Wynton Marsalis and JLCO colleagues swing their own tunes at Symphony Center

We’ve known for a long time that the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra stands as an ensemble of virtuosos.

But that term generally refers to the level at which musicians play their instruments. In the case of the JLCO members, though, it also signifies the way they wield their pens.

The program that brought the band to Orchestra Hall at Symphony Center on Wednesday evening cast a welcome spotlight on how these artists compose. For the repertoire did not feature the acknowledged masterpieces and forgotten treasures at which this organization long has excelled but, instead, works written by its versatile personnel.

That’s a far distance from the program the band played during its first appearance in Orchestra Hall, nearly a quarter-century ago in September 1992. On that night, what was then called the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra — making its Chicago debut on its first national tour — offered an all-Ellington program exploring various facets of the master’s wide-ranging art.

Since then, the band has established itself as the world’s pre-eminent large jazz ensemble, and music director Wynton Marsalis has encouraged his colleagues to add to its book. The value of that approach was apparent throughout an appearance that crowded Orchestra Hall, the large audience accommodated via the terrace seating behind the stage (though when the band plays the more typical Friday-night installments of Symphony Center’s jazz series, extra seats on stage usually are required).

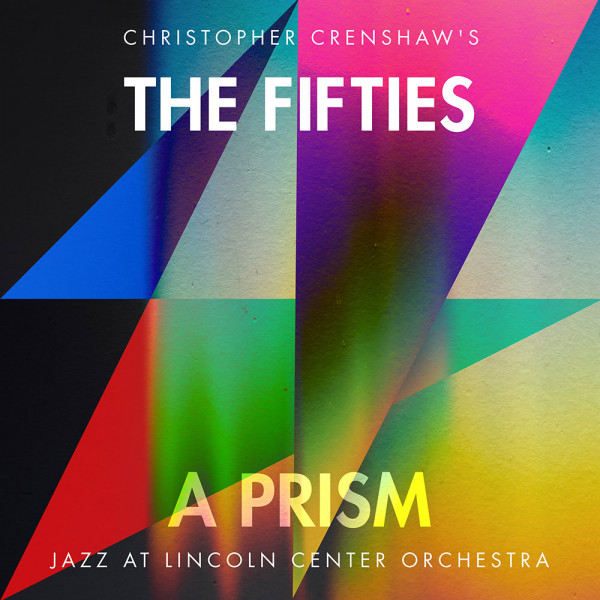

The evening’s tour de force came from the vivid imagination of trombonist-composer Chris Crenshaw, whose “Pursuit of the New Thing” was drawn from his aptly named suite, “The Fifties — A Prism.” Each movement of the work illuminates a particular sound of that fertile decade in American music, the “New Thing” finale addressing the innovations of alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman.

Yes, you could hear the longing blues sensibility that coursed through many of Coleman’s melodic lines and the nonchordal, profoundly linear way of structuring music that defined Coleman’s “harmolodic” methods (a self-styled idiom that was as widely reviled at the time as it is broadly revered today). But Crenshaw extended that philosophy across an orchestral palette, at the same time handing considerable musical responsibility to alto saxophonist Ted Nash and trumpeter Marsalis.

Without mimicking the work of Coleman and trumpeter Don Cherry (who revolutionized jazz in the late 1950s alongside bassist Charlie Haden, drummer Billy Higgins and others), Nash and Marsalis captured the freewheeling sense of melody-making and stop-start rhythmic elasticity of Coleman’s syntax. The orchestral interruptions and interlocutions added to the elements of surprise, which were ample. So much so that some in the audience applauded more than once for what they understandably believed to be the end of a composition/improvisation that was not yet finished.

For those who lament that jazz today lacks humor, Crenshaw’s “New Thing” argued deftly to the contrary. A spirit of subterfuge and comic timing drove a great deal of this piece, as did its poetic lyricism. Perhaps only two musicians who have worked together as long as Marsalis and Nash could have played this cat-and-mouse game so nimbly.

Nash, who recently won two Grammy Awards for music from his “Presidential Suite” (recorded by the Ted Nash Big Band), led the JLCO in the work’s “Jawaharlal Nehru” movement. The composer explained that he crafted its themes to reflect the tonal inflections and cadences of Nehru’s vocal delivery, and indeed its incantatory nature and narrow pitch range evoked human speech. But the movement’s shimmering ensemble colors and slow-but-sustained orchestral crescendo proved equally compelling, attesting to Nash’s translucent way of writing for large ensemble.

Among the evening’s other highlights: the slashing brass lines of a Marsalis “Offertory” from his “The Abyssinian Mass” (one of the best recordings of last year); the gorgeous reed-choir writing of bassist Carlos Henriquez’s “The Bronx Pyramid”; and a tender evocation of classic Dizzy Gillespie in Vincent Gardner’s “Ooh-Yadoodle-E-Blu For Me and You” (which closed with hypnotic orchestral vocal chant).

JLCO reedist Victor Goines, who’s also director of jazz studies at Northwestern University’s Bienen School of Music, gave the evening its most vivid passages of romance in “The ‘It’ Thing” from his “Untamed Elegance” suite. To hear Goines’ long, plush strands of melody on tenor saxophone set against a softly nocturnal orchestral backdrop was to realize, anew, the singularity of what these musicians can articulate in sound.

The Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra will collaborate with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in new arrangements of Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition” at 8 p.m. Friday at Symphony Center, 220 S. Michigan Ave.; phone 312-294-3000 or go to www.cso.org

by Howard Reich

Source: Chicago Tribune