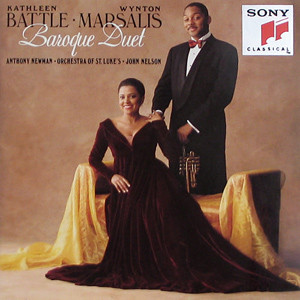

Baroque Duet

The performances on this recording recreate performances by some of the most famous singers and trumpeters of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and exemplify the various ways the trumpet was used in Baroque art music. The pieces range from military, religious, and regal in nature to mournful and sweet. Kathleen Battle and Wynton Marsalis display immense virtuosity and mastery of the various settings for voice and trumpet.

Clip from Baroque Duet VHS:

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis with Kathleen Battle and Orchestra of St. Luke’s |

|---|---|

| Release Date | April 21st, 1992 |

| Recording Date | September 28 & October 8, 1990 & July 22, 1991 |

| Record Label | Sony Classical |

| Catalogue Number | SK 46672 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download, VHS |

| Genre | Classical Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Georg Friedrich Händel (1685-1759) | ||

| Let The Bright Seraphim – (From Samson, HWV 57) | Play | |

| Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725) – (from 7 Arie Con Tromba Sola) | ||

| No. 1: Si suoni la tromba | Play | |

| No. 2: Con voce festiva | Play | |

| No. 4: Rompe sprezza | Play | |

| No. 6: Mio Tesoro per te moro – (Aria In Forma Di Menuet Alla Francese) | Play | |

| Alessandro Scarlatti Su le sponde del Tebro – (Cantata a voce sola con Violini e Tromba) |

||

| I. Sinfonia. Grave | Play | |

| II. Recitativo | Play | |

| III: Sinfonia – Aria | Play | |

| IV. Recitativo | Play | |

| V. Aria. Largo | Play | |

| VI. Aria. Poco mosso, sempre dolce e leggiero – Ritornello | Play | |

| VII. Recitativo | Play | |

| VIII. Aria – Sinfonia. Grave (da capo) | Play | |

| Georg Friedrich Händel – (from Ode for the Birthday of Queen Anne) | ||

| Eternal source of light divine | Play | |

| Luca Antonio Predieri (1688-1767) | ||

| Pace una volta (from Zenobia) | Play | |

| Alessandro Stradella (1644-1682) Sinfonia before Il barcheggio – [Part I] for Trumpet, Strings and Basso Continuo (D Major) |

||

| I. Spiritosa, e staccata | Play | |

| II. [Allegretto-Corrente] | Play | |

| III. Canzone | Play | |

| IV. [Allegro] | Play | |

| Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 – 1750) – (from Ich hatte viel Bekummernis, Cantata No. 21) | ||

| Seufzer, Tranen, Kummer, Not | Play | |

| Georg Friedrich Händel: – (from: Oh come chiare e belle, HWV 143, Cantata No. 19) | ||

| Alle voci del bronzo guerriero | Play | |

| Johann Sebastian Bach: – (from Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen, Cantata No. 51) | ||

| I. Aria: Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen | Play | |

| IV. Chorale: Sei Lob und Preis mit Ehren; Alleluja | Play | |

Liner Notes

From earlier times, the trumpet has represented military, religious and regal pomp, and until about 1600 trumpets were generally relegated to outdoor, ceremonial occasions of these types. After this time they began to be welcomed “indoors” into the chamber, but even so their association with military, regal and religious occasions remained, as is evident in such famous trumpet pieces as Handel’s “The trumpet’s loud clangor excites us to arms,” Ode for St. Cecilia’s Day (1739); Purcell’s “Sound The Trumpet,” Welcoming Ode for James II (1687); and Handel’s “The trumpet shall sound” (“and the dead shall be raised, Messiah (1742). The real and symbolic of the trumpet makes its combination with quieter instruments and voice seem at first improbable, but a softer, sweeter style of playing in high (“clarino”) register was typical in art music for the trumpet, so that seventeenth-and eighteenth-century composers not only combined with voice and trumpet, but regularly paired the trumpet and recorder, as in Bach’s second Brandenburg Concerto.

The voice was deemed an especially good match for trumpet. In particular, the sound of the castrated male voice (castrato) was often compared to the brilliance and strength of the trumpet and all that it symbolized. Throughout the Baroque era, heroic male operatic roles, such as Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great, were typically sung by castrati. If we find the association of the castrato and a high (soprano or alto) singing range with male virility surprising today, it is partly because we fail to make a connection with the sound of the trumpet. Eighteenth-century English music historian Charles Burney (1726-1814) describes for us one remarkable competition that sprang up in 1721or 1722 between a trumpeter and perhaps the most famous castrato, Carlo Broschi (Farinelli):

[Farinelli] was seventeen when he left [Naples] to go to Rome, where during the run of an opera, there was a struggle every night between him and a famous player on the trumpet in a song accompanied by that instrument; this, at first, seemed amicable and merely sportive, till the audience began to interest themselves in the contest, and to take different sides: after severally swelling a notes, in which each manifested the power of his lungs, and tried to rival the other in brilliancy and force, they had both a well and shake together, by thirds, which was continued so long, while the audience eagerly waited the event, that both seemed to be exhausted; and, in fact, the trumpeter, wholly spent gave it up, thinking, however, his antagonist as much tired as himself, and that it would be a drawn battle; when Farinelli, with a smile on his countenance, shewing he had only been sporting with him all that time, broke out all at once in the same breath, with fresh vigour, and not only swelled and shook the note, but ran the most rapid divisions, and was at last silenced only by the acclamations of the audience.

The sound of the trumpeter in Baroque chamber music can be gauged partly by its pairings with recorder and voice, and partly again by contemporary evidence on the similarity between it and the oboe. In The Sprightly Companion, a collection of marches published in London (1695), it is remarked that the oboe is “not much Inferiour to the Trumpet; and for that reason the greatest of Heroes of the Age… are infinitely pleased with This for its brave and sprightly tone.” In Handel’s one opera for Florence, Rodrigo (1707), a solo oboe accompanies the aria that begins, “Stragi, morti, sangue ed armi, con bellici carmi gia grida la trombe” (Slaughter, death, blood and arms, with warlike songs now cries the trumpet”). Presumably no trumpeter was available (for when Handel borrowed this aria in the London production of Radamisto, he used the trumpet), but the approximation must have been close. Indeed, in 1728 a French visitor to London (Pierre Jacques-Fougeroux) describes Handel’s orchestra as containing trumpets (which it didn’t at that time) and no oboes (which it certainly did). It has been surmised that Fougeroux “mistook Handel’s vigorous oboes for trumpets.”

The performances on this recording by Kathleen Battle and Wynton Marsalis of music for voice and trumpet recreate performances by some of the most famous singers and trumpeters of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and exemplify the various ways the trumpet was used in Baroque art music. For example, the three selections by George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) specifically represent the trumpet’s three symbolic uses: military, regal, and religious. “Alle voci del bronzo guerriero” is the final aria of a cantata for three voices and instruments, O come chiare (HWV 143: “Oh! How bright”) written by Handel in 1708 to celebrate the military help his patron the Marquis Ruspoli gave Pope Clemens XI in the Spanish War of Succession. The characters are allegorical: Olinto pastore (soprano) is a shepherd representing Ruspoli himself; Tebro fiume (alto castrato), the Tiber River; and Gloria (soprano), glory. The text of the final aria, sung by Olinto, begins, “To the brave warrior’s voices, let us reply with festive echo,” and for the first time in the cantata the trumpet enters (and continues playing in the concluding celebratory trio). Margherita Durastanti, Ruspoli’s primary singer and prima donna who premiered the title roles Agrippina (1709) and Radamisto (1720, a male “pants” role), sang the leading part of Olinto.

In 1714, Handel opened Ode for the Birthday of Queen Anne with a solo movement for voice and trumpet heralding the queen’s role in the Peace of Utrech (1713), which had finally brought an end to length Spanish War of Succession. Handel apparently couldn’t have cared less about politics. For Ruspoli, in O come chiare he had honored the victories of one side of this conflict, for Queen Anne he honored the other side. The text of Ode for the Birthday of Queen Anne by poet and dramatist Ambrose Philips compares Queen Anne to the sun. Similarly, the trumpet and voice compete with and echo each other “with double warmth.” According to his manuscript score, Handel wrote the vocal part of this movement for Mr. Richard Elford, countertenor, who was described by a contemporary musician as renowned for giving “such a due Energy and proper Emphasis to the Words of his Musick.”

Like “Alle voci del bronzo guerriero,” “Let the bright Seraphim” from Samson (1743) provides a climactic final aria. Handel only added this aria (among others) to his completed score of 1741 sometime before the first performance, where it was sung by Madame Christina Avoglio, who had premiered the principal soprano part in Messiah (1742) and apparently performed Cleopatra in the Hamburg performance of Handel’s Giulio Cesare (1729). Not only Avoglio’s roles, but also contemporary accounts lead one to speculate a striking similarity between the voices of Madame Avoglio and Kathleen Battle. Handel himself wrote that “Sigra Avolio [sic]… pleases extraordinary.” The obbligato trumpet part was written for the English trumpeter Valentine Snow, widely regarded as “the finest trumpeter of the day.” It is for Snow that Handel wrote the solo trumpet parts in Messiah (including “The trumpet shall sound”) and other works. “Let the bright Seraphim” (“…their loud, uplifted angel trumpets blow”) celebrates the triumphs of Samson in death and of life everlasting.

Of course, not all trumpet music fell directly into the military, regal or religious categories. The Sinfonia of Alessandro Stradella (1644-1682) before his serenata Il barcheggio (1681) takes the form of a typical chamber sonata with a succession of four dance movements ([Allemande]; Corrente; Canzone; [Gigue]) in which the solo trumpet is contrasted with a string orchestra. Throughout the Sinfonia, the trumpet part has no symbolic value. It is perhaps relevant, however, that Il barcheggio is a wedding serenata, so that the solo trumpet, as opposed to, say, a solo violin, may have signaled the celebratory nature of the work. According to the score of Il barcheggio preserved in Modena, this overture by Stradella was “the last of his Sinfonias.” The composer, who during his short life was involved in an embezzlement scheme against the Catholic Church and in 1677 avoided assassination as a result of an affair, was murdered in 1682 as a result of another affair.

Zenobia by Luca Antonio Predieri (1688-1767) was first performed in Vienna, 28 August 1739 in honor of the birthday of the empress. The libretto by Pietro Metastasio, the most famous and prolific author of operaseria librettos, tells the same story as Handel’s Radamisto, celebrating the conjugal love of Radamisto and his wife Zenobia. In the scene preceding the aria “Pace una volta,” Zenobia has refused the protection of the Prince Tiridate despite the danger she will be in if left alone. Because of his previous attempts to force his love on her, she says, “It is a greater risk to stay with you…I ask you in pity’s sake to leave me in peace.” In her aria she repeats this sentiment, “Let me find peace and calm at least once.” She goes on to say, “Awaken not the war and tempest within my breast,” but the trumpet is never used to depict military or violent imagery. Rather it alternates between sustained notes and agitated two-note “sigh” patterns. Both this aria by Predieri and the Sinfonia by Stradella exploit the chamber music qualities of the trumpet so newly and richly explored in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Among the pieces by Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725) are four arias from a set of seven for voice, trumpet solo and continuo (harpsichord and cello playing the same bass line with the harpsichord improvising harmonies). The first of these, “Si suoni la tromba” (“Let the trumpet sound”) makes use of the trumpet’s military imagery, and both the voice and trumpet must navigate difficult divisions and trilling on long sustained notes, much in the manner of the contest in Rome between Farinelli and the trumpeter described by Burney. “Con voce festiva” (aria 3) celebrates the Tiber River, but still mentions the trumpet in the text, which calls for it to “respond with an echo…to the playful waves.” The flowing 12/8 meter affords continual opportunity for voice and trumpet to alternate and overlap in waves of sound. “Rompe sprezza” (aria 4) tells of a young woman who callously breaks hearts. Calling for a somewhat detached and staccato style, and with the text broken sometimes into single words, the voice is mimicked by the trumpet. “Mio tesoro” (aria 6: “Aria in the form of a French minuet”) is a lament in which a woman calls out to her absent beloved. The trumpet plays the melody before and after the singer, transforming her song into a plaintive, wordless cry.

Scarlatti’s multi-movement cantata Su le sponde del Tebro is scored for soprano, solo trumpet, strings and continuo. It too is a lament; the shepherd Aminta on the banks of the Tiber bewails the faithlessness of his beloved Chloris. The singer actually takes two roles, narrating the story in the recitatives and speaking with Aminta’s voice in the arias. The opening Sinfonia for trumpet, strings and continuo is similar to the first movement of the Stradella Sinfonia. After the first recitative setting the scene, there is a second short Sinfonia leading into the first aria, “Contentatevi” (“Be content”) with trumpet obbligato. Here the trumpet doesn’t simply alternate with or echo the voice, but intertwines complimentary and contrasting motives. After a second recitative, two movements express Aminta’s great grief, during which the trumpet is silent. These are followed by a short instrumental movement. Finally, after a recitative in which Aminta is seen to resign himself to his fate, the final expresses this directly, “Tralascia pur di piangere” (“Cease to weep”). In this aria the trumpet returns to the orchestra, but is limited mostly to interludes between vocal entries. The voice, like Aminta, is left alone supported only by continuo.

In Su le sponde del Tebro, as in “Rompe sprezza” and “Mio tesoro per te moro” of the 7 Arie con tromba sola, there is no mention of trumpet in the text, nor any imagery usually associated with the trumpet. In these pieces the trumpet is used for its sweet, almost plaintive sound. In his cantata Ich hatte viel Bekummernis (BWV 21, composed before 1714), Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) calls for a solo oboe to accompany the aria “Seufzer, Tranen, Kummer, Not,” a religious lament similar to Scarlatti’s love songs: “Sighs, tears, grief, misery, anxious longing, fear and death, rend my troubled heart.” In this recording the trumpet replaces the plaintive oboe, reversing the situation in Handel’s “Stragi, morti, sangue ed armi,” where the oboe at first substituted the brilliant trumpet.

Bach’s Jauchzet Gott (BWV 51, composed about 1730) is perhaps the best known work written for voice, trumpet and string orchestra. The works calls for extraordinary virtuosity from both the singer and trumpeter; the singer’s part not only demands agility and speed, but the range extends up to the high c’’’. Although Bach normally wrote his soprano solos and parts for choirboys, he may have written this virtuoso cantata to demonstrate his skill to the operatic city of Dresden, where he often visited with his son Wilhelm Friedemann. One hypothesis suggests the vocal part was written for the soprano castrato Giovanni Bindi, whose operatic roles also extended to high c’’’. A more recent suggestion is that Bach intended it for the soprano Faustina Bordoni, who had been Handel’s prima donna in London in the second half of the 1720s and now was married to the composer Johann Adolf Hasse. According to this theory, Bach only learned after the fact that his coloratura showpiece exceeded Faustina’s range by at least a third and could not be performed. Regardless of the specific identity of the singer (if there was one), we can be relatively sure that Jauchzet Gott is the only music Bach wrote for soprano that was not intended for a choirboy to sing.

Ellen T. Harris

Credits

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

1. Let The Bright Seraphim (From Samson, HWV 57)

Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725)

(From 7 Arie Con Tromba Sola)

2. No. 1: Si Suoni La Tromba

3. No. 3: Con Voce Festiva

4. No. 4: Rompe Sprezza

5. No. 6: Mio Tesoro Per Te Moro

(Aria In Forma Di Menuet Alla Francese)

Marc Goldberg, bassoon continuo

Alessandro Scarlatti:

Su Le Sponde Del Tebro

(Cantata A Voce Sola Con Violini E Tromba)

6. I. Sinfonia. Grave

7. II. Recitativo

8. III. Sinfonia — Aria

9. IV. Recitativo

10. V. Aria. Largo

11. VI. Aria. Poco Mosso, Sempre Dolce E Leggiero — Ritornello

12. VII. Recitativo

13. VIII. Aria — Sinfonia. Grave (Da Capo)

George Frideric Handel:

14. Eternal Source Of Light Divine

(From Ode For The Birthday Of Queen Anne, HWV 74)

Luca Antonio Predieri

15. Pace Una Volta (From Zenobia)

Libretto By – Pietro Metastasio

Alessandro Stradella (1644-1682)

Sinfonia Before Il Barcheggio

[Part I] For Trumpet, Strings And Basso Continuo

(D Major)

16. I. Spiritosa, E Staccata

17. II. [Allegretto — Corrente]

18. III. Canzone 1:44

19. IV. [Allegro]

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

20. Seufzer, Tränen, Kummer, Not

(From Ich Hatte Viel Bekümmernis, Cantata No. 21)

George Frideric Handel

21. Alle Voci Del Bronzo Guerriero

(From O! Come Chiare E Belle, HWV 143, Cantata No. 19)

Johann Sebastian Bach

(From Jauchzet Gott In Allen Landen, Cantata No. 51)

22. I. Aria: Jauchzet Gott In Allen Landen

23. IV. Chorale: Sei Lob Und Preis Mit Ehren; Alleluja

Krista Nennion Fennen, violin

Erico Sato, Violin

Orchestra of St. Luke’s – John Nelson, conductor

Anthony Newman, harpsichord and organ continuo (all selections)

Daire Fitzgerald, cello continuo (all selections)

John Feeney, bass continuo (all selections, except track 11)

John T. Kulowitsch, bass continuo (track 11)

Recorded at the Academy of Arts and Letters, New York City. September 28 & October 8, 1990 & July 22, 1991.

This recording was mastered using 20-bit technology for “high definition sound”

Producers: Steven Epstein, Thomas Frost

Balance engineer: Charles Harbutt

Editing: Ellen Fitton

Remote technical Supervisor: Ed Visnoske

Cover design: Josephine DiDonato

Cover photos: Ken Nahum

Couture for Miss Battle: Rouben Ter-Arutunian

Personnel

- Kathleen Battle – vocals

- Anthony Newman – conductor

- John Nelson – conductor