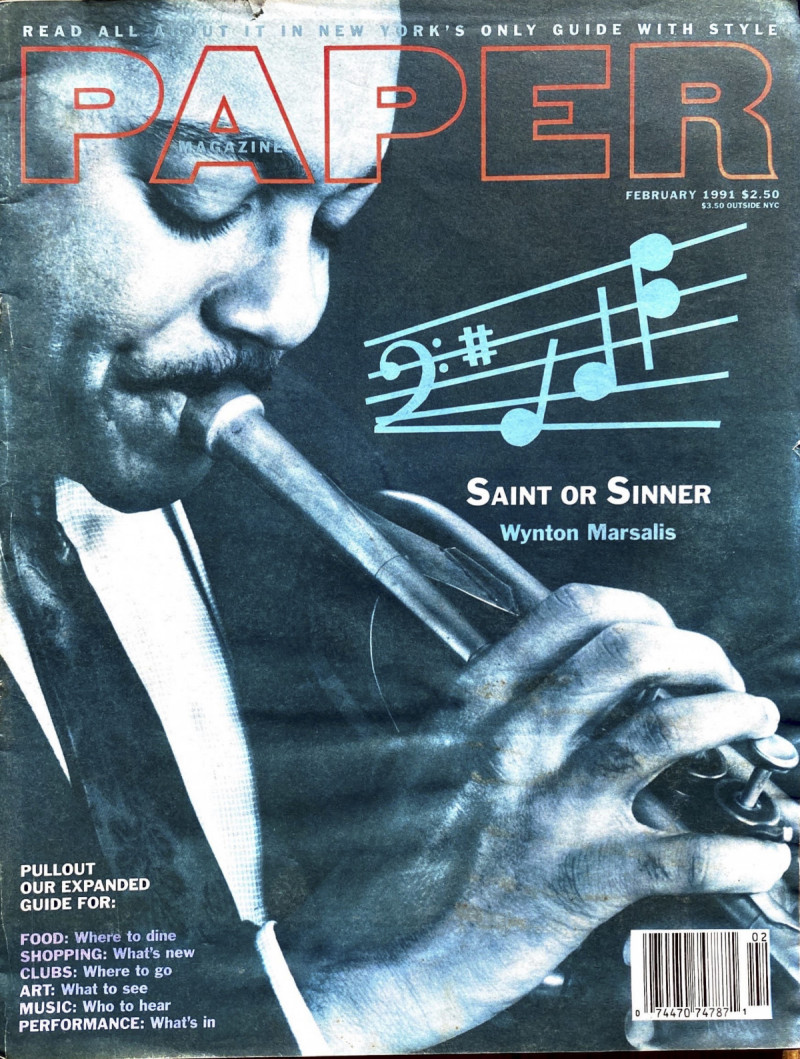

SAINT OR SINNER. When Wynton Marsalis comes marching in

PAPER Magazine (February 1991)

One. two. one. two, here we go,” says Wynton Marsalis as the videotape rolls and the band starts in on another take. On the monitor, a private eye is bringing a woman up to his apartment and Marsalis calls for some sexy sounds to accompany the scene from Shannon’s Deal, director John Sayles’ TV series that features an original score by Marsalis. One eye poised on the monitor, Marsalis leads them through a quick rehearsal. “That should be a g-natural,” he says. “O-eee-o-ay,” he hums to the horn section. Moving from the podium, he sits at the piano to demonstrate how he’d like it to sound and the band gathers round.

Moving about the RCA studio, he looks more like a basketball player (which he is) than the jazz world’s preeminent trumpeter. In a sweat suit and Nikes, his appearance is a far cry from the double-breasted dapper symbol of the new jazz age, Time magazine’s cover-story slick that’s become his trademark. But appearances can be deceiving; he’s as much in control in the studio as he is on the horn. There’s no messing around and the band is alert and obedient. Hand-picked and young, his ensemble knows the ways of Wynton and they are ready to follow their leader. Picking up a pencil in his left hand, he makes a musical notation, the huddle breaks up and the band moves back to their seats in the spacious confines of Studio 4A.

The band set, he waits for the tape to roll. And waits, and waits, one beat longer than he’d like to. “Will those who are bull-shitting please stop and show us the movie,” he says, directing his good-natured ribbing at the engineers behind the soundproof glass. And it’s “one, two, one two, here we go.”

Only a few bars into the song, he breaks it off shaking his head. “I need more of a vibe of consistency in terms of the phrasing of it,” he says in his liltingly soft New Orleans accent. “I didn’t like the way I came in. I was rushing it. This is the vibe. She comes in the room and the scene has overtones of sexuality. I want the music to come across as though it were a record in the background. Play the groove.”

This time they’ve got it. Marsalis points, gestures, mouths directions and nods encouragement. It’s played back and you can tell he likes it as a smile spreads across his face. He compliments the piano player and then it’s on to the next scene, the next tune, the next step in the life of this 29-year-old musician who’s emerged as not only the most important new jazz composer/trumpeter since Miles Davis, but also the most controversial. Almost singlehandedly, Marsalis has revived a type of jazz that had been largely comatose, if not declared dead as contemporary music. Rejecting experiments with fusion and the influence of rock, which shaped jazz’s direction since the ’70s, Marsalis has championed the jazz of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington over the bleatings of Kenny G. or the rock-influenced experiments of late Miles Davis. And he seems to be succeeding.

Wynton leads the pack, but right behind him a new generation of musicians, still in their 20’s, are riding his coattails – Roy Hargrove, Christopher Hollyday, the Harper Brothers, Marcus Roberts and others – playing jazz and, what’s even more surprising, selling records to a new generation.

Growing up in New Orleans, Wynton was part of a musical family that includes his father Ellis and brothers Branford, 30, Delfeayo, 25, and Jason, 13. But even in the acknowledged birthplace of jazz, America’s only original art form was virtually unavailable. One local club on the fringe of the French Quarter featured modern jazz with Ellis Marsalis as the house pianist. “When we were growing up,” says Wynton. “my daddy wasn’t working that much. Me and my brother (Branford) mainly played pop music. We didn’t play any jazz. We couldn’t play.

That’s number one. We didn’t know any traditional music so we couldn’t really call ourselves jazz musicians. Our daddy wasn’t pushing us into music. He didn’t say ‘Go do what I’m doing.’ Or ‘jazz is the only music.’ He was really trying to figure out what was happening, too. It was the ’70s; not that many people were playing jazz. The main thing we used to do was carry our daddy’s Fender Rhodes on gigs and we’d play on one tune a night.”

Obviously things have changed, as can be seen by the succession of recordings, most recently in Standard Time Vol 3: The Resolution of Romance (Columbia). Joining forces with his daddy Ellis, Wynton takes on a range of standards, from “I Cover the Waterfront” to “How are Things in Glocca Morra?” Is Wynton proud to be able to get his father the belated recognition he deserves? “You have to realize that when we were growing up we didn’t think like that at all. I didn’t know about national exposure or the media. I didn’t care about that. I didn’t look at music awards shows. We didn’t look at our daddy in terms of any external recognition. He was our daddy and he could play. And we couldn’t. We didn’t look at it as though, boy, they ought to be giving our daddy credit. He always had the respect of the musicians, people who knew him, so I never thought they were being disrespectful, but he couldn’t work playing modern jazz in New Orleans and now he’s more respected.”

In high school, the Marsalis brothers played for proms and dances, clubs and discos. And they studied classical music. Later Wynton would startle the music world by winning two Grammies, for best classical and best jazz album in the same year. “I was serious about playing the trumpet in classical music,” he says, “but I didn’t really pursue the music like I did jazz. I owned a lot more jazz records. I still don’t know a lot of the classical repertoire. I like the music. It was just what you did if you played trumpet. Some things are just what you do. If you’re in high school you go to a prom. You just go.”

One of his boyhood friends has also done quite well for himself. Harry Connick, Jr., a student of his father’s, was at the house often. “He always played me his tunes,” Marsalis recalls. “He was always a good musician and I could tell from the time he was a young boy that he had a good ear.”

At 18, Wynton Marsalis brought his horn to New York, studying briefly at Juilliard before joining the late Art Blakey’s band, an experience that changed his life. “That gave me a chance to see that in our generation you could get a chance to learn how to play by playing actual jazz,” he says. “I thought the only type of jazz you could play was this real sad fusion jazz because that’s all that was being played. But that’s not jazz, that’s pop music. I liked it but I didn’t think it was jazz. Jazz was something that had deep blues in it, swing, had a conception of virtuosity, had deeper levels of expression, had a spiritual connotation. Fusion was more pop music with the trappings of jazz. Like a hairpiece, it looks like hair, but it’s not. You know what I’m saying.”

Just what is – and what isn’t jazz is a matter of great contention these days. Marsalis’ purist approach has put him in opposition to the trend. “I’m all for Spyro Gyra and fusion and all of that. Kenny G. I believe they have a right to exist and play what they want to play but whether or not they’re in the tradition of John Coltrane, or an extension, elaboration, refinement on the music of Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk or Jelly Roll Morton… It’s inconceivable that people at one time even thought that. I don’t draw the line in terms of time, because the Modern Jazz Quartet has been playing jazz for a long time. I’m thinking purely in terms of music. I’m not thinking in any terms of time or cliches; I’m thinking in terms of harmony, melody, rhythm. call and response, riffs. breaks, polyphonic improvisation, the elements of jazz, the things that determine whether it’s jazz or not – that’s the battleground.

What I’m saying is that things can have elements of jazz and not be jazz. Jazz has a function, and that function is to illuminate, from a mythic standpoint, what American society has represented and should represent. And the whole question of fusion and whether it is jazz and that people argue about it is really ludicrous. It was funny to me ten years ago. Even when I was in high school it was very clear to me what John Coltrane and Miles Davis, when he was serious, and all those other great jazz players represented. Obviously the music we listened to didn’t represent that.”

Hold on there! When Miles Davis was serious? In saying that Marsalis was dissing one of the major jazz innovators and icons of out time. “Do you mean before Miles played electronically?” I asked. “Before he sold out,” he answers bluntly. “Before he started imitating rock musicians.”

Which brings us to another topic that makes Marsalis mad: Rock. I asked him about the oft-repeated comment (most recently by jazz critic Nat Hentoff writing in the Wall Street Journal) that he fired his brother Branford from the band after he decided to go on the road with Sting. “Let me ask you something,” he says.

“You work for NBC, then next year you’re working for CBS, making more money and on the road for a year. Is NBC going to have to fire you? Why is it that none of these writers ever thought about that? He went and played with somebody else. All the jazz writers have been saying that for years, once again trying vainly to stop something that they think is about me. They’re wasting their time.

Just report the facts. Why would I have to fire them, if they’re going to play with someone else? It became an issue because they were playing rock music. Me and my brother have been playing together our whole lives. Nat Hentoff wasn’t breaking his neck writing about him (Branford) in the early ’80s, when he was trying to play and get his stuff together. Everyone then was saying he couldn’t play.

‘He’s just in the band because he’s my brother.’ You know what I’m saying.

It’s a cold thing that goes down.”

What does Marsalis think of Hentoff’s description of him as a “saviour of old jazz?”

“Old jazz, new jazz, art doesn’t have an age on it. We have to go back to the Renaissance to find painters who had the kind of control Picasso had. Beethoven’s last quartet is written in the style of Haydn. Artists of that caliber are making these statements. Duke Ellington ‘till the end of his life constantly reworked elements of New Orleans music. I don’t see why there’s always a battle between the critics and the musicians in jazz. I’m not trying to fight them because the people are gonna come out to hear me play, the young musicians are going to come to my house, they’re going 10 study the music and they’re going to learn.”

Marsalis has also been accused of saying that white people can’t play jazz. Is there any validity to that statement, I ask? “I might have said something like that when I was 17,” he says somewhat embarrassed, but he believes there’s more to the attribution than meets the eye. “If you’re a black musician, you’re always perceived in terms of whether you would kiss the behind of the establishment or whether you won’t do it. And if you don’t do it, they attribute all kinds of asinine racist statements to you. And if you do it, they say you’re cool. That’s what happened to my brother and them (other former members of the group) in the press. When they started playing with Sting, they became great guys and famous musicians. When they were playing with me, they weren’t nothing.

You see, for me, the whole problem has always been that they can’t figure it out. He plays classical music, so maybe he’s with us, but he wears round glasses and suits so he’s not, but … It’s always some kind of strange attempt to put you in a political camp or to just discount individual actions. I’m not out to kiss any behind. I’m just out here to report as accurately as I can on what I think and see and feel and that’s it. So I don’t take a statement that’s dumb like that and elevate that.”

Apparently it has worked. But with recognition comes a responsibility, which he’s taken on both shoulders. In recent years, Marsalis has begun visiting schools and jazz workshops around the country to talk and teach. If he comes upon a musician he likes, he stays in touch, offering encouragement, exchanging tapes, and paving the way for their development. For his efforts, Marsalis is being rewarded, not only by the maturation and success of his protegees, but also by Lincoln Center, where for three years he has been the artistic director of Classical Jazz, the successful annual summer series. Beginning this month, Lincoln Center, the bastion of classical music, is adding a jazz department that plans to have an annual budget of $1 million by the mid-‘90s.

This brings to mind the fact that the great majority of people attending jazz clubs and concerts around the country are white. Why aren’t more young – or old -African Americans supporting their heritage?

“It’s that there’s no real exposure in the community. there’s no advertising of it on the radio and there’s no celebration of the great musicians,” he says. “When I say celebration, I mean true celebration, which is knowledge of their art, not knowledge of their name. If there was knowledge of this thing. it would be a lot different. And also the education system really has failed in our country in general. We have some really great features in our educational system but, from a cultural standpoint, we’ve failed. We have opened up such a big door for the music industry to exploit teen-age sensibilities and make so much money because there’s really no education.”

Does he enjoy any of the music he hears coming up from the streets? “‘It’s all these cliches being elevated. All these profanities. And it’s being made into something hip. That’s what kills me.”

“I guess then that you’re not a big fan of rap music,” I offer.

“My whole feeling about that is that for those who like it fine. But for me, it’s not that hip. I don’t see how some people rhyming in iambic pentameter can be extremely hip, but I’m not against it. I think it’s hipper than rock ‘n’ roll. I will say that. I think it’s more creative. Even when they use sampling songs. I think the dance element of it is definitely more creative. That’s my true feeling about it. In the context of popular music, I’m not going to disrespect it.”

In England, jazz is also enjoying a revival, only there it’s pan of the club scene, with musicians like Courtney Pine combining their jazz skill with Acid House, world beat and other genres to derive a hot new dance sound. Does any of that appeal to Marsalis?

“I would love to see people dancing to jazz. I would love that. But I’m not willing to embrace new cliches for that.”

by David Hershkovits

Source: PAPER Magazine