Wynton Marsalis Is Focus as Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra Opens Season

For the opening of the 2023-’24 season, Jazz at Lincoln Center did something it hasn’t done for a long time, if ever: It invited certain correspondents to attend the sound check at 4:30 p.m. at Rose Hall. It lasted about 40 minutes. At 7 p.m., the head of JALC’s education department, Seton Hawkins, hosted a pre-concert discussion with a longtime trombonist and arranger with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, Vincent Gardner, and then the actual concert kicked off at 8 p.m.

Something I heard at the soundcheck really intrigued me. As usual, the artistic director, Wynton Marsalis, used the opportunity to rehearse some key tunes as well as portions of others. Near the end, the Jalco played a segment from a larger piece that was unlike almost anything I’ve ever heard played by the orchestra, or almost any contemporary jazz orchestra, for that matter. It was a bouncy, two-beat slice of what could only be called big band dixieland, reminiscent of the old Bob Crosby band. What would the rest of this piece sound like, and how could they possibly transition in and out of it? Stay tuned.

For the first show of the new season, the Jalco chose to focus on the works of Mr. Marsalis. Generally, once every few years, he will choose to unveil a major piece of new music, usually a long-form extended composition. This time, though, the idea was to take shorter pieces from nearly a 40-year timespan and expand them into full-on orchestral arrangements for the 15-piece orchestra.

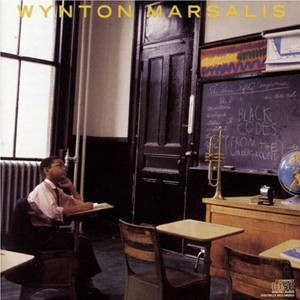

The concert was titled “Beyond Black Codes,” a reference to the 1985 “Black Codes (From the Underground),” perhaps the best-remembered of Mr. Marsalis’s early albums — and that was also the opening number, the only piece arranged by Mr. Marsalis himself. When adapting small-group works for larger ensembles, rather than getting heavier with the added instrumental presence, somehow they tend to get lighter and more user-friendly, as with the Jalco’s interpretation of John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme.”

“Black Codes” was originally one of Mr. Marsalis’s more progressive pieces, which seemed to exist in that transitional moment of the 1960s, somewhere between bebop and free jazz, a kind of compositionally driven, open-ended bop. Considering the musical content, as well as the titular reference to a rather brutal fact of African-American history, Mr. Marsalis didn’t want to soften its edges, but rather use the larger framework to bring out its inner meaning. “Black Codes” is still dark and menacing as well as swinging, and Abdias Armentos soloed on soprano saxophone, in honor of Mr. Marsalis’s older brother, Branford Marsalis, on the 1985 album.

Mr. Marsalis returned to the “Black Codes” album a few tunes later with “Phryzzinian Man,” another piece that evokes Andrew Hill, Wayne Shorter, and other mid-’60s composer-bandleaders exploring, in their own way, the space beyond bebop. As arranged by bassist Carlos Henriquez, this was the most modal tune of the evening, with an alto saxophone solo by Alexa Tartinino, subbing for Ted Nash, that had to be one of the most abstract improvisations I’ve ever heard on the stage at Rose Hall.

If the point of the evening was to illustrate the breadth and scope of Mr. Marsalis’s music over the course of what has already been a long career — he turns 62 in a few weeks — then it more than achieved that. While the “Black Codes” compositions are perhaps his furthest “out,” other works elucidated songs from all over the history of jazz. “Marthaniel,” written for pianist Marcus Roberts on the 1992 “Citi Movement (Griot New York),” has now become, in trumpeter Marcus Printup’s chart, a full-on orchestral concerto for blues piano, and one of the most soulful works the orchestra has ever played.

“Marciac Fun,” also arranged by Mr. Henriquez, from the 2000 “Marciac Suite,” shows the international range of this music. Inspired by a festival in France, the piece started with a Brazilian samba feel, and then, as it proceeded, gradually showed what a street parade in Rio has in common with a Mardi Gras street parade in New Orleans, complete with a section reminiscent of the Crescent City march “High Society.”

Several pieces also underscore Mr. Marsalis’s connection to the world of dance: “Awakening,” from the 1999 “Sweet Release & Ghost Story,” arranged by Ted Nash, is one of many he has written for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and other organizations.

“Speed,” from the 2007 “Here…Now,” also for Ailey, as arranged by Vincent Gardner, was inspired by an Olympic champion sprinter, Florence Griffith Joyner. It’s a highly baroque and staccato piece, in something of a concerto grosso format, in which, as Mr. Gardner described it in the pre-concert talk, seven members of the orchestra, reflecting Mr. Marsalis’s original septet, play in call and response with the larger ensemble.

In the second half, I did get to hear the whole of that mysterious two-beat number from the soundcheck: It turned out to be the ending of “Swingdown, Swingtown,” also from “Citi Movement.” As arranged by Sherman Irby, it reminded me of those occasions when the Jalco has played the music of Benny Carter, especially when he conducted the orchestra himself, and also the brilliant “Kansas City Suite” that he wrote for Count Basie.

Unlike the Ailey pieces, “Swingdown” was for social dancing rather than formal choreography, and it swung mightily in the 1940s big band dance music tradition. And then, all of a sudden, we were in a highly heterophonic, New Orleans-style dixieland moment: I was waiting for this, and yet I still couldn’t figure out how we got into it. As I scratched my head and looked around Rose, all I could see were 1,233 heads nodding to the beat, and 1,233 feet patting.

by Will Friedwald

Source: The New York Sun