Wynton Marsalis reflects on the way time flies, as Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra plays a program full of his work

The Coastal Jazz and Blues Society presents the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis at the Orpheum at 8 pm on October 10.

WHEN WYNTON MARSALIS and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra play an all-Marsalis program at the Orpheum on October 10, it will mark a significant departure from their usual practice: honouring the giants of the jazz past by reconstructing their music for the jazz present.

Previous JLCO concerts and recordings have honoured such foundational figures as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, bebop and post-bop innovators Charlie Parker and Charles Mingus, and even relative radicals like fusion pioneer Chick Corea and free-jazz mastermind Ornette Coleman. But as the ensemble’s artistic director since 1991, Marsalis has always been shy of presenting his own work with the band in such a comprehensive fashion.

With Marsalis due to turn 62 this fall, should we see this change of focus as some kind of career overview or retrospective?

Not on your life.

“I’m not a nostalgic person,” Marsalis says, with typical directness. “I’m not like ‘It was great in those days.’ That was never my thing. ‘The older cats could really play and the young ones can’t play.’ That’s not my perspective.

“I don’t really think about life in that way,” he continues. Sure, some of the pieces on the program might be, in their original form, like a Polaroid of where Marsalis was at when he wrote them, but the trumpeter and composer says that while they’ve changed, he’s changed, and life moves ever onward, everything is part of some greater continuum.

“I don’t really see that the time is passing and that 40 years went by. Life is brief.”

“You know, if somebody sees a picture of you in an Afro—an Afro from 1977, you know what I mean?—and they ask ‘Man, what was it like in the ‘70s?’ Well, it was like nothing except like how it is now,” he explains. “I was alive, and Afros were the style that we wore. And then when we stopped wearing Afros, gradually, we wore something else. But it wasn’t like all of a sudden people stopped wearing Afros and the quality of life changed to be like a movie about the 1980s.

“I don’t think anybody looks at their life in terms of what they did in a decade. I think they look at in terms of their life: when their kid was born; when they had an operation; when their parents died; when they got married and they got divorced; when they lost a job; when they got a job… You know what I mean? When they realized something. So for me it’s like that. I don’t really see that the time is passing and that 40 years went by. Life is brief. I know many musicians that have passed away, and in they end, they would say ‘Life is short. Is that it?’ It’s almost like university. Like, shit, it goes by fast.”

After briefly commiserating over the fact that we’re both in our 60s—“I was 19 for about 20 years,” Marsalis says, laughing—we return to the question of why the JLCO is concentrating on its leader’s work on its current tour.

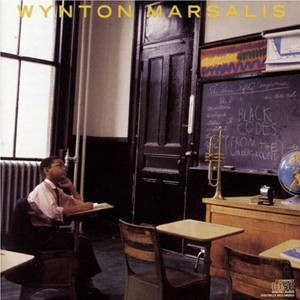

“It wasn’t at my suggestion,” Marsalis allows. But once the idea came up the other musicians in the JLCO embraced it, and even took on some programming responsibilities. “I went through maybe 400, 500 songs that I had and just picked things with different forms….And when I’d picked all the songs, Carlos Henriquez, our bassist, called me and said ‘Hey, you don’t have enough songs from Black Codes on here,” he notes, alluding to his 1985 artistic breakthrough, Black Codes (From the Underground). “‘You need to do “Phryzzinian Man” or you need to do these other numbers. You can’t do this without those songs.’ So there’s just a process that we use when we’ve been programming a season.”

Marsalis often speaks of jazz as the ultimate artistic expression of American democracy, and a prime manifestation of that can be found that eight of the JLCO’s 15 musicians have been involved in arranging his tunes for its current tour. Historically, arrangers have played almost as large a part in the evolution of big-band jazz as composers, and given that Marsalis defines the JLCO’s mission as “giving an orchestral voice to small-band music” that’s also the case here. But most of the classic big bands relied on one or two in-house arrangers for their scores. Having eight is either a luxury or a possible source of fragmentation, and Marsalis is obviously proud of the fact that with the JLCO, it’s the former.

“A lot of arrangers have come out of the band,” he says, “and we’ve played each others’ arrangements now for years. I think that makes the band unique in the history of our music; there’s never been a band with that many arrangers. And when we did the shows with Chick [Corea] and Wayne [Shorter], every time a new arrangement would come in, they’d be like ‘Who did that? Who did that one?’ ’Cause when I’d tell them we had eight or nine arrangers, they’d say ‘Of course!’”

Beyond that, the JLCO is essentially the Berlin Philharmonic of jazz: every chair is occupied by someone who’s at the very peak of their profession, yet aware that their collective success depends upon the quality of their listening as well as the intensity of their virtuosity.

“That’s how every collaboration is,” Marsalis concurs. “It’s like a large family: you can’t eat all the food just because you’re hungry. In society you have to eat a portion that is commensurate to what’s available and what’s allowable to eat. In democracy, there has to be a lot of self-assessment and self-policing—and in our music, because we have all these kinds of open forms and the freedoms we do have, we always have to be cognizant and aware of each other.”

So it’s a case of “from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs”?

“Most definitely,” the bandleader says. “That’s what we’re negotiating all night!”

by Alexander Varty

Source: STIR Arts & Culture