Wynton Marsalis debuts a stirring ‘Blues Symphony’

You can’t accuse Wynton Marsalis of lacking ambition. It’s right there in the title of his “Blues Symphony,” which the composer debuted in its entirety Wednesday night at Strathmore. And that says nothing of its scale. The piece is for 100 musicians (here, the Shenandoah Conservatory Symphony Orchestra), in six discrete movements charting the evolution of the blues throughout the Americas.

But the work perhaps tries to do too much. Its subject matter, coupled with its episodic structure — the movements marking off changes in time and geography, for example — makes it feel less like a symphony than an ethnomusicology essay, one that stuffs in too much information.

There are many wonderful moments, but their connections are often tenuous and confusing. The fifth movement shifts between evocations of the African American spiritual tradition and an exercise in shuffle rhythms. Both are highly enjoyable (if a bit obvious — the woodblock “cowboy” shuffle has been done to death), but the juxtaposition is murky: What’s the relationship being expressed? The second movement, the symphony’s weakest, compounds this problem by moving from an undulating “ocean” of strings to trombone solo to country two-beat. All of this is interpolated by a clarinet that too easily (and perhaps inevitably, in a classical-blues fusion) recalls Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.”

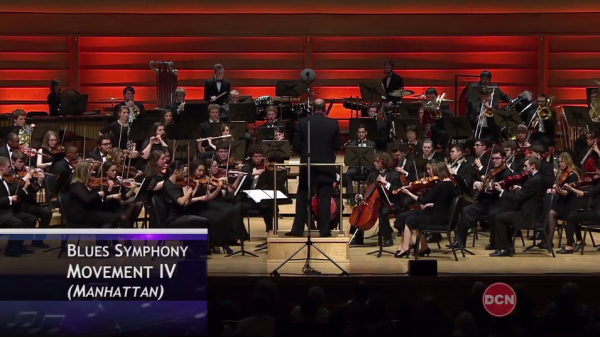

Still, there are exceptionally strong movements. The first makes the best use of the 12-bar blues form that is the backbone of the entire symphony, using it as a foundation on which to build patriotic American songs and marches, complete with stirring dissonance and inventive use of the piccolo. The fourth, a portrait of Manhattan, evokes the city’s drama and danger with staccato slants of strings and heavy, layered percussion (including the famous “spangalang” jazz cymbal pattern). And the finale includes an extended, full-orchestra ragtime workout. (A ragtime symphony — now that’s an endeavor someone should undertake.)

The musicians — all Shenandoah undergraduates — were terrific. Trombone soloist Nathan Davis did some of the evening’s best work. In the fifth movement’s high point, he and violist Erin Reilly traded improvised blues choruses. Clarinetist Jacob Moyer was also superlative, as was trumpeter Nathaniel Hussell, whose parts required him to pull hard at the harmonic edges.

It should be noted that before the “Blues Symphony” performance, Marsalis led his quintet through a full set. At nearly an hour, it was nonetheless an amuse-bouche for the main event — lively and accessible, highlighted by Marsalis on plunger-mute trumpet (a technique he has single-handedly kept alive in mainstream jazz).

If only the headline composition itself was as consistent as the elements surrounding it. “It’s been a long struggle to fuse jazz and the blues, our African American vernacular music, with classical music,” Marsalis told the audience. “And we continue to struggle.” So we do.

Source: Washington Post