he’s playing. Contrapuntal lines, like nobody else. Ali, he’s from Detroit, and he’s playing in a New Orleans groove. Carlos, coming from the Latin tradition, bringing in all these other kinds of music. They’re playing with the old man now, and we swinging! We bring Dianne in, and she’s swinging. Bobby Mcferrin, he’s like a continuation from Pops, scat singing and clowning.

Pretty wild stuff on the final, title track, too.

“Not wild for me, man, I played like that in the 80’ – ‘Knozz-Moe-King’, Live At Blues Alley, I played like that on that. But with me, it don’t count! I noticed that, a document don’t mean much. In America, we’re looking at pictures of the Los Angeles riot – we’re looking at it, and there’s Latino people, black people, white people – but the words are saying “And the African-American community” – but you’re looking at it, and it’s like, wait a minute … so the documentation doesn’t mm much difference.

Like on Live At Blues Alley, all that wild trumpet I played when I was 25 – it’s like, it don’t count. It’s documented. If you wanna know, you go look for it, you don’t you look away.”

One doesn’t have to look far to find Marsalis. Quite apart from his enormous American profile, which has built him into jazz’s most famous face (and voice -which is still an unfiltered New Orleans accent, entirely unchanged by bis many years in Manhattan), some three dozen albums for Columbia/Sony have enshrined his music-making as comprehensively as any player of the contemporary period. How you feel about the ballets and the chamber works and the likes of the humungous All Rise may depend on your attitude to Marsalis as musical everyman. I prefer the bandleader and trumpet player, but something does tickle appreciatively about a giant music-label such as Sony being obliged to market a black musician’s ‘classical’ output alongside his hot jazz. It’s a complex discography, and the interesting thing is what will happen to it now that the trumpeter has departed the label.

“No, man, I don’t own any of that. That was the deal I signed, I don’t like it, but I live with it. It might disappear, but if it’s of sufficient quality, it’ll come back. If not, it shouldn’t. The musicians will bring it back. I want to bring Duke Ellington’s music more into the forefront, I want to do that, because I love his music and I think people will get a lot from listening to it. I write my own music and I play that most of the time, but his music is great and it should be heard, so as a musician, I’ll say, Duke Ellington, Duke Ellington. I’ll bring him back. Then other musicians will do the same. Composers who’ve yet to be born will say, wow, Duke Ellington. That’s what happens.

“I” had a good-ass time, man, I’m not complaining. One of my best friends is a doctor in New Orleans, he’s kind of crazy, and one of his favourite sayings is, man, you had a great run. Time to cut your losses, you had a great run!”

And Wynton is back with his love of a good catchphrase. Read cold, many of his speeches sound harsh or aggressive, but he’s actually laughing his way through a lot of what is on these pages. In my several meetings with him over the years, I’ve never found him in a dispirited or ugly mood. Only a man with considerable diplomatic skills could have got as far as he has in penetrating America’s cultural establishment, but Wynton is more like a neighbourhood politician: he loves to dispense homey wisdom, and as eloquent as he is, he likes to round off a point with a that’s-how-it-is sort of tagline, almost a cracker-barrel truism. In his Lincoln Center role, that may assist in getting past some of the red tape which cultural organisations love to freely dispense. With ten years in the job behind him, does he think that much has subsequently changed for jazz in America?

“No question. First, 1,200 musicians have got jobs, even if it’s just two nights a week. There’s been a lot more discussion of jazz. We’ve produced many premieres of music. We’ve commissioned two new musicians every year for the last ten years, so a lot of new music has been written. We’ve presented a lot of Duke Ellington’s music that wouldn’t have been heard. We’ve sent thousands of scores to high schools all over the country, and some of those musicians have become band directors themselves. We’ve partnered with the Library Of Congress and the Smithsonian to get a central jazz edition, scores that people can get. Lectures, jazz-film talks. And we gave a cause for hope for many musicians at the end of their lives. Benny Carter, who told me, man, keep this going. John Lewis, his last concert was with us. Gerry Mulligan, who called me and requested that we put on his posthumous concert. And he said to me, you pick the music out, and do it like a New Orleans funeral. Sweets Edison, sitting up there in rehearsals. Roland Hanna. Lionel Hampton. In terms of our education programmes, all over the country, it’s had a tremendous impact on younger musicians. In terms of the touring we’ve done, band directors bringing their kids to see us play, all the masterclasses our musicians have done. The swing dances we’ve played – we did one here, that was a swinging-ass dance, man! We played a television show with the New York Philharmonic and people all over the country saw that and went, wow, jazz! That’s just some of the things.”

Yet jazz barometers can also show a very different story. A tremendous retreat in major label support for instrumentalists, the declining club circuit, the perceived switch from ‘jazz’ as a living to a museum phenomenon …

“It is getting better, but in terms of the writing about it, that’s the tradition. If you don’t wanna see it, look away. That was the south’s theme song, ‘Dixie’ – ‘look away, look away … ‘Bad news creates bad news. Jazz bas always been written about that way. Record companies are dropping all kinds of people, man, not just jazz musicians. When I was first signed 20 years ago, nobody was signing jazz musicians. When I turned my record in, they went, Wynton, we’re not putting it out. We don’t like this, you should be playin’ pop music. But I didn’t want to do it. I stuck by playing. Out of my generation, I didn’t know anybody who liked jazz. None of my friends never said the name of a jazz musician. They didn’t even say they didn’t like it, they never said his name. So, is it better now than it was then? Yes, it’s better. Is that reflected in the way its written about? No, it’s not. Are there more young people playing jazz, having national careers on the scene? Yes.”

But how is Wynton Marsalis sounding now compared with 20 years ago? The brilliant young cat I heard at Ronnie’s in 1982 has matured into a major statesman, but how is he on the horn? The Magic Hour certainly gives him a clean canvas to work on. A calculating review in America’s Jazz Times, comparing the record with Dave Douglas’s (to these ears) largely overwrought Strange Liberation, complained that Marsalis has a predilection for cuteness which sabotages the impact of much of his playing. It’s true that playfulness can sometimes intrude on any sense of the grand design. But it would taken an awful good trumpeter to outdo some of what Marsalis sets down here.

“I’m better than I was then! You just play less notes, and you make ‘em mean more. Listen to ops – that session he did with Duke Ellington in ’62 ’63? All the trumpet he’s playin’ on that? Come on, man. You don’t have to give up.

Do you give up or do you keep going? I’m not ever going to give up, man, I made that determination when I was young. I tease my sons – when I’m dead, you’ll all come to see me on the cooling board, and my johnson is still going to be hard! And the doctor’ll say, cut that off!”

If he’s the most renowned figure in his field, he’s also among the most heavily criticised particularly in the jazz media. Marsalis may not have done himself many favours down the years – with some or his pronouncements, his sleevenotes, his use of Stanley Crouch as a kind of Boswell – but even so, some of the flak has been almost vindictively personal. As Wynton finishes his tea, I wonder if the criticism hurts.

“No. I’m too old to be hurt by it. It’s a cultural dynamic. Hurt? I don’t even think of it in that way. The amount or respect and love that you get, is so much, it balances that. You have to take both or those things, because iF you didn’t, you’d be insufferable. If you were with me, you wouldn’t believe how well some people treat me – so it’s good, in a way, to have that kind or antagonism. Even though a lot of it in my own mind is unjust, just in terms or the lies, not the criticism or my playing – just making up s***. I don’t respect that. Beat a man fair. But even with that made-up stuff, it just balances all the things that you get. Girls giving you their phone number, you being successful and stuff, people giving you breaks, taking care or you – it’s unnatural, man, that stuff which comes with publicity. And it doesn’t matter who you are, even if you’re grounded, you’re affected by it. I had the first newspaper article written about me when I was 14, it was called The New Gig, I can remember it – and I went from being just a person in the school to being someone who was celebrated. So you get things like people disliking you, but you get other stuff.

“At my age, it’s a sign or respect that I can be as criticised as I still am. Because when they do this” – and Wynton gently takes my arm – “they uncle you. I always felt bad for Miles, the type of critique he got, with his level of intelligence, he knew they was uncling him. You don’t want to be uncled, man – good ol’ Uncle Wynton. You wanna stay out here and have that scalpel put to you as much as you can. It means you’re still swinging. When they ain’t scalpelling you no more, it means. oh. okay. He contributed.”

by Richard Cook

Source: Jazz Review