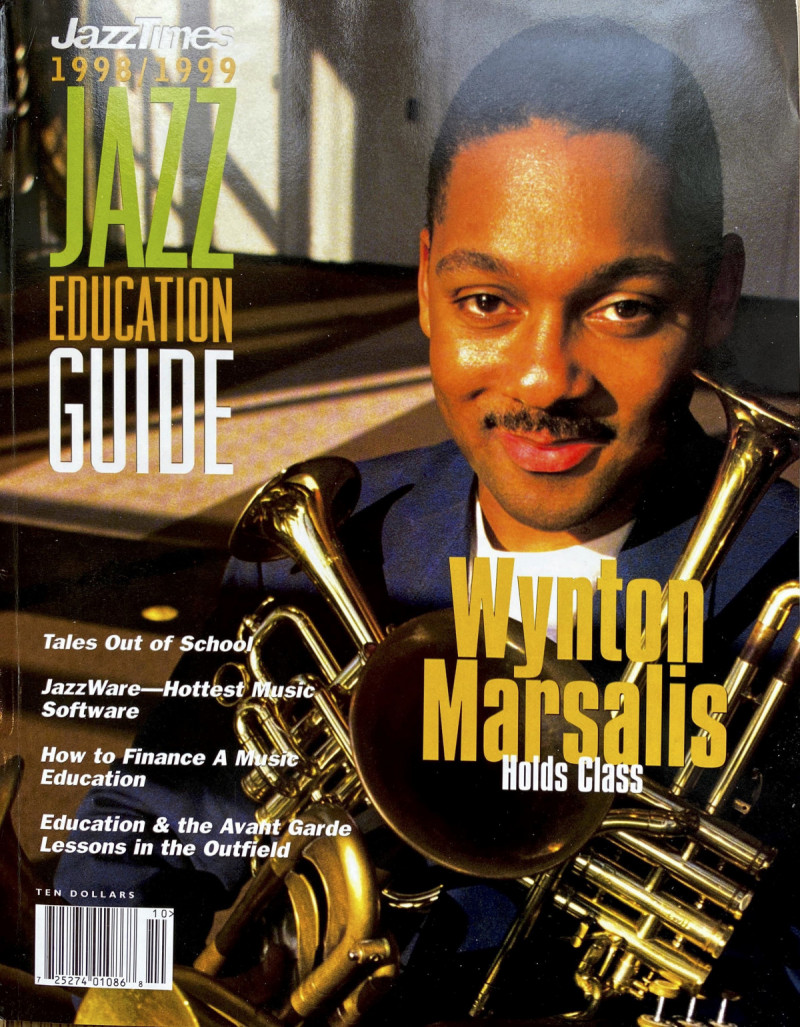

Wynton Marsalis On What’s Right And Wrong With Jazz Education

Cover: JazzTimes Education 1989/1999

From his formidable pulpit of Jazz At Lincoln Center, Wynton Marsalis is deep in the shed of jazz education, reaching out to children of all ages, developing curriculum material for teachers, concerned not only with pedagogy but also with audience education. Our conversation on the current state of jazz education focused not only on the classroom and the development of jazz musicians, but also on their obligation to the audience-and the need to expand that audience.

What’s the current state of jazz education?

I think it’s very good in terms of the number of people who are participating; of course, we’d always like to see more education for people who are not going to be musicians. But I think that there are a lot of bands, a lot of teachers, and a lot of students. In terms of sheer numbers, it’s good.

How about in terms of quality?

That’s what we have a problem with. But the one thing that makes me hopeful is that even though we have a lot of problems, cunously enough, we don’t have a lot of resistance. It’s not like dealing with jazz wnters, where quality is bad and you have a lot of resistance. But you don’t have th I . I at resistance with music educators, and certainly not with the students; the students never actually resist the information. Basically, the tone is set by the teachers and the parents. We have to do a better job of getting really good information to our kids.

How do we improve that deliver Y system?

We have to identify the things that jazz really teaches the students. There’s a reason to study jazz, it’s not to get in a competition and win or lose … we have to identify the things that jazz teaches the student, and we have to stress those things.

What are the critical needs of jazz education?

The first thing is to teach the students how to play with individual expression. A lot of time the kids who play in jazz bands don’t get to solo. If you have 20 kids in a class and you have one hour with them twice a week, the more general your lesson plan the more successful you’re going to be teaching that number of people. It’s hard for you to really give personal attention to each student. The issue is to have as a part of your teaching philosophy the concept of individual expression. Instead of the kind of clinical sterility of a certain type of ensemble perfection, make the students realize that you don’t have to sacrifice that ensemble expression because you play with individual expression. That’s the thing that’s so great about Basie’s band or Duke’s band: they’d play these tricky passages and it would be precise, but you could still hear the individuals playing it.

What’s the root of that disparity?

It’s philosophical; it’s a lapse in philosophy. Most of the problems we have in education do not have anything to do with numbers. You could have only three students and you could teach them poorly.

Is there a shortage of quality jazz instructors?

It’s not so much that. If you talk about all the teachers in general, a lot of general music educators are not taught jazz at all, so consequently they don’t feel comfortable teaching jazz. If we’re talking about jazz educators, a lot of jazz educators do know about teaching jazz.

Is one of the needs an increase in the numbers of actual jazz practitioners in the classroom?

Not necessarily, just that people know how to teach.

What are the most important tools a student should complete a proper jazz education equipped with?

*The first thing is a knowledge of the vocabulary; that they have listened to some recordings and they know, they have a historical vision of jazz, that they’re not taught jazz in historical segments -that’s one of the great failings of education. that’s like format radio.

Teaching jazz chronologically is not the way?

No, I think that’s a mistake.

Instead of that kind of linear approach. what would you suggest?

I think they should be taught in accordance to what things help you to develop specific skills.

Regardless of dealing with historical factors?

Yeah, because that’s not important – it’s important in a history class, but it’s not important if you’re trying to learn how to play. Certain things in the foundation you have to know, because they only exist in that. Like, say, the style of Louis Armstrong; I’d like to see the students be able to play some of Louis Armstrong’s music and then some of Omette Coleman’s music, because it’s not that far apart. You take somebody who doesn’t actually know, and you play them two things, and they’ve never heard any of this music, if you could have the sound quality be exactly the same nobody would actually know. If you didn’t tell them which style came before which – there wouldn’t be this type of bias. It’s also important to stress the blues and the whole aspect of play, that you play our music-interaction between the different instruments, being able to play in balance, and developing a concept of virtuosity on your instrument, knowledge of harmony and all these things, but from a hearing standpoint, not from a paper or technical standpoint.

What are the inherent disparities in a chronological approach?

The chronological approach makes you feel like you’re dealing with something that’s like technological advancement; like it makes you think that “OK. we had the 747 [airplane) and then we had the 767 and then we had the … “ But music doesn’t work that way; no art works that way. Duke Ellington might have figured out something nobody else is going to figure out, so you won’t get any advances on what he did, that’s just what it is. It’s like Bach’s music, if you want to write fugues you still have to deal with Bach.

In your Jazz At Lincoln Center education endeavors are you working from a master plan or is it designed as the project develops?

We have a master plan but we develop as we go along because we’re learning too from the students and the educators, and we get good ideas from different people and we incorporate them. We’re always open to different suggestions.

The July 2 Live From Lincoln Center PBS broadcast with the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra had an intriguing intermission segment featuring yqurse/f and some of your band endeavoring to unravel the “mysteries” of improvisation for the nonmusician. There are more than enough qualified and developing jazz musicians; there is precious, little audience. Where do you see audience development entering this whole jazz education equation?

That’s a very good point, that’s the point I actually kind of touched on when we first started talking: jazz education for people who are not jazz musicians. If you take some people out to hear jazz who’ve never heard jazz … just a typical person who grew up and they like James Brown, or Marvin Gaye, or Luther Vandross, when they go to concerts they’re used to seeing a show. You’ve got some distractions, you’ve got the women, you’ve got the lights … When they go to sit down in a [jazz) club and somebody stands up and the first tune all five members of the band take a solo so that one tune is like 15 minutes. Then they do the next tune and they do the same thing, in the same order-people just don’t want to hear that. But the jazz musician, a lot of the time we cling to that same archaic form, which does not work. It’s not so much because of the length of it, it’s just because it’s boring and it’s not well played. So we have a mutual problem: One is that we don’t have general (jazz) education for the audience, which is a very hard thing to figure out how to address, mainly because the education time is all taken up in school.

Every subject is fighting for more time for the general student population. Secondly, we have a situation where the [jazz) musicians have lost so much contact with the people that, either they say “We don’t play jazz, we play funk” or something like that, or else we go into an increasingly elite kind of music that nobody wants to listen to and say ‘fuck the people’ and just survive off of that. We’ve entered into a situation that’s counter-productive for both [musician and audience). and then the musicians start to question jazz. How many times have I heard someone say “People don’t want to hear jazz.” It’s not that they don’t want to hear jazz. it’s that we’re not playing it good enough for them to want to hear it. If Charlie Parker was out here playing, they’d go hear him play. Don’t think that the fact that it’s jazz is why the people don’t want to hear it, it’s not jazz, it’s the way that it’s played!

How must musicians better communicate with the audience?

The first thing is to question what we’re doing. In respect to the form that we use when we play; in respect that we play out of balance so that when the audience sits down to hear us play, the drums are so loud you can’t hear the band. Question the length of people’s solos and the quality of the solo; the need for more ensemble and arranged music to compensate for the fact that the solos are not by and large the quality that should be going on all night…

A lot of musicians got intoxicated by Coltrane’s example of the Herculean solo.

That was a mistake, because that’s one man. What he could do, he could do; it don’t mean you could do it.

Is it time for some drastic editing on the length of the average jazz musician’s solos?

Length and quality. If you’re gonna play like Coltrane, play all night, but you have to recognize that you’re not playing like him. The thing with the jazz musician has been ‘if the audience doesn’t like the music then it’s Jazz. It’s like if I go out and play basketball and nobody wants to go see it then I say nobody likes basketball. They don’t want to see me play it. We have to realize as artists that we have to lift up our art. How many times have I heard musicians say, “I go out to hear music and the shit is so sad it’s depressing”?

At the Essence Awards you admonished the audience about not listening to jazz“you’ve got to start listening to our music.” How would you propose getting that audience to listen to jazz, since they’re not going to do that purely out of some sense of obligation?

That’s a very difficult problem, speaking of Afro-Americans, because we have very little involvement in any art, it’s painful but it’s true. 1 really don’t know what to do about that problem.

How would you recommend that the Essence Awards audience, for example, better expose itself to jazz?

Start purchasing records. We have a whole history of classic jazz records. Maybe you don’t like what somebody is playing, but first just get basic – Duke Ellington’s music, Miles Davis’ music; there’s got to be something in jazz that you like.

Let’s say I’m a member of that audience who is a jazz novice, I hear your remarks and I see you backstage after the show, so I ask how to get started.

I’d give you a list of records, a couple of books to read. Tell you what younger or older musicians are out here playing, different gigs around town, who to go check out. I’ve had this conversation many times with people. 1 get so many letters in my office from people talking about how they started listening to jazz and they checked out Nicholas Payton’s gig, or Danilo Perez’s gig, or they like Latin music and they checked out Chico O’Farrill’s record, or they like avant garde and I told them to check out such and such.

Can you recommend five jazz records to a novice?

I would have to know you so I could get a feeling for what you like. Sometimes 1 ask them a question: “what kind of music do you like?”

Let’s say I really enjoy Luther Vandross and Patti LaBelle.

This music is in different categories. The first thing I’m going to give you is some music that’s sweet, that you can make love to: John Coltrane’s Ballads and John Coltrane with Johnny Hartman. Then I’m going to give you some music with longer solos, complex solos, but where you can hear some interaction between the musicians: It’s Monk’s Time, people like that record because they like the cover and they like the shuffle of those tunes. Charlie Rouse is on it and he’s stretching out.

I’m going to give you a recording that’s very sophisticated music, with complex orchestrations to give you an idea of the breadth of the music: Masterpieces By Ellington; it has “The Tatooed Bride,” “Sophisticated Lady”-and I want you to pay particular attention to ‘The Tatooed Bride,” and I want you to check out how [Duke] takes that one little theme and notice how he plays it in different ways. Now I’ve gotta give you a singer, something that has the real true feeling of the blues in it: any of the Billie Holiday records on Verve. Then I’d have to give you the perennial classic, Kind of Blue by Miles Davis. You’ve gotta have that just because that record shows you how to hear the personality of different people in their solos. Miles Davis is like the hipster; Cannonball Adderley was the school teacher, John Coltrane is like the preacher, and Bill Evans is very introspective. Then I’d have to give them one other record that’s just kind of some stuff with some people firing on it, that would be either Coltrane’s Transition or Charlie Parker.

OK. now how about the hip hop-obsessed son or daughter, who was mildly interested in what you had to say and wants to check out jazz?

I would suggest musicians who are recording today; whatever records have grooves on them. Danilo Perez’s record PanaMonk; check out Duke Ellington’s Far East Suite.

But Duke isn’t recording today. Do you really think he’d appeal to a teenager?

Tell him that Duke Ellington is 16 [laughs]. He won’t know. Just play the CD for him without him knowing; just tell him this is some 16-year-old kid they found in Maryland and this is what he put together [laughs!. I’ll just name the musicians that I would get him: Cyrus Chestnut, Joshua Redman, Marcus Roberts (Deep In The Shed), Nicholas Payton, Russell Malone. I’d let him listen to the music first and then I’d take him to hear them. He might not like it but he will at least know they’re out here playing. But I wouldn’t just give him the CDs; J would listen with him and pick out the shortest track and say “Man let’s check this track out”, four or five minutesanybody can listen to that.

But suppose the parent says “You know the last time l tried to take my kid to listen to some Jazz, the bass player took a ten minute solo.”

[Laughs] Well there’s nothing we can do about that, we’re still IO or 15 years away from solving that one … What you’re saying right now, I’ve had that conversation. But the one thing I tell them is that in no instance should they attack the music that their son or daughter listens to because when you do that that makes them want to listen to it more. That’s something I learned from my daddy; when we listened to all that bullshit he wouldn’t say nothing, he would say, “That’s great, man.”

What is the musicians’ obligation to educate the audience, and shouldn’t that also be a part of proper jazz training?

It’s important to understand that the audience is just like you. It’s good to go out to somebody else’s gig. Just like you can go to somebody else’s gig and notice things you don’t like about it, that’s how the public deals with it. A lot of my training as an artist came from people in the audience who would come backstage and tell me what was wrong with what we were doing. When I first came out here I just came out and played, it wasn’t that I didn’t want to say nothing, I just didn’t say shit: ‘This tune is this.” I wasn’t going out of my way one way or another.

Some musicians used Miles Davis and his Jack of onstage communication as an example, but he didn’t really have much of voice to communicate.

It wasn’t just him; Trane didn’t communicate that much, Ornette Coleman didn’t communicate that much. Most of the bands after awhile didn’t really say too much. There’s nothing wrong with not saying nothing; classical musicians never say anything. It’s not like you’re required to say anything, but you’ve got to realize that in some way you’ve got to make it so that the public can have access to what you’re playing; it don’t have to come through talking, but it’s got to come through-like the MJO had all these great arrangements, had great variety in their music, so the music would entice you. But when you have the same form on every song and the band is playing out of balance, and the solos are too long and not that good, and you’re not saying anything, it’s too many things to expect from the audience. Some kind of way in some arena you’ve gotta reach out to people, it’s up to you to determine how that’s going to happen.

Is there anything student musicians need in their training that helps them develop a better sense of audience communication?

I don’t think they have to be trained to do that; they just have to know that the audience is the key to their success. A lot of times the musicians think the key to their success is critics or the record companies. The key to your success as a musician is your ability to communicate to that audience, and that doesn’t necessarily mean talking. If the musicians would understand that the audience is your friend, that’s the only friend you have out here. When the audience accepts your sound and they get in your corner, and they say, “OK, I like what this man is playing,” they will stick by you. Critics can say, “That artist ain’t shit,” people will still come out if you provide them with what they want. Your responsibility is to give them 100%, and they know when you’re doing that.

by Willard Jenkins

Source: JazzTimes