Wynton Marsalis, Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra & Damian Woetzel – Spaces – New York

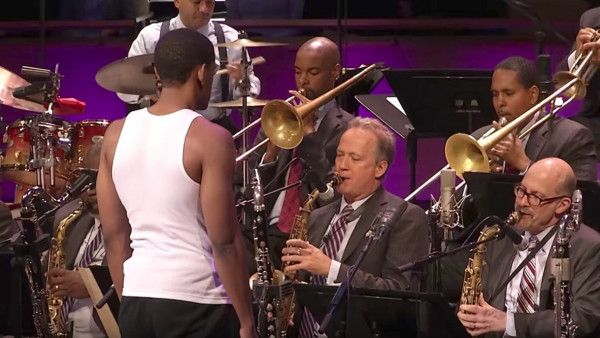

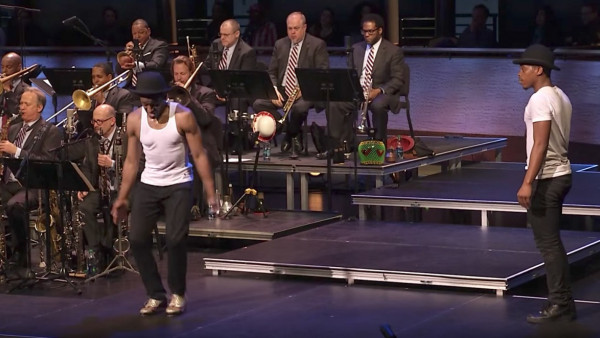

Lil Buck and Jared Grimes in Spaces. (© Lawrence Sumulong)

The Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra is a most impressive ensemble; as I listened to them play Wynton Marsalis’s Spaces at the Rose Theater last Friday, the Vienna Philharmonic came to mind. Their playing has confidence, virtuosity, luster, and a wondrous sense of play. Each player is a powerhouse in his own right, further magnified by the give-and-take of his fellow musicians. (And yes, I mean “his”; all the players, at least on this evening, were men. Even the Vienna Philharmonic has more ladies.)

Spaces, composed by the ensemble’s artistic director Wynton Marsalis in 2009, is a kind of jazz Carnival of the Animals, a suite that aims to capture the traits and quirks of this or that particular species. There’s the “Ch-ch-ch-Chicken,” and “Mr. Penguin Please,” “Pachyderm Shout,” and “Bees Bees Bees.” (Even the titles swing.) Marsalis, who plays his silvery trumpet in the back row, introduces each segment in prose both folksy and poetic, warm, erudite, and drily witty. He’s an able raconteur, virtuosic in his turn of phrase and generous in his use of the dramatic pause.

To this musical suite he has added, with the assistance of the show’s choreographer and director Damian Woetzel, the element of dance. The dance comments, illustrates and riffs on ideas and sounds in the music. Like Marsalis’s compositions, it’s neither banally literal, nor thoroughly abstract, but lies somewhere in the middle, deriving its inspiration and energy from currents in the music.

The original dancers, credited as co-choreographers, were Lil Buck and Jared Grimes, each a bravura performer in his own right. Buck is a master of jookin’–a gliding, rippling street-dance from Memphis – and Grimes a virtuoso tapper. Both dances, like flamenco and other vernacular forms, allow for a certain freedom. The structure is set, but within it there are many possible paths to take. Just as in jazz.

On this night, Buck was injured, but performed anyway, mainly with his upper body and arms – both expressive and articulate. Two more dancers were added: Dewitt Fleming Jr., also a tapper, and Virgil Gadson, a hip-hop specialist with a lengthy Broadway resumé. As in the original version, they danced, individually and together, in font of and around the band, sometimes covering broad swathes of stage, sometimes sticking to a small space, focusing in on the details of their refined footwork. As Buck told the dance writer Susan Reiter last year, he and Grimes share “the blessings of the feet.” It’s a sweet, and accurate turn of phrase; their ability to transmit rhythm, feeling and joy through their footwork is truly remarkable.

The result is an enjoyable, if not thoroughly electrifying evening of music and dance. Both the music and the dancing took a while to warm up. In part one, it wasn’t until the “Pachyderm Shout” that the band got into full swing. The musical compositions vary in style; they’re compact and convincingly attuned to the characteristics of each animal. Some, though, like “Ch-Ch-Ch-Chicken” feel more by the numbers. The corresponding dance, a spinning-pecking-strutting affair by Grimes and Buck, bordered on cute. “Monkey In a Tree,” with wild, dissonant chords, was more attention-grabbing. “Pachyderm Shout,” which began with a tuba-washboard-and bass combination, later developed into a screaming-wailing competition for trumpets and trombones (thrilling). And yet, it was was the least convincing as dance. “Leap Frogs” introduced a witty repartee between Buck and Grimes, both dancing on one leg (perhaps as a result of Buck’s injury). It ended with Grimes and Gadson leaping over each other into splits, a trick honed by the legendary Nicholas Brothers.

And yes, buried in these pieces there was a dose of history, with multiple references to past masters. “Mr. Penguin Please,” a suave big band number, was pure Ellington. And the accompanying dance threw in some Fred Astaire, some Charlie Chaplin, and a touch of Bob Fosse. Musically the highlight of the evening was “A Nightingale,” a sweet, lowdown piano blues. (Woetzel would seem to agree, since he had the dancers simply sit and listen.) Marsalis is a reverent student of his artform. But I was also struck by his sharp, unexpected juxtapositions of sound: the bass and cymbals in “Those Sanctified Swallows,” the sweetness of piano and flute in “A Nightingale.”

The dancing was excellent, if not always tremendously focused. Grimes, in particular, shone, with his jagged, playful rhythms, executed on every part of the foot, from instep to edge to pointe. Even injured, Buck exhibited his ability to lose himself in the music, his entire body vibrating to its sounds. Gadson was acrobatic and quick, a non-stop tourbillon of movement. Fleming, the least used, warbled and whispered with his feet. I would have liked to see more.

So much excellence on display, and yet, there was a certain flatness to the evening. Perhaps it was due to the episodic nature of the program, or perhaps it was the fault of Buck’s injury, but Spaces never reached the level of ecstatic play these musicians and dancers are capable of.

by Marina Harss

Source: DanceTabs