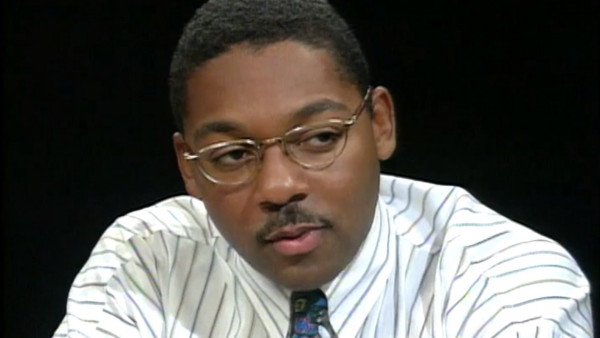

Crouch

(photo by: Frank Stewart)

Reading various articles, social posts, and obituaries that have appeared over the past 24-hours about Stanley Crouch’s passing, I’ve had to laugh out loud at some of them because, as the Bible says, “Death doesn’t get the last word” and neither does Stanley. I’ve noticed the sharp opinions of some writers whose work was backgrounded by his mastery, going about the important business of putting him in what they see as his proper place so that their own opinions and understandings can sit easier (in their minds) as more sensible or superior to his. Funny, because he always said, “When you’re dead you can’t defend yourself.” And he was right.

Stanley and I spoke almost every day for over 35 years. Although many of our conversations ended in argument, speaking with him was one of the most fascinating and richly rewarding experiences of my life. It was impossible to converse with him and not learn something—even if you only learned what you didn’t agree with. Stanley, on the other hand, could be incited to new thoughts and ruminations by a strongly argued position and would later acknowledge and even expound on his changed point of view.

He believed in rigorous study and in very direct engagement, preferably in person. It could, on very, very few occasions, end pugilistically. There it is, and there it was. Stanley once called me late at night and announced, “Man, I just wasted two hours listening to another long, boring piece you wrote. Why do you write those long-ass interminable pieces?” I asked him, “What long music do you like?” and went on to give a roll call of great extended compositions. He replied, “None. I don’t like ANY of it.” We both had to laugh at the absurdity of it all.

Stanley was not for the thin-skinned. Larger than life, he could be over the top in one moment and sweet as pie the next. His way of being right in front of you with a different and often unpopular opinion was absolutely countercultural and out of place in this cultivated era of eye winks, double and triple meanings, and fanciful and purposeful corruption of language and intention that further discredits our country’s media with each passing day.

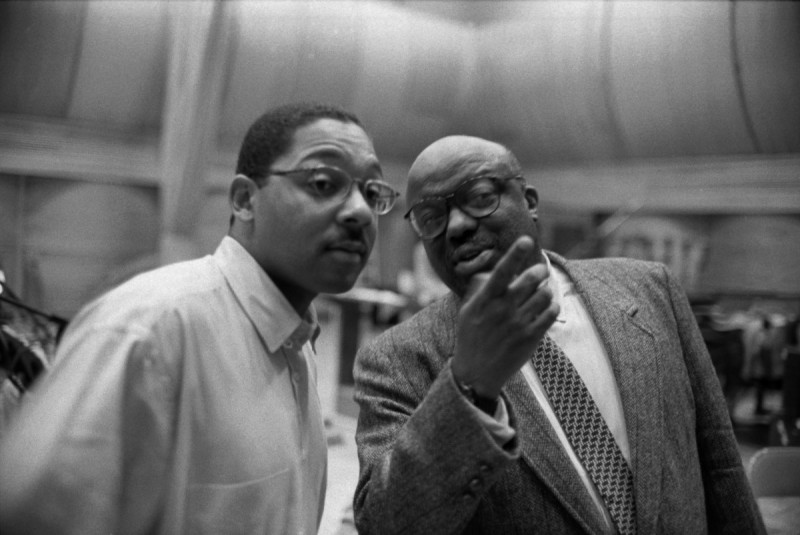

My relationship with Stanley was rooted in the dozens. I had just turned 18 when we met for the first time at the Upper West Side jazz club, Mikell’s. He started off saying to me, “You can’t be that boy from New Orleans they sayin’ can play. You sound sad, but that thin raggedy jacket is telling me you don’t know anything about this New York winter, so… you might be him.” I had no idea of who or what he was. I came back to him with, “Man, you got the nerve to talk bad about somebody while you standin’ up here looking like a raccoon with them rings around your eyes.” We immediately started laughing and hit it off.

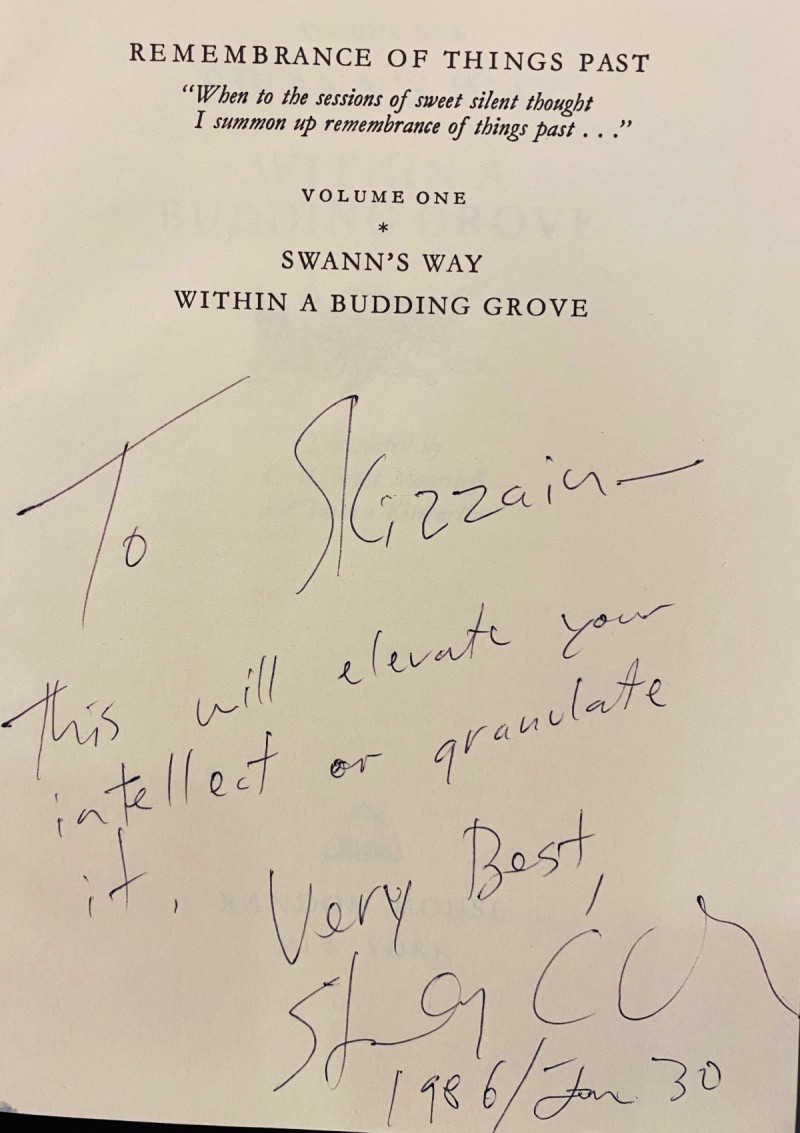

Stanley was from the hood, and he had all of the grit and mother wit that came with that pedigree. He was also a home-grown intellectual genius of endless curiosity with abundant ability to make deeply insightful macro AND micro observations. He loved to investigate all kinds of things and was always telling me, “Go see this (Goya) or that (Romare Bearden),” or “Go hear this (Cecil Taylor) or that (Joe Morello),” or “Read this (Jazz Modernism) or that (Leon Forrest’s Divine Days).” Interestingly enough, over time I realized that many of the pieces and ideas he suggested checking out were contrary to his own tastes and philosophical attitudes. He would always say, “Check it all out. Earn your own prejudices, man.” That was also my daddy’s philosophy, so it was easy to understand where he was coming from.

“Crouch” (I called him by his last name, and he called me by mine) held a Ph.D. in connecting and assimilating an unimaginable diversity of information across time, space, culture, and conception. Years ago, upon viewing a televised Olympic equestrian event, he started talking about training horses, which led him to remember the introduction of Iberian horses to the New World, then on to the Spanish Inquisition, right into the intrinsic value of gold, which inspired a rumination on 16th century European battle tactics, leading to an exposition on the Incas’ mythological beliefs and their relationship to Christianity, which caused him to speculate on the Catholic Church’s expunging of its own mysticism that actually had a fundamental connection with the Incas’ mythology (even though Incan beliefs failed them in confronting Pizzaro), but after all, the Church had also failed important central elements of its basic purpose by employing fetishes and pagan rituals that became a cheap form of popular entertainment but drew such large, enthusiastic crowds that the religion eventually gave up on enlightenment and eventually had to settle on enlisting guilt and shame to control people, but on further examination, not all shame was bad because the absence of remorse leads to runaway criminality, and that’s what was going on in Pendergast’s Kansas City when Charlie Parker was a kid, you see, when an empowered group of elites fails to police themselves, they unleash an unrepentant decadence (like when Pizarro and the Conquistadors started greedily killing each other over who got what of the undreamt-of spoils they had successfully plundered), and that corruption was at the root of the Church keeping priests from getting married so they couldn’t own land, and that the hypocrisy of a religion accruing wealth in the name of a Savior who took a vow of poverty was coming home to roost on them now, and that, actually, Charlie Parker’s mother was maybe having an affair with a married preacher and this broke young Bird’s heart and spoiled his relationship to religion but didn’t affect his talent because spirituality is so much deeper than religiosity, and that the Incas could not overcome traditional tribal hatreds to amass a sufficiently large army and could not adjust their conventional battle tactics to defeat the superior technology of the Conquistadors, and how internecine fighting and jealousy against Dr. King is what caused the Civil Rights movement leadership to disintegrate, and that’s why people my age (who were children at the time of the movement) needed to develop a personal understanding of what derailed the movement, because you will end up defining your experiences with the enemy’s narrative—like the South lost on the battlefield but won the political fight and reversed the gains of the Civil War, returning black people to peonage for the next hundred years, and then they infected popular culture with nostalgic propaganda pieces like Birth of a Nation (which you need to look at again)—and that culture is even more hotly contested because it determines WHO people will be, and did I know any military bugle calls that were played in the Civil War, and do I understand the relationship of the trumpet and drums to war and how difficult it must have been to play a bugle in a battle, and then a rumination about Buffalo Soldiers and the Rough Riders and how your behind feels on a saddle after too many long hours, and do I know any Mexican trumpet players? To which I responded, “Yes, Rafael Mendez. He was one of the greatest ever and as a kid, played for Pancho Villa.” To which HE laughs and says, “You see? That’s why you can’t play, you’ve never played under the life-or-death heat of battle.” And I had to laugh because all of that was literally said in three minutes immediately following looking at the kind of equestrian event that he said he never watches.

Well… that type of extended solo was natural to HIM, but to witness it over and over again, with subject after subject, was unforgettable. Stanley was also the first one to say, ”Let’s go visit so-and-so in the hospital,” or “Make sure you call so-and-so who lost someone,” or “Send some flowers to Miss so-and-so,” and, repeatedly, he showed up for someone in our community who was having a tough time. But we don’t have to put sugary icing on him as he takes the long journey down the short road; he wouldn’t have wanted that. Unlike you and me, he was not perfect—not by a long shot—but he was always present… and always in pursuit of deeper and more enduring human meaning. I hope, if he is still pursuing it, that he finds it.

Stanley Crouch was a writer and a poet of uncommon depth and feeling. Don’t listen to what is said about what he was saying. Read him if you want to know him. When I was a kid, he used to tell me, “Learn stuff for yourself. Don’t take other people’s opinions because you might end up slapping yourself… and won’t even know that’s what you’re doing.”

Crouch once played a tape of his drumming for me when I was 18 and asked what I thought. I didn’t know it was him, and said, “It’s sad. I mean… it’s creative, but my man can’t really play.” After a while, he said, “That was me playing.” I replied, “It’s even sadder than I thought then,” and we both really laughed. Hard. That was over 40 years ago.

Wynton