Bandstand Democracy - Downbeat December 2008

The score is in 4/4,” said Wynton Marsalis as he shifted his feet in time to the accented triplets that seem never to stop running through his head. He was simultaneously in the midst of a rehearsal with his orchestra and Ahmad Jamal for the Jazz at Lincoln Center season program opener, and a standing chess game with his onstage wingman, saxophonist Walter Blanding, Jr., which has been four years in the making.

“Lots of decisions happening here, lots of decisions,” he said, his voice echoing in the wood-paneled rehearsal hall like an “airball” chant during a basketball game. In an extended period of quiet, Marsalis clapped out a rhythm. Then, with nine black and nine white pieces still standing on the chess board, Marsalis and Blanding put down the game. Marsalis took a seat in the back row as Jamal resumed running the rehearsal. It was time to get back to work.

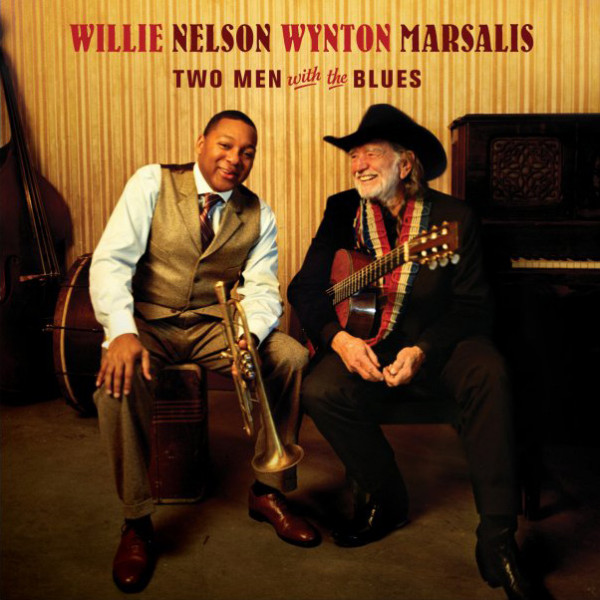

Virtually everything Marsalis does seems to come out of what his long- time colleague in the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra Joe Temperley called a “sense of democracy.” Marsalis’ latest release, Two Men With The Blues (Blue Note), a live album recorded with Willie Nelson at J@LC’s intimate Allen Room, underscores the foundations of blues rhythms in American music, whether the end result is classified as country or jazz. Marsalis composes and arranges with his band’s individual skills in mind. And for decades, he has espoused the concept “all jazz is now,” an idea that plays an important role in the new book he wrote with Geoffrey Ward, Moving To Higher Ground: How Jazz Can Change Your Life (Random House), and in the programming he oversees as artistic director of the most prominent jazz venue in the world.

“Twenty-two years ago, he persuaded Lincoln Center to put on three concerts and a classical jazz series,” said J@LC Executive Director Adrian Ellis. “I don’t know the extent to which the longer-term goal was clear, but it’s a linear progression to adapt to an organization like that and now the next chapter.”

In his early 20s, Marsalis was a more controversial figure, and some of the things he said at that time (he has admitted he would sometimes say things he knew would incite the press) are still quoted back to him all these years later. But then, as now, his agenda has remained intact: to swing and help more people in this country hear the music that is part of its history.

“For all of Wynton’s reputed combativeness, you don’t achieve things like he has if you’re a solo prima donna,” Ellis said. “You can only make those things work through creating effective coalitions of different sorts of people. He has managed to mobilize a whole gang.”

The way he’s done that is not by fighting, but by uniting them. Band members and staff stay together on the road. All band members discuss the situation together before a new member comes into the orchestra. Artists like reed player Ted Nash share the duties bestowed on the orchestra as a whole, teaching appreciation courses at J@LC and penning their own works for the orchestra.

Marsalis relies on a democratic ethic when it comes to the development of his music, too. “I never try and divorce myself from me,” he said. But he surrounds himself with players who understand how to wrap the history of his musical ideas into the present and future. “On my first record, Father Time, we have an African 6/8 rhythm. We put that 6/8 rhythm on the first track of From The Plantation To The Penitentiary. It goes into four and then uses all the kinds of time changes that we’ve used before. All the musicians who play know the music of the musicians that came before them [in the band].”

Two Men With The Blues and the DVD about the development of that performance use history in a similar way. As Marsalis explains in the film, n underlying rhythmic connection exists between country music, blues and jazz, and working with Nelson was a natural choice. “His phrasing is free,” Marsalis said. “There is a lot of freedom in his phrasing. So we’re used to that and it’s a lot of fun to play with him.”

The album, which debuted at No. 20 on the Billboard 200—making it the highest-charting album of Marsalis’ career—is another part of the lin- ear progression he has been working toward for two-and-a-half decades. The film explicates some of the more technical aspects of the music, and recruiting Nelson probably helped bring a few new ears to the music.

The 2008–’09 J@LC season, which Marsalis and his programming staff booked years ago (they are currently about five years ahead of the game), continues in that vein. Jamal opened the season in September. “We’re also hosting the Clayton–Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, in the old style of big bands when they would get together,” Marsalis said. “And we’re playing the music of Monk, and writing new arrangements for a lot of his music. If you look across the season, you’ll see we do some things that are from different eras of jazz. We write all new arrangements for them, and we address all aspects of the language. We have a saying that all jazz is modern and that’s what we live by.”

Other elements of the program build on that idea by giving listeners new access points for the music, like a 50th anniversary celebration of Kind Of Blue and Giant Steps that features Take 6 as the musical directors.

“We can’t re-create an album, so the thing we try to do is draw attention to the album, and speak of some of the implications in the album and give us a way to hear the achievement of the music on the album in a different light,” Marsalis said. “Trying to re-create is a waste of time. We always try to figure out how to come up with a show that will be good, not boring for the audience and will allow musicians to use their different techniques to illuminate some of the aspects of the music on that album or show.”

Marsalis’ new book takes that familiar idea and shows how the musical legacies of the greatest players espouse lessons that can be applied to life as well. He discusses the importance of recognizing what sets you apart and bringing that to the fore instead of trying to be more like others. He talks about John Coltrane’s perseverance, and he discusses how an obsessive version thereof can be dangerous. He looks across America and across a swath of history and explicates in direct, specific terms why so much of what he sees in jazz has to do with life in general.

“This is the future and the past at once, that is what the present is,” he said. “When I said, ‘all of history is now,’ I meant all of it. Not just Bird. Right now is now, too. So the desire to script that which is away from what is becoming, that is the thing that I am not a fan of. Take them all with you, you don’t need to leave anybody behind. You don’t need to leave your great grandma behind. You don’t have to leave your newborn baby behind.”

The book came together because of Marsalis’ friendship with co- author Ward, a historian who learned to retool his assessment of some aspects of history from Marsalis.

“I’m a zealous believer in the power of jazz to unite people,” Ward said. “Wynton wants Americans to understand the music they ought to understand. [Jazz is] who we are and who we will be if things work out right.”

While promoting the new book, album and season, Marsalis has also been working on material for a new album, She And He, due out next spring. Based on an original poem, the album deals with numbers. All the songs are in three, which speaks to the lesson being taught in the poem— the importance of the notion of ourselves and the additional importance of the entity that is “us.” The new album exemplifies Marsalis’ group-centric thinking and his interest in how music can underscore some of the most important aspects of being human.

“There is an identity in our music, and I like that identity,” Marsalis said. He paused and switched back to his pronoun of choice to speak from the perspective of the band. “We function in both arenas: We love to do new things around the world but we love being ourselves. And we don’t know if we’re going to find the most modern version of ourselves in the image of somebody else.”

By Jennifer Odell

Source: Downbeat (December 2008)