Wynton’s Top Ten: Compelling Works on the Subject of Freedom

Introducing a new Jazz at Lincoln Center series titled “Wynton’s Top Ten,” a monthly listicle curated by Wynton Marsalis. This month, Wynton shares his “Top Ten” picks for “Compelling Works on the Subject of Freedom” and his annotations behind each selection.

1. The Constitution of the United States (Senate.gov)

Without the idealism of our country’s founding documents, we’re having a different discussion. An empire doesn’t negotiate with those it has defeated, exploited, and enslaved—but a republic might. This document keeps us focused on pursuing larger mutual objectives.

At the beginning of every year, I ask my Juilliard students, “What is the US Constitution designed to do?” After some extended discussion, we get from a few – blank looks and a partial listing of rights to an understanding of it as a blueprint for leveling various playing fields, IF WE ARE UP TO FIGHTING TO REACH FOR AND MAINTAIN THAT BALANCE. Like the elusive, elegant, and elastic art of swinging, this document tells us that our freedom is a never-ending negotiation that requires and commands your absolute attention, energy, and interest.

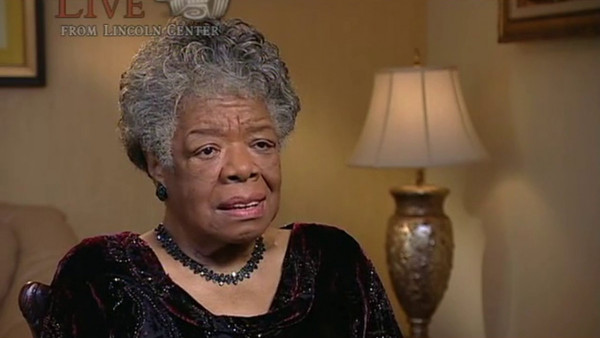

2. “Still I Rise” – Maya Angelou (Poetryfoundation.org)

I grew up loving Maya Angelou because my mother loved repeating the title of her masterpiece memoir, “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.” In 2003, I was honored to do an audio book with Dr. Angelou, “Music, Deep Rivers in My Soul,” that included etchings by the excellent figurative artist Dean Mitchell. She managed to get the whole history of Afro-American music in one short poem.

“Still I Rise” however, is one of my favorite works of art across all cultures and history.

She teases and tantalizes her oppressor with a devastating mixture of humor and taunting and vinegary wit. Let’s just say it’s “super-blues-metaphor” itself. Turning up to down and the classic pathologies of a beat-down, upside down, she sashays words like sassiness, sexiness and haughtiness, ha-ha. At the very end of my first symphony, ‘All Rise’, that premiered at the end of 1999, I wrote a New Orleans parade march with lyrics and music based on the feeling of this poem. Like everyone, I also loved just hearing her talk; the cadence and the round lyricism of her voice. It was down-home music and always made me miss Louisiana.

3. “The Gulag Archipelago” – Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (Wikipedia.org)

I read this in high school because my brother was reading it and I liked the name. I couldn’t interpret it accurately, because 1970’s propaganda about Russia made me perceive them in the distorted view of “others” or “enemies”.

On the other side of the coin, Solzhenitsyn is bone-chillingly critical of Stalin and the whole Communist system, but I also couldn’t perceive the depth of the human nuances in his teachings, because I thought that this book being taught (when we never read a word of Black nationalism or consciousness which was very popular at that time) as a form of “American propaganda”. Thoughts of propaganda got me both ways.

Later, in the early 80’s, after going to countries still under what was called “Iron Curtain”, I learned from young people in Poland and the (now) Czech Republic themselves. Their oppression was definitely not propaganda, and they considered jazz to be a principal agent of freedom.

4. “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave” – Frederick Douglass (Docsouth.unc.edu)

Frederick Douglass intelligently covers everything that systematically reinforced the “peculiar institution”.

From the pangs of first realizations as a child, to understanding that your objectives are opposite your master’s, to the cruel humor of naming a holiday whiskey ‘Liberty’ while giving slaves too much of it to drink and causing them to equate that word with being sick, to the irony of wanting to shine for the master, to the hypocrisy of the pious who praise the lord and starve and beat the slave, to the excitement of becoming free, to paying the personal price of politics when your evolving views become irreconcilable with trusted friends and mentors. It is cornerstone Americana and should be read by all of us.

5. “The Diary of Young Girl” – Anne Frank (Wikipedia.org)

Her book made you understand the possibility of retreating into the life of your mind to find freedom. We had to read this in school, and back then, in the early 70’s, I looked at it as some more indoctrination into a white point of view only because we never read anything meaningful by a black person from the past, let alone a kid!

But, as I remember passing from the myopic prejudices of our local way of life to the actual facts of her book, I was and remain struck by: 1) how intimate the writing was – because we boys didn’t understand anything about how adolescent girls thought about boys; 2) how she found freedom in the ability to express herself under life or death pressure taught you that freedom could be understood in the context of limitations; 3) how after all of what she went through- they got her. She died. Damn!! Made you understand that life is not a Hollywood movie but was actually only what it was—-no more, no less. It was heartbreaking at the age of 13.

6. “I Write What I Like” – Steve Biko (Google Books)

He was so intelligent. A charismatic speaker who understood the value of coalitions across impossible-to-cross-tribal lines. Mr. Biko had a big, big dream, but also could conceive the mechanics to achieve it. I loved everything about him. His ability to mobilize young people was inspirational and transformative. And he was so clear and soulful. They had to kill him.

He attacked from all angles and didn’t seek to build a prejudiced constituency. Like an informed modern jazz musician, he challenged the fake liberal narrative in which an unqualified “expert”, who actually knows far less than the worst of students, is put in the unearned role of critic and dispenser of wisdom. Mr. Biko said, “I am against the superior-inferior white-black stratification that makes the white a perpetual teacher and the black a perpetual pupil (and a poor one at that).”

I was 15 when he was murdered, and he was not well known at all. The small group of three teenagers I knew who followed international liberation figures, knew what had happened. They just got him. At that time, we connected it mythically, with Dr. King and with Robert Kennedy.

7. “Disasters of War” – Francisco Goya (Parkwestgallery.com)

I encountered these in my early 20’s in New York. Writer Stanley Crouch said, “Guess when these were done?” I said, “20th century.” He laughed and said, “Wrong! Early 19th! He was doing this in the early 1800s man. Goya was mean.”

These are 82 prints by an old master that are a powerful reminder of the inhumane consequences of war. Over 40 bear the description “I saw it” like Frederick Douglass’ book inscribed: ‘written by himself’.

In Goya’s hand, the brush is a scalpel. He gives us a front row seat to the corruption and abuse of power that destroys quality and conception of life. Though specifically dealing with Spain between 1810-1820, his belief in decency, simmering rage and bitingly accurate observations speak across time directly to us, as if they were done yesterday. I have a copy of one hanging in my bedroom.

8. “Letter from A Birmingham Jail” – Martin Luther King Jr. (University of Texas)

I was 18 years old playing with Art Blakey in Mikell’s, a legendary NYC club on 97th and Columbus, where James Baldwin’s brother, David, was the barkeeper and all kinds of great cultural figures came to hang and check out the music. Deep into one night, I was arguing with a white kid my age and in the course of our heated back and forth on “cultural” issues, he asked if I truly knew who King was. Being of my generation (we loved Malcolm) I condescended to Dr. King. He asked, “had I read this Letter?” I bluffed around it and he said, “Of course you haven’t because you’re Blaaaaack and y’all never know your own great stuff.” Well I cussed him out, and so on, but felt that we both actually knew the truth. That encounter and his boldness, made me understand that I couldn’t rely on my poor high school education in black studies as an excuse. I was sure he didn’t study it in school either, just as surely as I knew that both my parents knew about it. The next day I started studying my Dr. King.

9. “American Founders: How People of African Descent Established Freedom in the New World” – Christina Proenza-Coles (Americanfoundersbook.com)

Christina Proenza-Coles defines freedom through the context of responses to the limitations placed on it. And she lets you know that the Africans in America fighting for freedom defined the rights by being what they were told they could not be. She takes her time and is very detailed and proud with granular researched information, but gets to it as it goes along, as many really good things do. This book is perfect for this time and rewards the time spent with many nuggets.

10. “Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo”” – Zora Neale Hurston (Vulture.com)

I have always loved Zora Neale Hurston. She was ostracized by the in-crowd of the Harlem Renaissance because she was too soulful and shamanistic. This book just came out in 2018 (based on interviews from 1927) but it’s the type of book my mother and father would tell me to read, and I would not read it just to show that I could be proudly ignorant.

The passage from Africa to America, from freedom to slavery to partial freedom after the Civil War, is clearly detailed here. Zora Neale was a genius. There is so much complex human texture rendered so naturally. This book also details the tragedy of passing generations that aren’t up to the heroic challenges set before them by the weight of the achievements that preceded them and by the persistence of a deep and actively evolving oppression.

- Wynton