Wynton Marsalis Goes Back To Church For ‘Abyssinian Mass’

Wynton Marsalis is sipping hot tea in a church conference room before the evening’s performance. His custom-made Monette Raja trumpet — with its built-in mouthpiece and black opal inlays — sits by his side. He’s riffing on one of his favorite subjects: the universality of rhythm.

“That rolling 6/8 rhythm is in African religious music, it’s in Anglican religious music,” he says, humming a complicated pattern and tapping his fingers on his notebook. “In a slower tempo it would be ‘Greensleeves.’” He scats the melody. “Now stay in that time, here’s the African 6/8 … now let’s go into the jazz shuffle.” More tapping. “It’s the same rhythm.”

“So all the musics are related,” he concludes.

Marsalis is going back to church. The 52-year-old Grammy- and Pulitzer-winning trumpeter, the artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, has created a sprawling work called Abyssinian: A Gospel Celebration. The piece, which amalgamates secular and sacred music, is currently on a 16-city tour.

“All the musics are related.” That’s a good way to get into the Abyssinian Mass — nearly two-and-a-half hours long, with intermission. This composition digs deeply into what Marsalis would call “the soil” of the black church: its shouts, its dirges, its spirituals, its hymns of praise. With this work, he celebrates the seminal influence the church has had on the music of black Americans, and the continuing pull it exerts on his own artistic and spiritual life.

Marsalis used the joyful stylings of the African-American gospel tradition to deliver a musical message of universal humanity. He says he tried to put it all in there: God and Allah, exultation and the blues, Saturday night and Sunday morning.

The Abyssinian Mass tries to cover a lot of different types of music and put them together and show how they come from one expression,” he says, “as the mass itself is about everyone has a place in the house of God.”

Back In Church

Marsalis was commissioned to write this piece for the 2008 bicentennial celebration of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem.

His composition follows the progression of a Roman Catholic service. When he was growing up in New Orleans, his mother, Delores, would take him to St. Francis Catholic Church, where he remembers the order of the mass from the Devotional through the Gloria Patri to the Benediction.

“I love the form of the Mass because when I was younger I was always wondering when would it be over?” he says. “I started to notice the form — ‘OK, when they get to this part, it’s almost over.’ “

Every section of Marsalis’ musical mass, like the Catholic Mass, is distinct from the other parts. His lithe, 15-piece band charges into the spaces in between, playing complex sectional counterpoint — horns against reeds — that would make Duke Ellington smile down from heaven.

The musicians say Marsalis’ creations are challenging. They always contain at least one passage that requires virtuosic playing.

“We’re so used to playing Wynton’s extended works we’re always looking for that in the music,” says Vincent Gardner, the trombone section leader. He has played with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra for 13 years. “So when we get a new piece, the first thing we do is flip through it and find the part that has all the notes. Because you know it’s in there somewhere. It’s just a matter of finding it and getting it under your fingers and then you can play it.”

‘The Breath Of God’

The Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra — regarded as one of the world’s best big bands — is surrounded onstage by the 70-voice Chorale Le Chateau. It takes its name from Damien LeChateau Sneed, the 34-year-old choir director and conductor of the mass. Sneed is a producer, arranger, conductor, teacher, keyboardist and sought-after gospel music director. He handpicked 70 of the top gospel and opera singers in the country — ranging in age from 21 to 70 — just for this tour. He says he plans to re-assemble this dream team for future projects.

“The choir brings the fire and the choir brings the truth to the Abyssinian Mass,” he says. “The choir brings the spirit, it’s like the haaaaaa, the breath of God.”

One evening concert in Charlotte, N.C., took place in an African-American mega-church, the Friendship Missionary Baptist Church. That made it special for many of the singers and players, whose first exposure to music was in a church pew. Sneed, for instance, grew up in the Baptist church in Augusta, Ga.

“I think every note, every phrase, every rest, every chord will have more meaning just because of the fact that we are allowed to express ourselves, not just in a performance hall, but in a place of worship,” Sneed says.

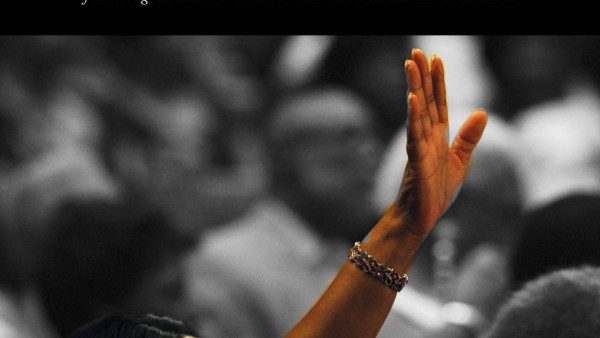

The choristers, in their burgundy robes, sing a cappella hymns in lush seven- and eight-part harmonies one minute; the next minute they’re swaying and hand-clapping to a swinging gospel number while the trombones growl in assent.

“The piece just has so many parts to it,” says mezzo soprano Patricia Eaton. “It was an extraordinary experience, it is an extraordinary experience. I’m excited and yet I am lifted to another place as a religious experience.”

The Abyssinian Mass sold out all 3,500 seats in the sanctuary of Friendship Missionary Baptist Church. The audience was also a congregation. They amen-ed and shouted encouragement and interrupted the performance with standing ovations.

After it was over, Dr. Clifford Jones, longtime senior minister at the church, searched for words big enough to express his reactions.

“Exhilarating, powerful, inspirational, affirming of both religion and culture,” he said, beaming.

An elderly African-American woman, who did not give her name, when asked what she thought of jazz and blues being played in her church, answered simply: “This is where it started, so it’s good to have it back home.”

Source: NPR.org