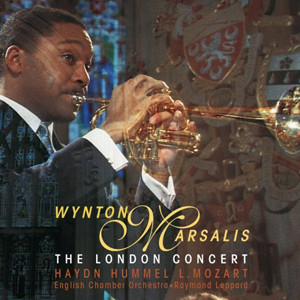

The London Concert

Whether in jazz or classical music, great musicians must return again and again to the landmark compositions in their fields. Wynton’s first recordings of the trumpet concertos by Joseph Haydn, Leopold Mozart, Johann Friedrich Fasch, and Johann Nepomuk Hummell, made when he was only twenty years old, won instant recognition as the work of a new classical virtuoso and were honored with two Grammy Awards. Twelve years later he returns to the same pieces in interpretations that do not replace, but rather form a fascinating counterpart to, those on his first classical CDs.

Recorded at St. Giles’ Church, Cripplegate, London – February 17-19-23, 1993

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis with The English Chamber Orchestra |

|---|---|

| Release Date | November 8th, 1994 |

| Recording Date | February 17-19-23, 1993 |

| Record Label | Sony Classical / Legacy |

| Catalogue Number | SK 93084 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download, VHS |

| Genre | Classical Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Franz Joseph Haydn - Concerto for Trumpet and Orchestra in E-flat Major, Hob. VIIe:1 – (1732-1809) | ||

| I. Allegro | 6:51 | Play |

| II: Andante | 3:11 | Play |

| III. Finale (Allegro) | 4:33 | Play |

| Leopold Mozart - Concerto for Trumpet and Orchestra in D Major – (1719-1787) | ||

| I. Adagio | 5:34 | Play |

| II. Allegro moderato | 3:25 | Play |

| Johann Friedrich Fasch – Concerto for Trumpet, 2 Oboes, Strings and Continuo in D Major – (1688-1758) | ||

| I. Allegro | 2:23 | Play |

| II. Largo | 0:59 | Play |

| III. Allegro (moderato) | 2:50 | Play |

| Johann Nepomuk Hummel - Concerto for Trumpet and Orchestra in E Major – (1778-1837) | ||

| I. Allegro con spirito | 9:55 | Play |

| II. Andante | 5:15 | Play |

| III. Rondeau (allegro molto) | 3:35 | Play |

| BONUS TRACKS | ||

| Michael Haydn - Concerto for Trumpet and Orchestra in D Major – (1737-1806) | ||

| I. Adagio | 5:57 | Play |

| II. Allegro | 2:54 | Play |

| Antonio Vivaldi - Concerto for Two Trumpets and Strings in C Major, RV 537 – (1685-1750) | ||

| I. Allegro | 3:07 | Play |

| II. Largo | 0:58 | Play |

| III. Allegro | 3:20 | Play |

| Johann Sebastian Bach - Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major, BWV 1047 – (1685-1750) | ||

| I. [ - ] | 5:23 | Play |

| II. Andante | 4:05 | Play |

| III. Allegro assai | 3:02 | Play |

Liner Notes

MARK SWED: Musicians, over time, evolve, change, grow. When you recorded the Haydn, Hummel and Leopold Mozart concertos a dozen years ago at the young age of twenty, you received glorious reviews and the Grammy Award for Best Classical Soloist with Orchestra, followed the next year by a Grammy for another concerto recording that included the Fasch (and in both years you won a Grammy for Jazz – an unprecedented combination of recognition both as a classical and jazz master). Now you are one of America’s most celebrated musicians, and a dominant presence in jazz – as trumpeter, band leader, composer, artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, taste maker, and educator. You also are now an experienced classical musician. How has your approach to these works changed over the years?

WYNTON MARSALIS: When I first recorded these concertos, I had performed the Haydn maybe three or four times and the Hummel once, in high school. I hadn’t really considered playing classical music because at that time I had just started my own band to play jazz music. Recording these concertos seemed like a novelty. This time I approached these works with the experience of having performed with different orchestras, and, though I hadn’t played these concertos for four years, I’ve had the opportunity to study them, to reflect on them, and to have taught these pieces many times to students all over the world.

MS: Still, given that your life is, and always has been, lived mainly in jazz, do you consider these concertos, in any way, a part of your heritage growing up in a jazz family in New Orleans? Can you speak about what the works mean to you personally as a performer?

WM: The Haydn is definitely part of my heritage as a trumpet player. It is a part of the heritage of all trumpeters. It’s the first piece in which the trumpet plays lyrical passages in the middle register. It introduced new aspects to the trumpeter’s personality which still resonate.

As a student, at age 12 or 13, I first heard recordings of it. So part of my schooling included the Haydn Trumpet Concerto. The Leopold Mozart I first remember from about the same time. I heard Maurice André play it. And the Hummel, too.

So I don’t care if Haydn was from Austria and I’m from New Orleans. That doesn’t mean that things that happened in Austria in 1796 are not brought to bear on my experience as an American in this time.

MS: But what about the style in which you play concertos from the late-18th and early-19th centuries? That’s a big issue these days when period instruments and period practices are so prevalent. Do such considerations seem somehow foreign to you as a jazz musician from New Orleans?

WM: Music was played in a certain way, but we don’t know what it was. And there’s no way for us to know. It’s my personal belief that musicians of Haydn’s time played with a feeling and a style which is gone from the world. It would be an act of mysticism to figure out how they sounded. In the same way, I feel that the music of Haydn’s time had a quality and a sound to it that is like the early New Orleans music. I don’t mean the style. But the early New Orleans music has the sound of people working something out, and I don’t think that people today can get that sound. But we can translate that feeling using today’s musical language.

I try to interpret whatever music I play from a contemporary vantage point, and I try to play it in a clear fashion. I don’t try to impose some modern conception of what that style used to be.

MS: Does your choice of instrument affect your playing, and has that changed over the years?

WM: I play the concertos on the same instruments I played them on ten years ago. But I really don’t care. I try to get the best instrument that I can, but whatever instrument I have to play, I play. Ultimately your sound is just your personality being projected. That’s really your sound. And it’s good not to be tied to an instrument. I’m not against period instruments. The difference between a tube with two holes and a trumpet is not that great. It’s a matter of the mechanization. The sound that you’re going to project comes from you. Everything else is an academic argument. Ask Dave Monette (a custom trumpet maker).

MS: What about cadenzas? Do you ever improvise them?

WM: I did once, but I don’t anymore. To really improvise in a style, you have to feel comfortable with that vocabulary, and I don’t feel comfortable enough to improvise in music of this period. Most of the time when I’m playing I am improvising, so I know what it feels like to be able to create something inside of a language and for it to be consistent. But my concept of improvisation is always group improvisation, so I’m always improvising with someone else, and that’s very different than improvising by yourself.

MS: Does this mean that it requires a completely different way of thinking to go from your jazz septet or a big band to playing classical music with an orchestra?

WM: It’s a completely different way of playing, but it’s not a different way of thinking. You have a theme and how the theme is developed. That’s a basic concept in western music. It only seems different if you insist on thinking about the concertos in relation to jazz. But you don’t do that. For example, we talk every day. But if I give you a book to read, you don’t think, “I wish I were talking.” You read it. That’s the convention of reading: your whole life you’ve read, and you have never thought about improvising while reading.

MS: I’ve always found a concerto a very peculiar form. Just what is the group dynamic supposed to be? Are you part of a group or is there some conflict going on?

WM: A concerto is a battle. It’s also a dialogue. You battle, and you also speak. Let’s take the development section of the [first movement of the] Haydn. You go back and forth between conflicts, and then they get resolved. Haydn alternates orchestra and trumpet, orchestra and trumpet, and they get closer and closer together throughout the development section. Every composer who writes a concerto creates a different type of dialogue. Duke Ellington wrote the song “Concerto for Cootie,” and he goes back and forth, between the band and Cootie Williams, and they come together on the bridge.

MS: How then does the experience of playing dialogues in jazz influence the way you phrase and interact with a classical orchestra?

WM: Just the experience of playing and learning how to play through jazz has an effect. The jazz tradition in the purest sense includes classical music. The development of musicianship in jazz means you learn how to sing; you learn how to swing harder; you interpret the rhythm with intensity; you develop a personal tone and your reflexes become quicker. These are all things that you can use in playing classical music. Since you’re improvising solos constantly in jazz music, you get more of an overall conception of thematic development which can be applied to playing written music. You develop an understanding of the architecture of the pieces.

But I also grew up playing these classical concertos. And when I’m playing them I don’t think about playing jazz. The effects of playing jazz are always present when I play: the interpretation of the rhythm, of trying to swing, of playing with a certain optimism that’s in jazz music.

The advantage of being in jazz is that the jazz musician in the truest sense believes what Louis Armstrong believed, that the power of his music could transform anything it touched into jazz. So traditionally, jazz musicians could be whatever they wanted to be and still be themselves. They didn’t have to say, “Don’t listen to classical music, because that will take you away from your identity.” You can listen to classical music, because you can add that to what you’re doing.

MS: So your concept of tradition is actually to be modern, isn’t it, in that you reject the entire idea of specialization, not only between jazz and classical music, but specialization within those fields as well?

WM: It’s like being at a big banquet. Now, if you want to just sit down where the grapes are and argue about the merit of one grape over another, that’s fine. That means if I want to get some grapes, I can walk over and ask you, who’s been sitting there for 15 years, which is the best grape. And you can tell me that it’s this grape right here. That will save me the trouble of finding it myself. But I might want to go down the whole table. What I don’t like, I won’t eat. But what I like, I’m going to eat.

© 1994 Mark Swed

Credits

Consists of previously released material.

Original Producer: Steven Epstein

Tracks 1-11:

Engineer: Charies Harbutt

Editing Engineer: Steven Deur

Remote Technical Supervisor; Tim Wood

Album Coordinator: Alison Booth

Recorded digitally at St. Giles Church, Cripplegate, London, England, February 17 & 19-23, 1993 (photos from recording session)

Instruments used:

Haydn: Schilke E-flat Trumpet with C-Trumpet Bell

Hummel: Schilke E Trumpet

Mozart & Fasch: Schilke Piccolo Trumpet in A

Tracks 12-16:

Engineers: Bud Graham and Steven Epstein

Overdub Coordinator. Peter Jones

Recorded at St. Barnabas’s Church, London, England, February 2-5 & March 31-April 3, 1987

Trumpet: Schilke Piccolo Trumpet in B-flat-A

Adapted, elaborated and arranged by Raymond Leppard

Tracks 14-16: Wynton Marsalis, Trumpets 1 & 2 (synchronization)

Tracks 17-19:

Recording Engineer: Charles Harbutt

Editing Engineer Dawn Frank

Technician: Tim Wood

Harpsichord continuo: lan Watson; Cello continuo: Charles Tunnell

Recorded at St. Giles Church, Cripplegate, London, England, June 19-23 & 25, 1995

Trumpet: Schilke Piccolo Trumpet

For Masterworks Expanded Edition:

Series Concept: Marc Offenbach

Series Design: Giulio Turturro

DSD Engineer: Todd Whitelock

Original Cover Design: Jo Di Donato

Photography: Page 6, Back Booklet Cover & Inside Tray: Janusz Kawa; Other Photos: Sony Music Archives

Personnel

- Raymond Leppard – conductor

- Anthony Newman – conductor

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Haydn: Concerto for Trumpet and Orchestra in E-flat Major (Allegro) - Wynton Marsalis

-

Videos

Videos

Hummel: Concerto for Trumpet and Orchestra in E Major (Andante) – Wynton Marsalis

-

Videos

Videos

Hummel: Concerto for Trumpet and Orchestra in E Major (Allegro con spirito) – Wynton Marsalis

-

Photo Galleries

Photo Galleries

London Concert, Recording Session

-

Wynton's Blog

Wynton's Blog

This is a story about an exchange I had with Sarah Vaughan when playing with Boston Pops