Wynton Marsalis strikes a mellow note

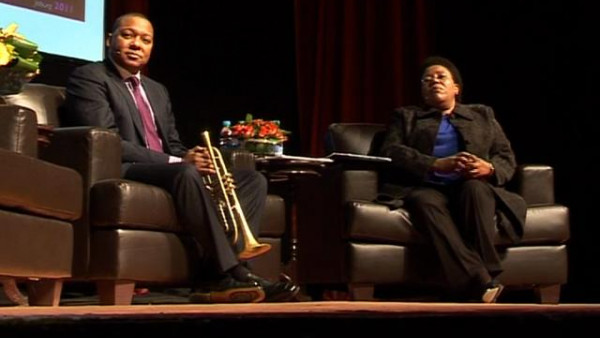

Trumpeter Wynton Marsalis (in South Africa for the Standard Bank Joy of Jazz festival), now approaching 50, is definitely mellowing.

As a guest of the Market Theatre’s 6/12 Conversation series on Tuesday, he was a model of self-effacing modesty: a man who’s still learning (“Art Blakey told me I sounded ‘sad’—and he was right”), who’s made more than his share of mistakes, who owes what he is to generations of trumpet-players as well as to his family and community. It was impossible not to warm to his humanity and humour.

And even if it had been, his closing rendition of Buddy Bolden’s Blues, played with maximum restraint but moving warmth, would have sealed the deal.

Yet it wasn’t always so. Back in the 1980s, when Marsalis was dubbed a “young lion”, he was outspoken, not only about the often racially loaded ways jazz players and playing were downgraded, but also about the skill of other players. The late Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians trumpeter Lester Bowie, he declared, simply “couldn’t play”.

Marsalis is a profoundly political musician. Building on the work of Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray, and working with the writer who has been described as “his Boswell”, Stanley Crouch, Marsalis developed a rigorously reasoned argument regarding definitions of African-American culture and jazz and successfully inserted those definitions into American mainstream debates and into the repertoire and policies of Jazz at Lincoln Centre (JALC), of which, after a great deal of paying his dues, he became musical director.

Killing the categories

What came to be called the “neoclassical” or “neoconservative” jazz movement was always a project with two faces. It was a necessary response to the rise of commercialised fusion music, but it was also very slick marketing for its own definition of jazz. It was a wholly righteous response to all kinds of genre snobberies and racist exclusions. As Marsalis said on Tuesday, “there is actually no ‘more’ of music in Beethoven than in a drunk singing in a bar—although it may be rather more interesting to listen to one than the other over the longer term”.

But it also built its own walls. In particular, as association trombonist Professor George Lewis notes: “By the mid-1980s, when new black experimentalists presented an event deemed as falling outside the — framework of jazz, neither the jazz writers nor the new music writers would cover it.” The work of exciting players such as Muhal Richard Abrams, Don Byron and others almost dropped off the radar.

Rightly, Marsalis demanded that musicians be asked to discuss their own methods and ideas, rather than being subjected to the analyses of self-appointed critics. But, when it came to the black experimentalists, he talked like the crassest critic, saying: “I don’t know anybody who enjoys that stuff.” And although Marsalis expresses a distaste many share for the sexist objectification of women in rap, Billie Holiday is the only woman to make it into the neoconservative jazz canon.

Jazz professor Eric Porter has noted how “Marsalis’s vision is also consistent with a discourse — that the problems of American society are to be solved by the reassertion of patriarchy”.

He’s also a damn fine—often breathtaking—player and makes a genuinely intriguing festival guest. The Market Theatre’s In Conversation, for the first time ever at Joy of Jazz, began to lift the curtain on the ideas underlying the music.

The past decade, in which Marsalis has been an acknowledged authority but far less of a media phenomenon, seems to have given him the freedom to mellow and explore music outside the canon he helped to fortify, using judicious pinches of youth and street music in From the Plantation to the Penitentiary, and collaborating with Ghanaian master drummer Yakub Addy on Congo Square.

We heard the neoconservative voice only once on Tuesday. John Kani lamented the conservatism of South Africa’s older jazz fans who, “when you play them something new, say: ‘That isn’t jazz!’”. Quietly, Marsalis added: “And a lot of it isn’t.”

Drawing the crowds

If you don’t already have tickets by the time you read this, you may not hear Marsalis play. All of his concerts have been sold out for a few months, although Computicket may get a handful of ticket returns. As Saturday’s Dinaledi Stage tickets also cover Tutu Puoane, Sibongile Khumalo and McCoy Tyner, it’s not clear how you’ll get to hear them either (unless there’s the customary level of sound leakage into the surrounding space, in which case everybody will hear too much of everything). Marsalis goes on at 11pm and the tent may seem emptier before then. The admit-or-evict dilemmas this will pose will demand skilful crowd control.

That leaves thin pickings around Mary Fitzgerald Square in terms of—“jazz” is such a contentious term—music based on swing and/or employing imaginative improvisation. There’s much flaccid fusion, some original creative sounds from the rest of the African continent, and Tania Maria, who swings, improvises and scorches.

Your best jazz bet may be the separately ticketed Bassline, with visitors the Tingvall Trio (on Friday) and DeeDee Bridgewater (both nights) plus a stellar South African line-up including Tyner’s reedman namesake, McCoy Mrubata, who sounds tougher and more interesting every time he steps out.

Growing through contradictions

In the Market Theatre conversation, Marsalis ruefully recalled being warned by Dizzy Gillespie that his outspokenness might haunt him all his life.

He’s still outspoken and it can still haunt him. He criticised the consumerism of hip-hop: just “men dressing in gold”, to Guardian music writer John Lewis in 2007. In the same year, the pages of American GQ magazine featured a dapper Marsalis advertising Movado wrist-watches, and the trumpeter’s fondness for a sharp suit significantly predates (and probably outclasses) Kanye West’s.

The contradictions exist because Marsalis is a human being, because all music is made by people living within societies, negotiating ego, economic systems and ideologies.

Marsalis is worth hearing and engaging with precisely because he grasps that there are discourses in all music and that choices need to be made. Because similar debate exists here too, it’s a pity more of South Africa’s “jazz” festivals don’t acknowledge that.

by Gwen Ansell

Source: Mail & Guardian