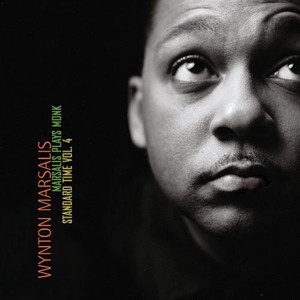

Marsalis Plays Monk - Standard Time, Vol. 4

Just as Thelonious Monk remains the most modern of jazz composers some twenty years after his death, so Wynton found inspiration for playing his music in the groundbreaking, and still avant-garde, music that Louis Armstrong created with his 1927 and 1928 jazz orchestras. Both Armstrong and Monk were artists of great surprise. On the evidence here – provocative interpretations of “Evidence,” “Let’s Cool One,” “Brilliant Corners,” and other Monk masterpieces – there’s no doubt that Wynton is, too.

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Septet |

|---|---|

| Release Date | April 21st, 1999 |

| Recording Date | September 17-18, 1993; October 3-4, 1994 |

| Record Label | Columbia / Sony Classical |

| Catalogue Number | CK 67503 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Thelonious | 4:51 | Play |

| Evidence | 4:25 | Play |

| We See | 3:20 | Play |

| Monk’s Mood | 3:02 | Play |

| Worry Later | 6:15 | Play |

| Four In One | 5:49 | Play |

| Reflections | 6:15 | Play |

| In Walked Monk | 4:22 | Play |

| Hackensack | 3:03 | Play |

| Let’s Cool One | 4:10 | Play |

| Brilliant Corners | 4:49 | Play |

| Brake’s Sake | 6:59 | Play |

| Ugly Beauty | 2:38 | Play |

| Green Chimneys | 4:42 | Play |

Liner Notes

“In Walked Monk”

This recording is one of the most original overall renditions of the music of Thelonious Monk. It is on par with the wonder of the subject. Wynton Marsalis’ arrangements and those of his musicians almost always frame the work in completely fresh ways while maintaining Monk’s power. There is plenty of surprise and plenty of swing. This should be expected of Marsalis, who is always coming from a place other than whatever convention dominates the moment. Only he could have conceived this way of approaching the work of the master. You got to watch that man. He’ll upset you. Marsalis says that in a number of the arrangements he was trying to reinvent for this period the kinds of things Louis Armstrong played with jazz orchestras in 1927 and 1928, such as Chicago Breakdown, Symphonic Raps, and Savoyager’s Stomp.

“I always loved that music,” says Marsalis. “It was original, well thought out, and you didn’t know what was going to happen. It had those textural changes. Thick ensembles, then a duet, or just a few people playing. Breaks. Surprises. Long solos. Very short ones. Strange tags on the ends of tunes. You can hear that from the first track on this album. I thought some of this Monk music would be perfect for those kinds of arrangements. This is not an attempt to make fun of that style or of Monk. Oh, no. What I wanted to do was take the conception of how to manipulate sound from that period and put it together with Monk. That’s why you’ll hear Herlin Riley playing the melody or accompanying a piano solo by himself. Wes and I will play a duet over the rhythm section. You’ll hear collective improvisation. High reeds and brass. Counterpoint. Somebody will play obbligatos to the arrangements. We’ll make Worry Later sound like a party that somebody just opened up the door on. Or Herlin and I will put a duet tag on Green Chimneys. I wanted to go deep into the tradition of the music but adapt what I found to fit with Monk, who is as deep as you can get.”

To mention some examples of other high points, there are remarkable moments such as the arrangements of Thelonious, Evidence, Worry Later, Four In One, Reflections, and Why Don’t You Face the Facts?, which is usually known as Monk’s Mood. Those who know the master’s music will notice just how superbly his voicings are addressed and well his language is understood, as with the stout chorus Marsalis wrote for Four In One. There is more, of course. There are the differently sized ensembles and the disruption of conventional improvising formats that neither duck nor impede swing but seek another way to get at it. There is the shocking opening of We See, a virtuosic jolt of musical caffeine for your ear. There is the breathtaking work of Herlin Riley, which surely proves him one of the finest drummers to have emerged over the last decade, possessed of an exceptional touch, sparkling imagination, and a thick repository of grooves. There is the trumpet feature on Four In One, which might remind many of the way John Coltrane used to shock saxophonists with his expansions of what we expected of the individual player’s technical command. It is surely one of the most shockingly authoritative creations we have heard from that instrument in this or any other era.

Why, however, was this recording made? Or, better, what is it that attracts Marsalis to Monk since one of the best developments of jazz repertoire, is that so many other musicians have–finally–gone on to record more than the three Monk songs Miles Davis popularized, ‘Round Midnight, Well, You Needn’t, and Straight, No Chaser? Marsalis is very clear.

Monk’s music is completely integrated. The harmonic progressions, the melody, and the rhythm are all woven into a seamless fabric of swing. And soul. His compositions demonstrate absolute authority and a belief in the fundamental proposition of jazz music, which is elegant execution, syncopated melodies on top of, through, around, and upside the head of the form. The most penetrating fact about Monk’s music is that it is difficult–and fun–to play. His themes are timeless and he teaches us how to be modern without stooping to the kinds of cacophonous clichés that have been misinterpreted as bold or futuristic.

Monk uses wide intervals, jagged melodies, unexpected rhythms. But, instead of making us feel like we have stepped into the calamitous caterwauling at the end of the world, Monk brings us right down home for a meal of some blues and swing, two ingredients that cannot be avoided if one wishes to continually summon others to one’s table. His music is virtuosic but now showy. It is tender, harsh, playful, deadly serious. Whenever we are on the road and I introduce a song by Thelonious Monk, someone in the audience–no matter whether we are in Timbuktu, Kalamazoo, or Lima, Peru–someone always shouts “Yeah.” That one word, yeah, acknowledges the incorruptible integrity of Monk and his great music. As Coltrane said, you can learn from Monk in every way. Coltrane was right. Monk can teach you melody, simple melody or complex melody, simple harmony or complex harmony, simple rhythm or complex rhythm. When it’s simple or complex, you can be sure it’s always profound. You can tell Monk hated the meaningless. To him, music was something you had to revere but that reverence didn’t stop you from being funny, though. His integrity and expression were total. In fact, I always noticed when I would talk to Miles or Dizzy or Elvin Jones, when Monk’s name would come up, they would begin to stammer. That means something. They knew who he was.

Hmmm.

Who, exactly, was this man who had been born in 1917 in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, had grown up in New York, and had died in 1982 in New Jersey? Was he only a person who remade the stride piano style into an unpredictable adventure and helped create the fundamental elements of the bebop movement that brought Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie out of obscurity? Was he only a brilliant composer? Did he do more than substantially influence Dizzy Gillespie, John Lewis, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Wayne Shorter, either through his harmony or his rhythms or his melodies or his motific manner of improvising?

Above all else, Thelonious Monk was a nobleman, a self-made aristocrat whose soul was comprised of down-home cross ties and steel Manhattan rails. That spirit could carry the glory-bound train. This quality of celestial selfhood allowed Monk to live up to all of the demands of a most difficult art. Writ large by virtue of his genius, the artistry of this man was sensual and high-minded. It rendered human values with gutbucket specifics and contemplative abstractions. He so mastered the sound of what this writer calls “industrial lyricism” that his song book of compositions is a set of propositions intent on achieving the poetic within the context of skyscrapers, mass technology, and overcrowding. Monk’s musical responses and reinterpretations of what could be a dehumanizing and overwhelming manmade environment are quite clear. His compositions are constructed with sophistication, grit, and mother wit. Their contents are comedic, romantic, tragic, mysterious, forthcoming, secretive, bold, and shy. In essence, that industrial lyricism always couples itself with industrial swing and makes the meaning of the metropolis and occasion for dance, either of the body or the spirit or both. Pat that foot and you get the point.

So Monk, like Ellington and Gershwin, is a poet of New York. His music speaks of the bridges, the sidewalks, the people, the buildings, the speed, the power, the overcrowding, the car horns, the parks, the enchantment of late night love talk on steps, fire escapes and roof tops, the weight and pace of tug boats, the gloom of empty night when all the skyscrapers and apartment buildings look like tombs, the noise of the school yard, the athletic joy of focused exercise and competitive games, and everything else that makes New York what it is. As Monk said, “Jazz is New York. You can feel it in the air.”

He knew well what he was saying because the grand master understood how thoroughly Manhattan remade whatever came into it, functioning like an aesthetic boot camp that prepared the talented to do battle with the formal, technical, and emotional obstacles to saying what one had to say with the most grace and style.

Every aspect of his work is superb. Monk had a superior sense of melodic line, an impeccable harmonic authority, an unsurpassed command of rhythm, the ability to swing a hole through an iron wall, and such control of timbre that his every touch seemed to reinvent the nature of the piano. His sound was enormous, a dark thunder, a fat ping, a gleeful shriek, a serenading choir of metal, felt, and wood. He could quiet a house with the power of his tone parting the air. Every aspect of his work was revolutionary in that it reaffirmed the absolute originality of the jazz idiom. As with all giants, when Monk was playing, he so dominated the moment that it seemed as though there was no other way to do it. The purity of the music was being revealed in all its strength and nuance through one person. He then took on the identity of light.

This is why Monk was something to see, a compendium of the essences of his idiom. There was the quality of the showman to his performances but that showmanship kept one foot in the world of the mysterious and undercut service to anything other than the moment, which, in jazz, is everything. When Monk was up there on the bandstand in one of his hats doing his jerky, stumbling turns and steps, his cheeks sucked in, his fingers snapping, he immediately put one in the world of the eccentric dancer from an older time of Negro show business, the guy whose control was masked by what appeared to be uncoordinated bumbling but was exactly the opposite. At the piano, stamping and sliding his foot, fingering the keyboard in a flat-digited manner, sweating like a pig, using all kinds of homemade techniques in order to turn the piano into a tuned set of drums and back into a piano or some piece of starling machinery that smacked or popped out dissonant chords in angular rhythms, Monk was as enthralling as he was dramatic and swinging.

That exotic aura gave him a particular identity, one so substantial that the marketing title of the “the high priest of modern jazz” actually worked. Any high priest transcends the conventional lines of though about time. Monk’s material was not linear because it, alike all truly great art, turned time into a triangle of the past, the present, and the future. When Monk wrote or played, the history of music was there, the time he lived in was captured in high relief, and the future was in place because it is through the poetic snaring of the truth that humanity speaks across the ages. That point at which language rises to the condition of invincible song is the moment at which all previous poetry, all present poetry, and all future poetry create that triangle, that pyramid of timeless time–no matter the idiom from which it arrives.

The poetic appreciation at the center of this paean is the sort of man of Thelonious Monk’s musical gifts deserves because his example is so pure. He stood out in his own time and he does in ours. It is always a wonder to listen to the music of a man who submitted to nothing other than his own inspiration and the desire to communicate with his audience on a level untainted by contrivance. What we hear from Wynton Marsalis and his musicians is so respectful of that quality that freshness upon freshness arrives. The musicians improvise as Monk himself did, using the themes and integrating them into the chords rather than ignoring the melodies in favor of the harmonies. They don’t imitate him because a thorough grasp of the conception is enough, which John Coltrane proved with his improvisation on Crescent, which is purely Monkian in its thematic coherence while being completely Coltrane. The remarkable playing by Marsalis, Eric Reed, and Wes Anderson on Brake’s Sake is a perfect example. Or there is the house-rocking use of the melody and its rhythms during Victor Goines’s feature on Green Chimneys. Don’t even talk about the duet Marsalis and Anderson play on Hackensack.

What is one to say of how Wycliffe Gordon always reminds us of how profoundly jazz musicians remade the trombone for purposes both gutbucket and elevated? The flow of the time and the breadth of the beats heard in both Reginald Veal and Ben Wolfe put them on the top line with the finest younger bassists. How about the masterpiece that is Marsalis’ own In Walked Monk? What a melody, what an arrangement, and what unsentimental but deep feeling for the man who inspired it. But this very recording is the sort of thing we ought to expect from Thelonious Monk, that he should move musicians to write and play as they do on this document. There is no stammering but every note and every beat you hear arrives in recognition of a superior being. The ongoing swing and the striking programming might even remind one of the feeling Monk himself created with his Criss Cross album for which Nica De Koenigswarter wrote of the master, “His greatness lies in the very fact that he transcends all formulae, all well-worn adjectives and clichés; only a new vocabulary, perhaps, could suffice. One thing, though, is certain: this is the happiest of albums, leaving one with an extraordinary feeling of elation.”

She could have been describing this album, given its avoidance of clichés and the new vocabulary that arrives through the masterful arrangements. In fact, she probably is saying something like that right now, edging in among Monk, Armstrong, and Ellington, all three of whom are listening closely, then pointing out what’s going on and, one by one, joking that, “Well, if it wasn’t for me!” One of them or all of them will probably say of Wynton Marsalis, “Those people down there better watch that young man. He’ll upset them.” As usual, they will be right. They made and know the music. He is following them in his own personality with increasing speed and authority. That is the way it always happens. If it wasn’t for the blues. If it wasn’t for the swing. It wouldn’t mean a thing.

- Stanley Crouch

Credits

All compositions written by Thelonious Monk (all published by Thelonious Music Corp./BMI except “Monk’s Mood” by Embassy Music Corp./BMI) except “In Walked Monk” by Wynton Marsalis (Skayne’s Music/ASCAP)

“Thelonious” and “Worry Later” recorded on September 17-18, 1993

All other songs recorded on October 3-4, 1994

Produced by Steve Epstein

Recording Engineer: M.G. Wilder

Mixing Engineer: Todd Whitelock

Assistant Engineer: James Biggs

Technical Supervisor: John Harris

Recorded digitally onto the Sony PCM 3324 DTR at the Grand Lodge of Masonic Hall, NYC

Digitally mixed on the Weiss/Ibis console at Sony Music Studios, NYC

The Management Ark

Edward C. Arrendell II – Vernon M. Hammond III

Art Direction Et Design: Kiku

Photography: Lee Crum

Logo Design: Drue Kataoka

Wessell “Warmdaddy” Anderson is a Leaning House artist.

Victor Goines appears courtesy of Rosemary Joseph Records.

Eric Reed appears courtesy of the Verve Music Group

www.columbiajazz.com

www.columbiarecords.com

www.sonyclassical.com

Personnel

- Reginald Veal – bass

- Wess “Warmdaddy” Anderson – alto sax, sopranino sax

- Walter Blanding – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet

- Victor Goines – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet, bass clarinet

- Ben Wolfe – bass

- Wycliffe Gordon – trombone

- Eric Reed – piano

- Herlin Riley – drums, tambourine

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Brake’s Sake - Wynton Marsalis Septet at Dizzy’s Club 2013

-

Videos

Videos

Reflections (rehearsal) - Wynton Marsalis Septet at Jazz in Marciac 2008

-

Videos

Videos

Four in One - Wynton Marsalis Septet in Warsaw (1994)

-

Videos

Videos

Reflections - Wynton Marsalis Septet in Warsaw (1994)

-

Videos

Videos

The Wynton Marsalis Septet in Maastricht (1994)

-

Videos

Videos

Green Chimneys - Wynton Marsalis Septet at Jazz in Marciac 1993

-

Videos

Videos

Blue Monk - Wynton Marsalis Quintet in New Zealand

-

News

News

The 10 Best Wynton Marsalis Albums