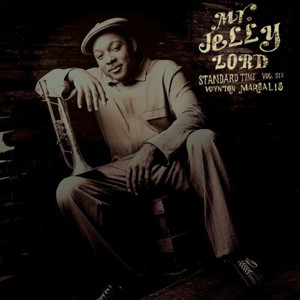

Mr. Jelly Lord - Standard Time Vol. 6

Fifteen classic stomps and blues by Jelly Roll Morton, including “King Porter Stomp” and “The Pearls,” give Wynton the opportunity to demonstrate that the music of this New Orleans jazz pioneer remains as modern as tomorrow. Wynton performs here with fellow New Orleans natives Kent Jordan (flute), Reginald Veal (bass), Herlin Riley (drums), Don Vappie (banjo), and Harry Connick, Jr. (piano). And don’t miss Wynton’s duet with pianist Eric Reed on “Tom Cat Blues,” recorded on the same sort of wax cylinder equipment that Jelly Roll Morton used on his first recordings in the early years of the 20th century.

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Septet |

|---|---|

| Release Date | September 7th, 1999 |

| Recording Date | January 12-13, 1999 |

| Record Label | Columbia |

| Catalogue Number | CK 69872 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Red Hot Peppers | 3:42 | Play |

| New Orleans Bump | 4:36 | Play |

| King Porter Stomp | 3:13 | Play |

| The Pearls | 3:55 | Play |

| Deep Creek | 5:16 | Play |

| Mamanita | 2:51 | Play |

| Sidewalk Blues | 5:14 | Play |

| Jungle Blues | 6:51 | Play |

| Big Lip Blues | 3:20 | Play |

| Dead Man Blues | 4:44 | Play |

| Smokehouse Blues | 4:54 | Play |

| Billy Goat Stomp | 3:02 | Play |

| Courthouse Bump | 3:31 | Play |

| Black Bottom Stomp | 4:23 | Play |

| Tom Cat Blues | 2:14 | Play |

Liner Notes

All Jazz is Modern:

The Music of Mr. Jelly Lord

Of this, his latest effort, Wynton Marsalis says, “I wanted to, once again, reiterate the contemporary power of even the earliest jazz. Jelly Roll Morton’s music proves that all jazz is modern. His music captures the full range of New Orleans life. Jelly Roll Morton’s music, however, still applies to the New Orleans of today. It is dated neither in form nor feeling.”

“In New Orleans, we still play funerals and parades, we still have blues clubs, and we still have the same easy, poetic attitude toward the carnal. We still have the willingness, if the wrong thing is said at the wrong time, to sink all the way back to those ways that underlie the wild side of our reputation. Jelly Roll Morton knew all of that, and the music he wrote and spent so much time meticulously teaching his musicians, has grooves, emotions and forms that exist for the purpose of expressing those powerful New Orleans artistic sensibilities.”

“That is why I have always enjoyed playing Jelly Roll Morton’s music over the last twenty years. It has taught me a great deal about the meaning of jazz and it always refreshes your understanding of how timeless art is. What makes something art is that it’s true for the time in which it existed and remains true in the times that follow. Whenever you endeavor to play the music of Mr. Morton correctly, you discover that what he was doing is just as strong now as it was when he created it. His compositions tell the story of the eternal New Orleans, which is the eternal human story, the timeless thing that jazz musicians express when they master blues and swing.”

“In or out of jazz, there has never been a major composer who was quite like, or even near, Jelly Roll Morton. Morton was something. He had just about every kind of bad quality a human being could have and just about every trait necessary to prove himself a genius. He was a braggart; he was racially prejudiced; he sold poisonous snake oil door to door; he was a pool shark; he was a pimp; he was a sharp shooter, and he was a man who believed in his art as much as any great artist of any idiom has ever believed in the aesthetic form of choice.”

“He was the first who had serious theories about jazz, and all of them were correct. As much of a street thug, hustler, and self-promoter as he might have been, Morton was the initial intellectual to enter the music. His impact was profound, whether it was on those he taught to play as he rambled from state to state or those such as Duke Ellington. All were indelibly touched. Morton understood how form should be manipulated and he recognized the importance of dynamic shifts and improvisations to intensify the quality of compositions. There was a rather direct relationship between his music and his life. Our first great composer of jazz had an epic sense of life. He played in parades, hung out in after-hours joints where the high and the low class gathered to pursue joy. His piano provided the live soundtrack for whorehouse erotic melodramas. He heard the most primitive blues sung by New Orleans dock workers. The worst side of the criminal life was familiar to him and Morton also spoke of women belting out the blues from their doorways. He heard that music of the opera and the symphony and recognized that jazz should contain the best elements of the musical gutbucket as well as the technical penthouse. The mixed parentage of jazz was obvious and it was Morton who recognized the essential significance of riffs and of the Afro-Hispanic rhythms he called “the Spanish tinge.”

Wynton Marsalis, who is easily the most gifted and the most sophisticated musician of his generation, has brought together young musicians to play his music just as someone in the European idiom would bring young musicians together to play the music of the Eighteenth Century, and for the same reason. When you get into the profound, those who started it all or put the first serious refinements on it, or foresaw what could be done by doing everything possible at the time, you not only instruct those performers in ways that will influence whatever they do in whatever style, you also reiterate the fact that in human terms there is no past, only a present when it comes to art. This is what this recording is all about. Here you will witness just how well musician, who have no problems addressing the sweep of their art, perform the work of Jelly Roll Morton. From the clarity of the ensembles to the wring of the group, to the precision, wit, lyricism, and fire of their improvisations, they achieve victories of the very same quality that they do when Marsalis and his players address any kind of jazz, whether basic, in the middle or all the way out of the frontier where blues and swing are given extraordinary reinterpretations. Here, with the same kind of authority Kenneth Branaugh brought to his Henry V. Much Ado About Nothing, and Hamlet, they let us know that old and new are only as meaningful as the material and the artists who give it life or fail to do so. In this case, life brims up out of every note, just as Mr. Jelly Lord intended.

– Stanley Crouch

Credits

On December 6, 1993, Wynton Marsalis, his band, and producer Steve Epstein entered the Thomas Edison Laboratories in West Orange, New Jersey for the purpose of making a record. The result is track number fifteen, “Tom Cat Blues.”

Nearly a century earlier, as we have come to know, the Edison Laboratory was a center of research and experimentation-into the art of capturing musical performances on wax cylinders.

At that time, the wax cylinder record was the predominant format far audio recordings. Pioneer engineers did not use microphones to transfer sound waves via electrical energy InstEad. a cone-shaped recDrding ham tunneled sound waves acoustically to the masters cutting stylus.

Below are producer Steve Epstein’s thoughts regarding the Experience of recording Wynton in this way. His comments are abstracted from an interview appearing in NARAS Journal. Valume 8, Number I.

Wynton has always felt that the really “honest”-sounding recordings were those that artists like Louis Armstrong, and Jelly Roll Morton, and King Oliver did in the early years of jazz. There’s a certain integrity in those recordings. Wynton always harked back to his heroes of those days. While he’s very happy with current recording standards, there is a certain quality that he feels might be missing in modem jazz recordings.

In modern recording, the artist has the option of having [his work] edited. On the other hand, in the days of cylinder recordings, editing was not an option. They would do several complete takes on several cylinders and decide which one to use. But in this situation, with Wynton Marsalis [and Eric Reed] recording on wax cylinder, you have a mixing of two eras. You have contemporary jazz musicians, familiar with contemporary recording techniques, working with equipment that became technically obsolete very long ago. Though with jazz, unlike with classical music, you’re not striving for note perfection. You are striving fora certain feel, a certain musical statement. Any mistakes made here or there are not realty mistakes. They are color.

Going into the room which Edison hadn’t used since the turn of last century, a musty old room off the beaten path, was like stepping into history. We could just sense the vibes; the smell and feel of the place lent itself to the authenticity of what we were attempting, and what I think we captured.

All compositions written by Jelly Roll Morton and published by Edwin H. Morris & Co. Inc. (ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis – trumpet

Eric Lewis – piano

Herlin Riley – drums

Reginald Veal – bass

Wycliffe Gordon – trombone, tuba & trumpet (on “Red Hot Pepper”)

Lucien Barbarin – trombone

Wessell Anderson – alto saxophone

Victor Goines – tenor & soprano saxophones, clarinet

Michael White – clarinet

Donald Vappie – banjo, guitar

Danilo Perez – piano (on “Mamanita”)

Harry Connick, Jr. – piano (on “Billy Goat Stomp”)

Eric Reed – piano (on “Tom Cat Blues”)

Produced by Steve Epstein

Engineered by Todd Whitelock

Technical Supervisor: Mark Betts

Assistant Engineer: Jen Wyler

Stage Assistant: Ron Martinez

Production Coordinator: Dennis Jeter

“Billy Goat Stamp Recorded by Delfeayo Marsalis and Patrick Smith

Recorded on January 12th & 13th, 1993 at the Grande Lodge of Masonic Hall. NYC

Mixed at Sony Music Studios, NYC

Original 24-bit recording using the Sony 3348 HR recorder and mixed on the Sony OXF-R3 digital console

Mastered utilizing DSD™.(Direct Stream Digital) and SBMIM Direct

“Tom Cat Blues recorded at:

Edison National Historic Site

National Park Service

U.S. Department of the Interior

West Orange, NJ

Jerry Fabris, Curator of Sound Recordings, Edison National Historic Site

Peter N. Dilg, Acoustic Recording Engineer . •

The Management Ark, Inc.

Santa Fé. MM – Princeton, NJ

Edward C. Arrendell II • Vernon H. Hammond III

Wessell “Warmdaddy” Anderson is a Leaning House artist.

Danilo Perez appears courtesy of The Verve Music Group.

Eric Reed appears courtesy of The Verve Music Group.

Art Direction and Design: Kiku

Photography: Lee Crurn; back cover: CORBIS

Signage: David Ellis

Series Logo: Drue Kataoka

Personnel

- Eric Lewis – piano

- Eric Reed – piano

- Danilo Perez – piano

- Reginald Veal – bass

- Victor Goines – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet, bass clarinet

- Wess “Warmdaddy” Anderson – alto sax, sopranino sax

- Wycliffe Gordon – trombone, tuba, trumpet

- Lucien Barbarin – trombone

- Ron Westray – trombone

- Dr. Michael White – clarinet

- Harry Connick, Jr. – piano, vocals

- Herlin Riley – drums, tambourine

- Don Vappie – banjo, guitar

Also of Interest

-

Photo Galleries

Photo Galleries

The Music of Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver Dizzy’s Jazz Club (day #5)

-

Photo Galleries

The Music of Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver Dizzy’s Jazz Club (day #4)

-

Photo Galleries

Photo Galleries

The Music of Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver Dizzy’s Jazz Club (day #3)

-

Photo Galleries

Photo Galleries

The Music of Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver Dizzy’s Jazz Club (day #2)

-

Photo Galleries

The Music of Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver Dizzy’s Jazz Club (day #1)

-

Photo Galleries

The Wynton Marsalis Ensemble performing at Jazz in Marciac 2011

-

Photo Galleries

The Wynton Marsalis Ensemble in soundcheck at Jazz in Marciac 2011

-

Photo Galleries

Photo Galleries

Wynton Marsalis rehearsing the music of King Oliver and Jelly Roll Morton at “Jazz in Marciac” 2011