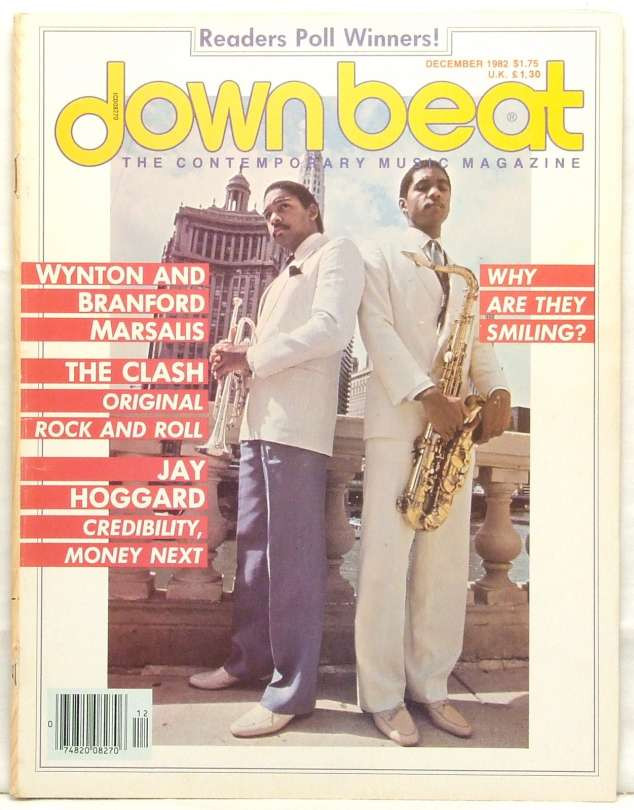

A Common Understanding (Wynton and Branford Marsalis interview): Downbeat December 1982

Downbeat (December 1982 cover)

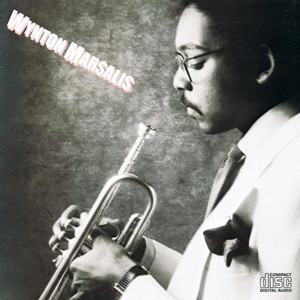

Nineteen eighty-two was the year of Wynton Marsalis – down beat readers crowned him Jazz Musician of the Year; his debut LP copped Jazz Album of the Year honors; and he was named No. 1 Trumpet (handily defeating Miles in each category). In 1980 the New Orleans-bred brassman first stirred waves of critical praise with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers; by the summer of ’81 (with a CBS contract under his arm), he was honing his chops with the VSOP of Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams. By early ’82 Wynton Marsalis was topping the jau charts; Fathers And Sons-one side featuring Wynton, brother Branford on sax, and father Ellis on piano-soon followed (both remain charted to this day), as did whistle-stop tours with his own quintet (Wynton, Branford, pianist Kenny Kirkland, bassist Phil Bowler, drummer Jeff Watts). Now at only age 21, Wynton is on top, and rapidly rising 22-year-old Branford has been signed by CBS on his own.

A. James Liska: Let’s start by talking about the quintet-the Wynton Marsalis Quintet.

Branford Marsalis: That’s what they call it.

Wynton Marsalis: When he gets his band, it’ll be called the Branford Marsalis Quartet.

AJL: Are you going to play in his band?

WM: No-0-0-0.

BM: He’s barred. Let’s face it, when you get a personality as strong as his in a band, particularly playing trumpet and with all the coverage, it would become the Wynton Marsalis Quintet.

AJL: Even though it would be your band?

BM: That’s what it would be.

AJL: Is that a reflection on your leadership abilities as well as your personality?

BM: We’re talking from a visual standpoint. When people come to see the band, the whole image would be like if Miles started playing with somebody else’s band. You can’t picture Miles as a sideman at any time.

WM: Co-op music very seldom works-the type of music in which everybody has an equal position in deciding the musical direction of the band. I mean, somebody has to be the leader.

BM: Everybody else has to follow.

WM: The thing is though, when you lead a band, you don’t lead a band by telling everybody what to do. That’s a distortion that I think a lot of people get by watching bands. Nobody has ever had a great band in which they had to tell all the guys what to do. What you do is hire the cats who can play well enough to tell you what to do. But you have to make it seem like you’re telling them. It’s psychological; you have to be in charge of it, but you don’t want to be in charge of it. AJL: Then the role of the leader is …

WM: What I’m saying is that the direction of the band is formed by the band, but it goes through one person: the leader. If you’re a leader, you lead naturally, automatically.

AJL: From the co-op perspective then, don’t all-star sessions gener-ally work?

WM: They don’t work as well as an organized band. Sometimes, something exciting can come about. But that’s rare because jazz – I hate to use that word – group improvisation is something that has to be developed over years of playing together or, at least, from a common understanding. The reason that these all-star things can work so well is that everybody has a common ground. It’s when you lump people from all different forms of music together that it sounds like total shit.

BM: Nowadays, sometimes the ego thing is so strong it’s like, well, I’ve actually seen jam sessions where cats would say “I’m not going on the stage first. You play the first solo.” As soon as that starts, the music is over. I sat and watched, for over two hours, a battle of egos like that. It was the worst musical experience I ever had. The people were going crazy because there were all these great jazz musicians on the stage. If they only knew what they were listening to and what was really going on. It hurt me man. I think that’s the major problem with all-star thing because when you have a group, you have one leader and some followers who maybe can lead but they followers nonetheless. The position of the follower is always underrated. A band has to have great followers; you can’t have five great leaders.

AJL: The too-many-chiefs, not-enough-Indians syndrome?

BM: No Indians.

WM: The thing that makes it most intricate is that you have to realize that when you lead a band, you’re leading a group of cats that know more about everything they do than you know. That’s the one great thing I learned from Art Blakey. He’s one of the greatest leaders in the world, and the reason is that he doesn’t try to pretend that he knows stuff that he doesn’t know. But he’s the leader of the band, and when you are in his band, you never get the impression that you’re leading it. I knew all the time that he was the leader. He didn’t have to tell me that. He’s that kind of man.

AJL: And that wasn’t ego-inspired?

WM: His stuff has nothing whatsoever to do with ego, man. He’s just a great leader. Of course, he’s been doing it for so long. But that’s true with a lot of different people. When Miles had the band with Herbie and them, do you think he told them what to do? He was struggling to figure out what they were doing. He had never had cats play like that, but he was wise enough to let them decide what was going to happen. He didn’t make them play just what he could play. But they always knew he was the leader, and you can listen to the records and know he’s the leader.

AJL: Is there a like situation in your own quintet? Are the guys telling you what to do?

WM: There are certain things that they do that I don’t know what it is, that I have to ask about. You know, like, what was that you played? What is that? What chord is that? What voicing? What’s the best choice of this? That’s what you have to do to learn. The hardest thing about being a leader is that you have to lead a group of cats who might know more than you know.

AJL: Then why are you the leader if you know so little?

BM: (laughing) He must know enough.

AJL: Are you a great follower?

BM: I’m a great follower.

AJL: Do you think you’ll be a great leader?

BM: Great leaders were usually great followers. You have to be a follower before you can lead. That’s what I’ve always thought. I’m learning a lot now, particularly economically, you know, business. He’s setting the path for me, and I’m not going to have to make the same mistakes and go through the same crap that he’s going through. While he’s going through it, I’m sitting back observing, watching everything that they’re trying to do to him.

AJL: Who are they?

BM: Record companies, agents, managers, the whole works. The hassles with the music, the gigs, riders in additions to contracts.

AJL: So Wynton deals with it and you have the benefit …

BM: Sitting around and learning. It’s a drag that it had to be like that because all that pressure was thrown on him. People are always asking the classic dumb question: How does it feel to have a brother getting all that attention and blah, blah, blah? They obviously have no idea what all that shit entails. I sit down and watch him doing all of this and say, “Yeah, great … somebody’s gotta be in the hotseat. Better him than me.”

AJL: Is Wynton more able to deal with pressures than you?

BM: He thrives better under pressure than I do. If I had to deal with it, I’d deal with it. But he functions best under pressure. I function best when people leave me the hell alone and I don ‘I have to deal with a lot of crap. If I have to deal with it, I’ll deal with it. But, like, he went to the hardest high school to go to.

AJL: By choice?

BM: By choice. He could have gone to the middle-of-the-road one like I did. I went to that one which meant I didn’t have to study. He went to the hardest one. I’ll admit it – I’m the classic lazy cat. I didn’t want to be bothered; I didn’t want to practice. I just wanted to exist. So I didn’t practice. I played in a funk band and had a great time. When it was time to go to college, I went to the easiest one I could go to with the best teacher for music. But I really wasn’t serious about music.

But back to the original subject; Wynton played classical music because someone told him black cats couldn’t play classical music. The first time he went out there every one of the oboe players played the notes kind of out of tune, just to throw him off. He thrives best under that kind of stuff. If it were all relaxed and they just said, “Anything you want, man,” I think he’d be kind of shaky. When people tell him “No,” that’s when he’s at his best. So all the pressure’s on him. Good. When I come around and get my band, there shouldn’t be that much pressure.

AJL: Coming from the same family, being close brothers, how did you end up so different?

WM: My mother. My mother’s a great woman. She treats everybody the same, so we’re all different. When you treat everybody the same way and don’t tamper with the way you treat them in accordance to their personality, then they act differently. They develop into their own person. Like Branford and me, we’re totally different. BM: Radically different.

AJL: Yet you appear to be best of friends.

WM: Well, we have our things. BM: Appearances can be deceiving.

WM: All my brothers … we grew up living in the same room, you know? He was always my boy, though. Like, I could always talk to him.

AJL: You two are the closest in age?

BM: We’re 13 months apart.

WM: I always took my other brothers for granted. When Branford went away to college and I was stilfin high school, that’s when I missed him. But we used to argue all the time. We think totally different. Anything I would say, he’d say just the opposite.

AJL: Just to be obstinate?

WM: Just to say it.

BM: It wasn’t just to say it. It was because I didn’t agree.

WM: Nothing I say he agrees with.

BM: Some things I agree with.

AJL: Musically, did you agree?

BM: No.

AJL: Still?

WM: No.

BM: Know what we agree on? I’ve thought about this a lot. I think we agree on the final objective. I think the common goal is there, but the route to achieve the common goal is totally different.

WM: Totally.

BM: It’s like catching the “E” and the “F” train. They both come from Queens to New York, and they both meet at West 4th Street, but one comes down Sixth Avenue and one comes down Eighth Avenue. WM: The way I think the shit should be done, he doesn’t.

AJL: How do you work so well together?

BM: It’s simple: he’s the leader.

WM: Everybody thinks it’s hard because he’s my older brother. If we weren’t brothers, if he was just another cat, nobody’d think anything of it. People are always going to try to put us together as brothers, and I don’t want that. I tell people all the time that the reason Branford’s in my band is because I can’t find anybody that plays better than him.

AJL: Are you looking?

WM: No. (laughs) But if they come …

BM: Bye-bye me.

WM: I don’t have him in the band because he’s my brother. I use him because I like the way he plays. Shit is very cut and dried with me: either you can play, or you can’t; either you know what you’re doing, or you don’t. I use him because he’s bad. Period.

BM: I’ve always believed that when you’re dealing with certain things, there are businesses and friendships. The two should never meet. The reason we get along so well is that when we play music, it’s the Wynton Marsalis Quintet, and I’m in the band. When we’re in this house, it’s my brother, Wynton.

WM: What you have to realize is that everybody in the band is bad. That’s what nobody wants to admit. They’ll say “Branford can play” or “Wynton’s alright.” Everybody in the band is bad. Jeff Watts knows as much as anybody about the music. Kenny Kirkland. Phil Bowler. These cats know about the music. It’s not like one cat can play and he towers over everybody els~ in the band. People think that’s how bands run. In this band, all of the cats have the capabilities. And when they do interviews . . What about Kenny? Why doesn’t he get the publicity? What about Phil? Why doesn’t Jeff get interviewed? It’s because nobody’s said that he’s good yet.

AJL: Where did you find Jeff Watts, the drummer?

WM: Branford knew him from Boston. BM: I knew he wa~ bad because nobody liked him. When I heard that, I couldn’t wait to hear him.

AJL: Did you first hear him with a group?

BM: No. It’s hard to get a group in Boston, but we had the privilege of having ensemble rooms; we’d just sit around and have jam sessions, and everytime he’d play, everybody would get lost. They couldn’t tell where “one” was, and then they’d say, “He’s sad. I can’t hear ‘one.”’

WM: Branford knew him from Boston.

BM: I knew he wa~ bad because nobody liked him. When I heard that, I couldn’t wait to hear him.

AJL: Did you first hear him with a group?

BM: No. It’s hard to get a group in Boston, but we had the privilege of having ensemble rooms; we’d just sit around and have jam sessions, and everytime he’d play, everybody would get lost. They couldn’t tell where “one” was, and then they’d say, “He’s sad. I can’t hear ‘one.”’

WM: He’s conceptually bad.

BM: Then we started hanging out and talking.

WM: He knows a lot of shit, man. He has a concept about the music.

AJL: What about Phil Bowler, the bassist?

WM: He played with Rahsaan [Roland Kirk] a long time.

AJL: How did you find him?

WM: I was playing everybody. Jamil Nasser recommended him. We had tried a lot of different cats. Phil’s got great time, and that allows Jeff to play what he wants. Plus, he has a good knowledge of harmony and rhythmic-derivational things. He plays interesting ostinatos.

AJL: Where did you find Kenny Kirkland?

WM: Everybody knows him. He’s one of the baddest cats playing piano today. You just know about him.

AJL: What’s the most difficult thing about keeping your group together?

WM: Getting gigs. I worked three gigs in May with the band, and those were like one-hour gigs. You’ve got to gig all of the time, but you can’t make money working in the clubs.

AJL: What about the concert hall situation?

AJL: How so?

WM: The music was different in the ’50s and ’60s than it is now. Then you could play popular tunes in the jazz setting and make them sound hip.

AJL: And now?

WM: You can’t do that now because all of the popular tunes are sad pieces of one-chord shit. Today’s pop tunes are sad. Turn on the radio and try to find a pop tune to play with your band. You can’t do it. The melodies are static, the chord changes are just the same senseless stuff repeated over and over again. Back then you could get a pop tune, and people were more willing to come out and see the music because it had more popular elements in it. They could more easily identify with it.

AJL: Have the pop tunes of back then lost their meaning today?

WM: They haven’t lost their meaning, but they’re old. You’ve heard them played so many times by great performers that you don’t want to play them again.

AJL: Any suggestions or solutions?

WM: You can’t do that now because all of the popular tunes are sad pieces of one-chord shit. Today’s pop tunes are sad. Turn on the radio and try to find a pop tune to play with your band. You can’t do it. The melodies are static, the chord changes are just the same senseless stuff repeated over and over again. Back then you could get a pop tune, and people were more willing to come out and see the music because it had more popular elements in it. They could more easily identify with it.

AJL: Have the pop tunes of back then lost their meaning today?

WM: They haven’t lost their meaning, but they’re old. You’ve heard them played so many times by great performers that you don’t want to play them again.

AJL: Any suggestions or solutions?

WM: People say, “Man, you sound like you’re imitating Miles in the ’60s,” or else, “He sounds like he’s imitating Elvin Jones.” So what? You just don’t come up with something new. You have to play through something. The problem with some of the stuff that all the critics think is innovative is that it sounds like European music-European, avant garde, classical 20th century static rhythm music with blues licks in it. And all these cats can say for themselves is “We don’t sound like anybody else.” That doesn’t mean shit. The key is to sound like somebody else, to take what is already there and sound like an extension of that. It’s not to not sound like that. Music has a tradition that you have to understand before you can move to the next step. But that doesn’t mean you have to be a historian.

AJL: Earlier you expressed an aversion to the word “jazz.” Why?

WM: I don’t like it because it’s now taken on the context of being everything. Anything is jazz; everything is jazz. Quincy Jones’ shit is jazz, David Sanborn … that’s not to cut down Quincy or David. I love funk, it’s hip. No problem to it. The thing is, if it’ll sell records to call that stuff jazz, they’ll call it jazz. They call Miles’ stuff jazz. That stuff is not jazz, man. Just because somebody played jazz at one time, that doesn’t mean they’re still playing it. Branford will agree with me.

BM: (laughs) No. I don’t agree.

WM: The thing is, we all get together and we know that this shit is sad, but we’re gonna say it’s good, then everybody agrees. Nobody is strong enough to stand up and say, “Wait, this stuff is bullshit.” Everybody is afraid to peek out from behind the door and say, “C’mon man.” Everybody wants to say everything is cool.

AJL: Do you have as strong a feeling to maintain the standards?

BM: Yes. Even stronger in some ways. I just don’t talk about it as much. A lot of the music he doesn’t like, I like.

AJL: Like what?

BM: Like everything.

WM: Like what? BM: Like Mahavishnu. A lot of the fusion stuff. WM: I don’t dislike that.

BM: It’s not that you dislike it, it’s that you prefer not to listen to it.

WM: That’s true.

BM: I don’t consider it being more open; it’s just that he’s kind of set in his wa.ys. What I feel strongly about is the way the business has come into the music. Everything has become Los Angeles – everything is great and everY,thing is beautiful. It’s kind of tired. Cats come up to me and say: “What do you think of Spyro Gyra?” And I say: “I don’t.” That’s not an insult to Spyro Gyra. I just don’t like it when people call it jazz when it’s not.

AJL: Any advice for young players?

WM: Avoid roots. BM: I think the basis of the whole thing is the bass player. The rhythm section is very important. If I’ve got a sad rhythm section, I’m in trouble.

WM: Listen to the music. High schools all over the country should have programs where the kids can listen to the music. Schools should have the records, and the students should be required to listen to them all, not just Buddy Rich and Maynard Ferguson. They should listen to Parker and Coltrane and some of the more creative cats. That should be a required thing. Jazz shouldn’t be taught like a course. The students should know more than a couple of bebop licks and some progressions.

BM: Never play what you practice; never write down your own solos – a classic waste of time unless you’re practicing ear training.

WM: You should learn a solo off a record, but don’t transcribe it. It doesn’t make sense to transcribe a solo.

BM: You’re not learning it then, you’re reading it.

WM: And learn a solo to get to what you want to do. You don’t learn a solo to play that solo.

BM: What people don’t realize is that what a soloist plays is a direct result of what’s happening on the bandstand.

WM: You should learn all of the parts-the bass, the piano, the drums-everything.

BM: Right.

WM: And learn a solo to get to what you want to do. You don’t learn a solo to play that solo.

BM: What people don’t realize is that what a soloist plays is a direct result of what’s happening on the bandstand. WM: You should learn all of the parts-the bass, the piano, the drums-everything.

BM: Right.

by A. James Liska

Source: Downbeat