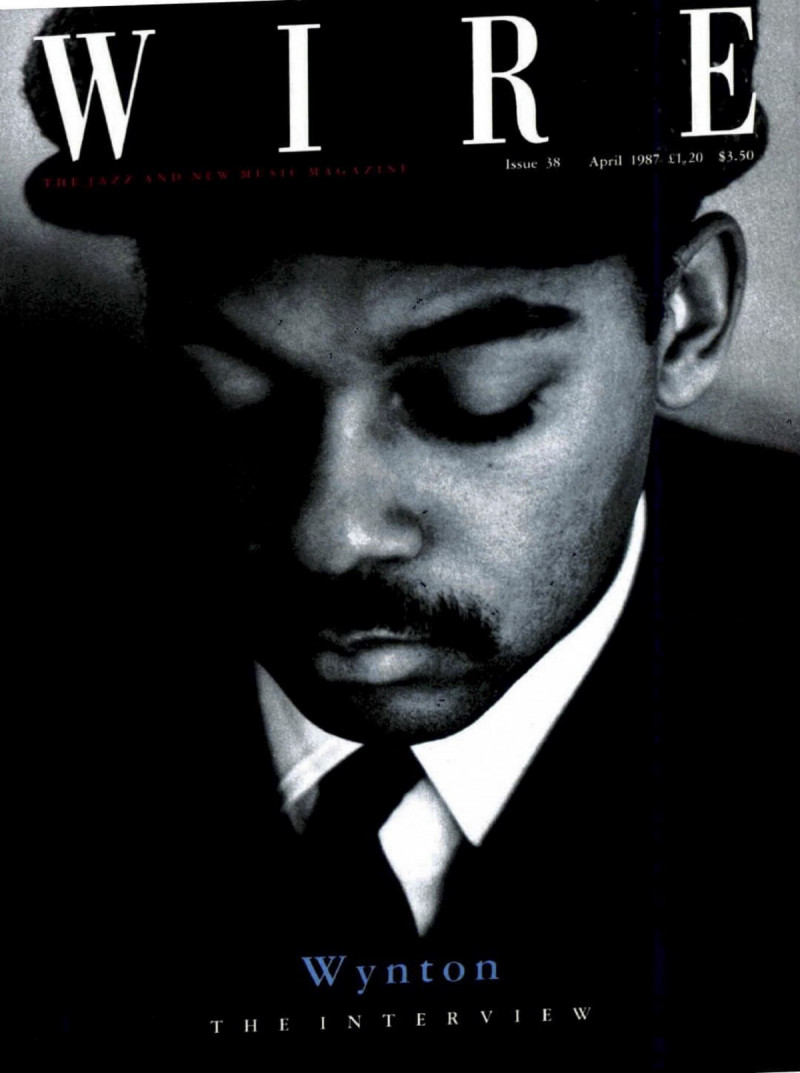

Diligence. The most celebrated figure of new jazz speaks his mind: on journalists, money and soul… and Monk, Duke and Clifford

The WIRE April 1987 (cover photo by Anton Corbijn)

It’s beginning to get like a smokescreen with all this stuff. I wanted to hear a trumpeter, playing jazz and classical music, a great trumpeter, and these days I Seem to be getting a man who talks up a fearsome polemical storm and has his playing shuttled off to some sideline where critics can take it or leave it. How often do we get to hear you now? Where are the records? Why is J Mood a year old before it comes out?

“I have two records in the can, finished. My records come out a year after I make them and there’s nothing I can do about that. I’m going back into the studio in April, after I make this classical record, and I’m going to do two more jazz records this year. And another classical record. I did three last year. One of them is a double LP, one’s a live album, one’s an album of standards, ‘Caravan’, ‘The Song Is You’, ‘April In Paris’.”

Well, that’s a good answer. But every 1ime this name Marsalis comes up now, so do somebody’s hackles. A long time ago (Wire 20) I wrote about how the famous brothers were raising the whole nature of the conversation. Now it’s getting to the point where the conversation’s outplaying the music. It seems as though people are coming to you and prodding out a scream of quotable quotes, of excellent copy, that puts you on a statesmanlike plateau and demands the most magnificent playing to back it up. And, as you say, most of those people probably have no idea what you’re doing anyway, they’ve probably never heard Clifford Brown or Clark Terry. So you punish them. But where is all this leading? Why is a trumpet player doing this? And what use is agony to anybody?

“The first thing is, if I sit up all night every night thinking about something … I lived my whole life the way I lived it, the experiences that you don’t know, you don’t know me, I don’t know you. So, I have to sit down and try and tell you what I’m thinking about. The way you hear it isn’t the way you understand it. The ear you hear it with isn’t … I can think about things that people cold me chat I didn’t hear, because I hadn’t developed to the point of hearing them, properly. In the right context.

“So it’s difficult for people in the media and journalists to hear the thoughts of somebody who’s thinking about something they don’t think about, and try and capture that correctly. They have a difficult job. And it’s taken me a long time to understand that.

“That’s why I tend to be misquoted, because they assign their version of your personality to the public. That’s not good. The best thing with music is not to say anything because you can’t get anything across in ten paragraphs. You sound like you’re preaching. And you have to say I, I, I all the time … it obscures the issues. And the issue is music. The music is so much greater than any individual.”

Yes, and we telescope it all into a “he said, smiling” journalism. It’s hard for us to avoid the I-I-I approach as well. So let’s if we can through this piece without any of that shit.

PERHAPS THE LIFE and sting of this music comes from its tension between the theory and the practice. It seems encouraging that there are so many scholarly young musicians who want to play.

“They will play”. They are playing. Theorising, strategising – that’s cool. But strategy must be served by action. That’s why I liked this group I saw last night, The Jazz Warriors. They were playing, not at home talking. They have a wide range of stuff and they’re playing gigs. In front of people.

“I want to work with other people. Like this record I just did with the English Chamber Orchestra, I had a lot of fun working with them. Great sounds, real nice people. But I’d like to work with a lot of other jazz musicians.”

Are they always asking you?

“Not really.”

Why’s that?

“I don’t know.”

Do you feel isolated?

“Not really. I go down to the Vanguard sometimes and sit in. Frank Morgan, Charlie Rouse, Kenny Barron, all those cats. Then maybe Ornette Coleman, Sonny Rollins, Joe Henderson. I will. I’ll just have to wait till my my playing’s on a certain level before I approach them.”

Isn’t it on that level now?

“No. It takes a long time, you know. It takes a long time. A long time.”

You said that five years ago.

“Five years is not a long time.”

IT COULD BE. And much has been accomplished in five years. The elegance and wisdom of J Mood is not something that could be as confidently measured from your playing of 1982, in that remarkable season at Scott’s.

“Definitely not. But that record’s a year old. We’ve developed a lot of that stuff since then. On J Mood I was trying to slow it down, play blues. That kind of got lost in my generation. Nobody was playing the blues, really, when I was coming up. The generation of musicians right above you have the most influence and I used to think, now people don’t play like that. That was just a time thing. I’d think, oh, that’s just how they played in the 40s and 5Os, now you have to crowd-please. I didn’t know. In New Orleans, I didn’t get to hear too many people. If I’d heard more people, I wouldn’t have as provincial an attitude as I had.”

One never thinks of the trumpet now as ‘provincial’. The hallmarks of your style are all metropolitan: poise, sophistication, urbanity. It’s not mystifying to hear it called clinical or conservative – we’ve been through all of that – because it can be easy to misunderstand the time, miss the use of rests, ignore the subtleties of intonation and colour.

“That’s because I wear round glasses and suits. You have to fall into a noble savage type of thing.”

I suppose we’ve been here before too, but its worth underlining.

“That’s what they tried to reduce Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington to, but their music wouldn’t sustain that. Duke Ellington came under a lot of fire because his music was refined. When people said his music sounded like Delius, he had to go and get their records to hear what he sounded like. Because he had refinement. It’s viewed as something that jazz musicians didn’t need.

“When Louis Armstrong played with the greatest fire and imagination and power and soul, you have to realise that it was a refinement of the modern style. It wasn’t something that he rolled out of bed and picked up his cornet and played, in what they call a ‘dirty fashion’. From his perspective that’s not what it was. It was stylistically correct. And he expanded on the style, too.

Think about time for a moment. Do you feel the passing of time, the passing of bars, as you play?

“No. Beats, different measures of time, 3/4, 5/4, 6/4 … you don’t really think about it like that. The most important thing in music is the tutoring of ear. If you can hear it, it’s not something you can express verbally. If you could, you wouldn’t need music. When you hear better, you can play with more of a sense of urgency, and also play more relaxed. You hear how many beats are passing inside the music but you don’t say – this is four beats.

“There are many things to be done. Diligence is the key. A greater understanding of music.”

THERE IS NO greater love. Although there are many arts to devote it to. Can music be entirely self-centred? Do you bring other things to bear on it?

“All the arts are inter-related. They all function and have a plane of understanding and vision. The main thing they all have io common is a history that weighs on everybody, that forces the level up. If you don’t know how to deal with history, then everything’s reduced to the level of what your personal vision is.

“I think about the other arts, I’ve been checking out a lot of painting. I like cubist painting, it’s interesting. A lot of Schoenberg’s music was like African music, rhythmically, and I think he got that idea from checking Picasso. People like Van Gogh … I don’t like to delineate into schools, but people who could translate a personal vision precisely on to canvas.

If a painter organises the light instead of the darkness on a canvas, then that’s like Monk, organising rests. Like Monk on Duke’s ‘I Let A Song Go Out Of My Heart’, that’s a great solo (hums it). Know what I mean, a phrase like that? He was hearing space a certain way.

“There’s so many people that are so hip in so many areas of the arts. You can just spend your whole life exploring what they did. You get caught up in that, you’ll never find out what you’re trying to do. Matisse, colour. Being able to translate into the idiom. Study and observation. Discipline.”

How about freedom?

“Freedom comes from knowledge. Ignorance is bondage. In contemporary terms that gets confused. There was no freer person in the world than Charlie Parker or Monk. When you know that much, how can you not be free They weren’t natural geniuses. They had a high level of aptitude.

The Creator endowed them with that, but I know 3O or 40 musicians with a high level of talent and they’re not geniuses. You realise how many nights Louis Armstrong played the trumpet, how many players he’d listened to, how many high Cs he’d hit by the time he was 27 years old? Millions. Millions.”

The component. What separates them out?

“A high level of aptitude. A high level of dedication to the craft. And powers of observation that are unusual. Maybe that’s the most important thing. The world can be viewed from so many angles. Monk had another vision of the world. But his credo was, always know. Don’t speculate “

“There’s a good quote in the bible . Proverbs. – I don’t know the exact quote, but it’s ‘the soul that is without knowledge’.

It’s interesting because they use those words together. In jazz, people try and separate them. That noble savage conception.”

IT’S THIS OTHER stuff that keeps intruding. When you’re an eloquent. perceptive man, it’s difficult to avoid taking up the cudgels. You mention Miles and Lester Young, men who refused to follow their immediate role models, Dizzy and Hawkins. By returning to what some call a “60s Miles Davis” method, isn’t that what you did?

“I’m not innovative. I’m still trying to learn the basics of the craft of our music.”

There are ways and ways to innovate

“The thing is to be comprehensive. That’s why I liked The Jazz Warriors. They used a lot of different grooves.”

But you’d never play in a context like that.

“Probably because I couldn’t, bot I sill like it. You can’t limit your resources to one thing. The more things you have to deal with … you can find every groove imaginable on a Duke Ellington album.”

I was just listening to one of his Reprise records, Afro-Bossa.

“Oh. that’s a great record! I just got that and I listen to it every day. He uses a small amount of material there but … (scats most of the themes). From there to a bolero, a cowbell-type groove – that’s a great record.”

You have a good memory for music.

“Well, I listen to music all the time.”

If I played you something, would you be able to play it back to me?

“Depends on what it was. I’m tying to develop that to a higher level”

ARE YOU MAKING a lot of money?

“Why are you asking me a question like that? Compared to what’s being made, no. Who cares? It’s not important. It won’t do anybody else any good.

“If you go into the field to make money, you can be manipulated by people with money. To do stuff against the interest of music, but to make some money, That’s not a good position for a musician. You can’t be amoral, because it’ll show in your form.”

Some might say that you’re speaking from a position of unusually maximised options. The jazz, the classical music, the corporate faith of Columbia; the media attention which, no matter how confining, ensures tickets and record sales. But this bottom line, the music, is always being served.

It is a standard, an example. And it helps to perhaps – impose an earthly setting on a musical frame of mind that is sometimes chillingly superhuman, or even selfless. In the same way that Louis Armstrong’s records of the 30s could sound indestructible and perfect, so some of this Marsalis diligence and infinite craft can be intimidating. The striving after an ever finer point.

“What you strive for is to play with clarity and directness, like Clifford Brown. I don’t know how much money Clifford made but he sure could play. He died when he was 25, and it was a real tragedy. One cat like him could’ve been a remedy to a lot of the clichés that’ve been spread. He didn’t drink or smoke or even curse. He practised his horn. He could swing and he had a big sound. We needed more people like him.

I guess we still do.

“Like Clifford Brown? We’ll take as many of those as we can!”

Can NON MUSICIANS grasp what you’re doing?

“They know. People know. They want more music that sounds good. When you create something that’s really hip, they know.”

In this case, we should know about you.

by Richard Cook

Source: THE WIRE