Wayne Shorter Goes Solo With the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra

When the saxophonist Wayne Shorter has come through town over the past 15 years or so, he has generally been with his quartet, a group that plays soul-drilling, gonzo-Zen interventions on about 50 years’ worth of his music. There is much open space in these performances, much insight and mystery, a settling into a zone between direction and indirection. Apart from Mr. Shorter’s stature as a small-group composer in jazz — the best, pretty much — the alert and unscripted way the quartet operates has for many listeners represented a current ideal for how jazz works and what it can contain: immediacy, collectivity, discipline, freedom.

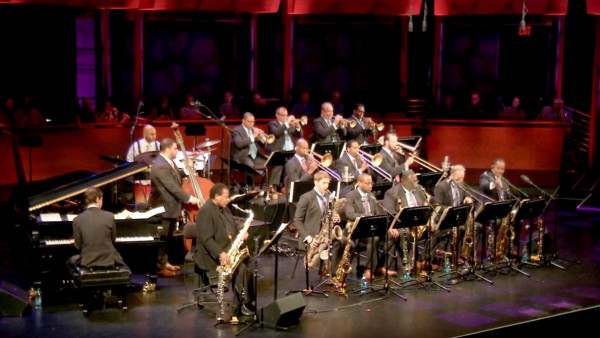

It’s not the only ideal, though. On Thursday at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater, Mr. Shorter, 81, did something different. He played a concert as a soloist with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra: new versions of Mr. Shorter’s compositions from his own records and others’, many of them not part of his usual repertory. The best known may have been “E.S.P.,” from Miles Davis’s 1965 album of the same name; the earliest was “Mama ‘G,’ ” first heard on the pianist Wynton Kelly’s 1959 record “Kelly Great.” All were newly arranged by various members of the 15-piece orchestra, directed by Wynton Marsalis.

And the concert, which was extraordinary, amounted to an inversion of how we’ve been hearing him with the quartet. (It was the first of a three-night stand, and part of a weekend-long Wayne Shorter festival at Jazz at Lincoln Center, with other groups playing his music in its other theaters.) Instead of Mr. Shorter acting as equal contributor to the sound-picture at nearly all times, here his improvising was restricted to a series of smaller window openings built into the large-ensemble arrangements.

He sat at stage left, looking good-humored, but did not speak to the audience. Mr. Marsalis, who’d interviewed Mr. Shorter before the concert for explanatory notes about the repertory, read out Mr. Shorter’s gnomic replies. About “E.S.P.”: “When you let go of things, other things come through.” About “Lost”: “It’s about not being afraid, even if you don’t know where you are.” And so forth.

In his improvisations, on tenor and soprano saxophone, Mr. Shorter didn’t play grand old man, delivering bravura statements with predictable arcs followed by obvious spaces for applause. Generally, either the end of his solos overlapped with the return of the ensemble arrangements or were directly picked up and responded to by another soloist in the ensemble. These arrangements were pointed and detailed, one quite different from the next; they gave you a lot to hear and demanded that you pay attention. They exposed the beauty of Mr. Shorter’s writing — the strange harmonic motion, the development of runic phrases — and suggested how much can be done with it. In any case, there was no easy grandeur enacted here, no possibility for corniness.

Within those window openings, he created startling, counterintuitive, exotic things. In Marcus Printup’s arrangement of “Armageddon,” Mr. Shorter played staccato phrasing through slow-swing rhythm section backing; luxuriated in fuzzy-textured notes and then stepped up into proud and assured ones; started blues lines and cut them in half, draining them toward silence in stepwise downward motions. In Mr. Marsalis’s arrangement of “Teru,” for five harmonized saxophones, Mr. Shorter played in defiance of momentum and the unbroken narrative. His improvising was free, gestural, with meaningful gaps around his phrases. And there was one major exception to the limited-window format: Mr. Shorter’s long, discursive solo in “Contemplation,” arranged by Sherman Irby.

The really breathtaking moments often weren’t in emotional surges — one of Mr. Shorter’s specialties — but in denouements. Like any musician, he’s got a few of his own clichés, but they weren’t much in evidence on Thursday. Mr. Shorter was taking ideas for a ride, working episodically with no fixed outcome, making quick and impulsive turns: discovering, basically.

by Ben Ratliff

Source: The New York Times