Wynton’s interview at Tavis Smiley Show 2004

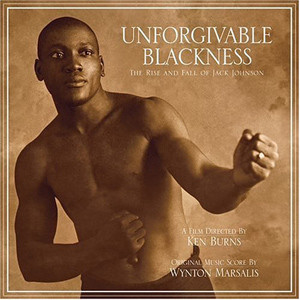

Tavis: I’m delighted to welcome the great Wynton Marsalis to this program. The acclaimed musician, composer and bandleader is the artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, the largest not-for-profit arts organization dedicated to jazz music in all the world. He also serves as the composer for the latest Ken Burns documentary, ‘Unforgivable Blackness.’ The film airs in January right here on PBS. Ahh! If that wasn’t enough, in 2 weeks from now, he debuts his latest piece called ‘Suite for Human Nature,’ which will be performed in Washington, D.C., December 10 through the 12, and back in New York December 16 through 19. Wynton Marsalis joins us tonight from New York. How he found the time, I do not know, but it’s nice to see you.

Wynton Marsalis: All right. It’s good to talk to you.

Tavis: Nice to talk to you. I forgot you’re on a satellite feed, and I wore the nicest, jazziest tie tonight with so much beautiful color in it. You can’t even see this thing, man.

Marsalis: Man, look, I thought I was going to see you in person, too. I got clean. I got my little pocket—I don’t normally have this. I put my square in. I got everything. I said I got to be right for Tavis.

Tavis: Well, we both got clean for each other. Anyway, I’m delighted to see you and happy holidays, Wynton.

Marsalis: All right, man. It’s great to talk to you.

Tavis: I have called you already the great Wynton Marsalis. Early in the introduction, I referred to you as a legend in your own time. You ever get uncomfortable about all these accolades? Do they put a certain amount of pressure on you to come stronger even than you’ve already come these years?

Marsalis: No. You know, you get accolades and you get cut down, too.

Tavis: Ha ha ha!

Marsalis: You get a nice mix. A lot of my pressure is internal. I want to do these things. I want to create things. It’s like I’m compelled to do it. And I just feel fortunate to have the opportunity to do it.

Tavis: Well, you say your pressure is internal. I think I know what you mean by that, because I can wax poetic about that myself in how I process my own life, but this ain’t about me, it’s about you. What do you mean when you say that you have internal pressure that you place on yourself?

Marsalis: Well, I want to—I just want to develop my musicianship. I love creating and coming up with things. You know, a lot of times, especially when you’re writing music like the ‘Suite for Human Nature’ that I’m writing, the music comes to me at night, so when I wake up, I have to write it down. I don’t really have a choice. And I can’t stop it from coming. There’s nothing else I would rather be doing, so it’s not hard for me to stay up maybe for 2 weeks or 3 weeks and write around the clock or any of this stuff, man, teaching or playing the jam sessions or practicing. This is something that I’ve done since I was 12 years old really pretty much steadily, so I’m kind of driven to do it.

Tavis: You know, I love you and I love your gift and I was a little concerned earlier this summer when I learned that you were pushing yourself so hard that your lips swole up. And your doctor told you to sit down and shut up.

Marsalis: Well, it wasn’t me, it was my piano player, a guy named Eric Lewis. We call him the top professor.

Tavis: Right.

Marsalis: And he goes out and finds a place to play every night somewhere, so we were on tour and I was playing like quartet gigs and we would play all kind of wild, high stuff all night. Then after the gig, he and I would go find a jam session anywhere in any city and then we would end up playing till 3:00 and 4:00 in the morning, 4:30, then getting up again at 7:30, 8:00 and doing the same thing. You know, piano is not like trumpet, man.

Tavis: Ha ha ha!

Marsalis: Piano and them saxophone players, they could play all night, but this trumpet, mmm, it’s like a baseball pitcher’s arm or something. You got to be very careful with it.

Tavis: And, Wynton, with that kind of schedule, when did you find time to squeeze in a game of b-ball?

Marsalis: Man, I was playing a little bit. You know I’m getting to that age where I stand around a lot on the court.

Tavis: Ha ha ha!

Marsalis: I don’t do too much running.

Tavis: Yeah, you and me both these days. You mentioned jam sessions a moment ago. When you were on the road, your piano player would find these places for you guys just to drop in unexpected. And what a treat it must be to be in a club or to be at a restaurant and out of nowhere, unscheduled, Wynton Marsalis walks in and just starts jammin’. Now, I’m told, and I’m coming to New York next week ‘cause I’ve not seen the new house that you built, Jazz at Lincoln Center, but I’m told that you have a jam session set up in the building where people just drop by and do their thing. I’m told on top of that that Stevie Wonder was in town the other night and you and Stevie just got together. But tell me about this place inside the Center, so I need to stop by there.

Marsalis: Well, it’s a club. It’s called Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola, and the club is named for Dizzy. Coke put up the money to name it for Diz and we try to keep the spirit of Dizzy in the room. You know, Dizzy was always around the world playing with a lot of different people. He was fun-loving. And it’s open 365 days a year. It’s 140 seats. People really seem to love the club. The other night Stevie and I got together. We went to the club. He had his harmonica and he said he wanted to play Lionel Hampton’s tune ‘Midnight Sun.’

Tavis: Mmm!

Marsalis: And he got up and played. You know, we have a hang set every night after the group that’s playing plays. There’s a duo or a trio, but musicians, they play till 2:00, 3:00, 4:00 in the morning, however late people come. We serve food, soul food. We got all kind of collard greens and gumbo and stuff that you feel. We’ve got a great hamburger there, too. You know, we wanted a good hamburger. Just very basic. We got even some stuff for vegetarians, you know? Whatever. Mainly we got people in there swingin’ every night.

Tavis: Yeah. I can’t imagine, again, what it must be like to just be hangin’ there and Stevie and Wynton just walk in and start hittin’ it.

Marsalis: Well, it was somethin’. It was a trip really, because, you know, we were just— A good friend of ours named Lisa Hoggs had put us together, and she used to be Stevie’s assistant. So we were talking and Stevie said he wanted to hang, he wanted to come check out the halls and the spaces. And even after we played in a jam session, then he asked me to take him around. I took him into the 1,200-seat theater and the 600-seat room. He sat down and played some of his songs, ‘The Secret Life of Plants.’ That’s one of my favorites with the nice harmonic progressions, and then he went to the 600-seat room, and he went to the studio and he was very invigorated by it. He said he really enjoyed playing. And of course the people in the club, they were going crazy when he got up and started playing.

Tavis: I’m sure. You’ve already started to give me a little tour of what the new building looks like. Let’s pick up on that and get you to tell me a little bit more about this new Center that you have built.

Marsalis: Well, the Center that we built is based on integration of the arts and integration of ages and cultures and just really bringing things together, so we have different types of spaces. We have a 1,200-seat room which is based, kind of loosely, on the feeling of an Italian opera house—small Italian opera house meets the Globe Theatre—which means we have people close to us and it’s stacked high. It has a wonderful kind of golden sound to it. We have these columns that can be moved and it accommodates film. We’ve already done a film presentation with Ken Burns. And it accommodates dance. We had a great dance program with Garth Fagin and with Elizabeth Streb and with Savion Glover.

And the 600-seat room is called the Allen room and it faces out onto Columbus Circle and it’s based on the feeling of a Greek amphitheater. It’s kind of like a Greek amphitheater meets Japan, because it’s form and function in one. And this is our community room. We can have public dance there. We had a great concert playing Duke Ellington’s ‘Black Brown and Beige’ and Benny Carter’s ‘Kansas City Suite.’ We had a great Brazilian night with Hermeto Pascoal, and Cyro Baptista came and played and the people dancing and going crazy over their music that they love so much.

We have a studio, state-of-the-art studio, one of the second or third largest rooms in New York, which has, once again, we’re going for that kind of golden bloom in the sound. We also rehearse there, and it’s large enough to accommodate an orchestra.

Tavis: Mmm!

Marsalis: So that’s the major spaces we have in addition to the club.

Tavis: I’m not gonna call you anal like my friends call me. I prefer the word perfectionist, if I must be called something. So I’m not gonna call you anal, Mr. Marsalis, but I will call you a perfectionist. And so it did not surprise me—I don’t know which of these stories are true, but I’ve heard a number of stories from a number of folk involving this process of how intimately involved you were— trying to put it nicely—how intimately involved you were in this thing getting built. I heard you were down on the floor, looking at wood grain. I heard that—well, you tell me how involved you were in making this thing the way you wanted it to be.

Marsalis: Well, I was involved in it, but, you know, I like to work the people, and I don’t stay on top of people and ride them because I always feel like they know their job much better than I would know it. And my job was mainly to be very clear about the mission and the vision of everything. So in terms of micromanaging, I don’t know about that. I stay out the way. I just…we’re lucky with the great team of people we put together, and, you know, acousticians are gonna know much more about acoustics than I’ll know. Our great architect, Rafael Vinoly, he’s…no way I know anything about architecture. I just…the main thing that my direction was, that all the people we worked with gave me a very clear direction, ‘Tell us what you need and be very clear about it. The less speculation we have, the better.’ And I know from writing ballets and stuff, working with other people, the clearer someone is with you, the easier it is to do your job. And we were fortunate on this particular job because everybody really wanted to do it, and they worked far beyond the call of duty because we all had the feeling that it was something historic, and we wanted to put our best foot forward for the world. We want everybody to come to this space and say, ‘Man, it feels good up in here.’

Tavis: Let me ask you how pleased you are with the sound that has now been achieved, and I ask that against the backdrop of this. I was at a concert not long ago. Aretha Franklin, the queen, had not been in L.A. in 20-some years and came out here a little while ago to do a series of concerts in L.A. And I went to hear her one night out here at the Greek, and I thought the queen was sounding awfully good. But she kept talking to the soundman out loud, of course, on the microphone, telling him what to do here, what to do there, and she wasn’t getting what she wanted. And, as you might expect with a diva like the queen, she said, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, hold on one second. I’ll be right back.’ She left the stage, went and had a conversation with the soundman, came back, and the sound sounded infinitely better. I could tell in my own ear. It sounded so much better than it had, and I thought she was sounding good to begin with. So you guys know what you’re looking for. That said, does it sound—are you hearing what you wanted to hear?

Marsalis: Definitely. You know, we’re tweaking a few little things, but I think that the acoustical team did such a—did an unbelievable job. I mean, they got so close to what we wanted, we’re so happy about it—I’m so happy about it, I don’t really know what to say. I just hug ‘em, you know? And, I mean, we worked with each other. We’ve seen each other all over the world in different halls. We’ve talked about these halls for years, and about other halls that we like, and, really, some of us on the team, we’re like brothers. I mean, I played at one of our acousticians’ wedding the other day, so, you know, it’s like the type of thing where you get together. And I always tease him ‘cause he’s a little younger than me, and I said, Man, you had been my little brother, I’d have beat you up.’

Tavis: Ha ha ha!

Marsalis: But they did such a fantastic job that, uh, you know, we really are ecstatic about it. And all the musicians who have come in to play have said, man, it’s unbelievable.

Tavis: Let me flip it on you right quick, Wynton. I have spent the better—at least half of our conversation time on this program tonight talking about all the money and all the energy and all the effort and the wonder and splendor of what has been built now in this new facility, Jazz at Lincoln Center, and yet, we live in a world, certainly in a country, where jazz, many could argue, I think, legitimately, is not valued in the way that it should be. Indeed, jazz, the only art form that we, America, gave the world, black folk gave it to America, and yet we don’t value it in the way we should. Juxtapose for me the lack of value and appreciation we have for jazz and why you’re investing all this energy into doing what you’re doing.

Marsalis: Because jazz, because it’s our definitive art form, it lets us know who we are as Americans. And, you know, race has always been one of our problems, but each generation, it’s our job to heal a little more, and to say, OK, we’re gonna move it forward a little bit. At Jazz at Lincoln Center, that’s what we try to do. We try to bring all the musicians in.

We try to recognize the music and bring all of the traditions together. It could be the tradition of Benny Goodman, Bix Beiderbecke, Artie Shaw. It could be Duke Ellington, Count Basie. We try to say all of this music is together, and for the many of us that work together that are the sons and daughters of musicians, like a good example is in our band. My father is a musician, and Ted Nash, who is white, is one of our saxophone players, his father’s a musician. And we’re doing a show called ‘Speaking about Jazz,’ where we took civil—we took human rights speeches and we put it to music. And when we got to Lyndon Johnson’s speech—We got different people to commission them to write the music—When we got to Lyndon Johnson’s speech, after that speech was over, Ted and I saw each other backstage, and he was full. He started tearing up. He said, ‘Man, this is our tradition.’ And, you know, this is our thing that he and I talk about all the time. What are we gonna do to continue the work of the Civil Rights movement and to continue to come together as musicians, as people, as human beings, and to set a higher standard?

Lot of times in our country, it’s just really a lack of education. People don’t want to be ignorant. They don’t want to have an ignorant response and to hate each other. But when you’re responding to a tradition of ignorance and of hatred, and you don’t have the type of leadership that has a component of education to it, what can you do? You know, you fall into these groups, and the divisiveness and the divisive things are used as a commodity. They’re used to sell you ideas, to cheat you out your money, to keep you behind, and we in the arts are always about defining things accurately. That’s why art forms remain when governments fall. The Greek civilization as we know it has been gone, but we still can check out the ‘Odyssey’ and the ‘Iliad.’ The middle ages have passed long into dust, but we still are checking out Shakespeare. Bach, the baroque era’s been, we still have Bach’s music and Beethoven and so on. We can go through the history of the arts.

Tavis: Mmm! I was fascinated. I was gonna say go on, man. You were rolling so good, I didn’t want to interrupt you there.

Marsalis: Man, I don’t want to soapbox, you know. I’m just trying to be clear.

Tavis: I’m glad you said that because, speaking of soapbox and your statement specifically that you don’t want to soapbox, there were many who—I recall this like it was yesterday—1988, when you wrote that piece, 15 years ago now, and you wrote that piece in the New York Times about what jazz is and what jazz isn’t, you caught pure hell then. And you go to the right place in the right circle, you still catching hell for what you wrote 15 years ago about trying to define what this art form was, or is, as you see it. Take me back 15 years ago to what you had to say and whether or not you think anything’s changed since then.

Marsalis: No, you know, I stick pretty much to my viewpoint, and I don’t mind catching hell for it because, in a way really, I enjoy it. I wish I could catch a little more in person. Lot of times, you show up, everybody’s smiling. You know, I…I feel it’s my responsibility to speak in a clear voice and not to allow constituencies or whatever it is to affect—I’ve studied this art form. I love it. I know about it. I’m relatively knowledgeable on it, and I don’t mind expressing what my opinion is on it, recognizing it as one of many opinions that are heard. But I’m not gonna be a coward because the majority viewpoint— actually, the majority viewpoint on jazz doesn’t even come from musicians, so I don’t feel like, uh… I feel like maybe sometimes you say something, people get mad, but it’s not anything—it’s not invective, or it’s not personal. It’s just out of the desire for clarity and to make sure that we can get some younger musicians who can play, and that they have good information, or at least they have an alternative, so they can look around and say, ‘Well, what about this?’

Tavis: With regard to what you had to say 15 years ago as compared to today, is the art form still being bastardized more or less than it was 15 years ago?

Marsalis: Well, you know, as always, there’s a level of just commercialism that’s run rampant in our culture—lack of integrity. You know, we see it all the time. And, uh, what can I say about it? I mean, it speaks pretty much for itself. And our art form is no different, but there are always more and more people who are interested, just like in our country. We might see the one film clip where somebody’s showing their behind, but there are hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people who go to work every day who are concerned—not if not millions, there are millions of people who go to work every day concerned for their kids, who are trying to do something to bring people together, but, you know, it doesn’t get the sound bite. So when I get my sound-bite time, I’m trying to represent those people.

Tavis: Let me ask you whether or not you are— I want to talk to you here. I want to use this question to turn the corner, if I might, to talk about some of the projects you’re working on because there are many that you’re working on as we speak, as I mentioned at the top of our conversation. But as you travel around the country doing all the work you do with young people, to say nothing of the work you’re doing there with the program at Jazz at Lincoln Center, are you encouraged? Is there reason to believe, to be hopeful about the future of jazz?

Marsalis: I’m hopeful about the future of our country. The problem is not the younger people. The problem is the people my age and older. Young people are beautiful, you know? And when you come to the young people with some love and with some information and with consistency, they respond to it. I don’t care where they come from, ‘cause I go all over the country. Any economic group or whatever the clichés are we tend to deal with people in terms of, but the problem is when you start trying to exploit them, exploit their sexuality, exploit their disposable income, exploit…then you turn around and say something is wrong with them. There’s no problem with the young people. The young people are bright, they want a better future, they see things that are wrong, but young people need guidance and they need education.

Tavis: Let me throw some titles at you. These will be titles of some of the projects you’re working on and just let you share with me what you’re doing under these banners. We mentioned this already. ‘Suite for Human Nature.’

Marsalis: Right. The ‘Suite for Human Nature’ is a piece written by Diane Lampert and it’s like a tale for kids, and it gives us a wonderful chance to look into something about human nature. We have different characters. Mother Nature and Father Time get together and they have some children and one is Greed, one is Envy, one is Hate, all the kind of negative things, Fickle…and then we’re introduced to the 4 seasons: Summer, Spring, Autumn, Fall. They leave their kids with the humans, and the humans catch the characteristics. And then the winds get together in the second half and say, ‘Hey, you need to make your kids more like me, the West Wind, more like the South Wind, more like the North Wind, more like the East Wind,’ so on and so forth. And then they come up with twins and these twins are called Love. And Love is so inconspicuous and it’s such a wonderful, adaptable thing that all the kids start to be able to get along with it and play with it. And, you know, it proceeds along those lines and there’s a lot of jazz in it, great singing. And it’s the Harlem Boys Choir, Boys Choir of Harlem is gonna be singing. It’s a wonderful thing for the family to get in touch with jazz in a benign way.

Tavis: I don’t know where to begin in terms of asking about all the varied educational programs for young people that you have underway with regard to Jazz at Lincoln Center, but let’s start somewhere.

Marsalis: Well, we got one coming up this weekend. It’s one of our ‘Jazz for Young People’s’ concerts. We’ve been doing this for 12 years and this one is called ‘The Big Picture,’ and it’s going to deal with visual arts, with artists, and how their contributions are related to jazz and how their elements of artistry, of painting that relate to elements of jazz. Things like syncopation, rhythm. We’re gonna be looking at the artwork of Matisse, Norman Lewis, Romare Bearden, the photography of Roy Decarava, of Chuck Stewart, of Frank Stewart. We’re gonna see some pieces of Stewart Davis and we’re gonna look at the pieces. We’re gonna put ‘em up on a big screen, play some music. We’re gonna talk about all these different things and all this to the backdrop of families and the kids that are gonna be in there like they always are, makin’ the little noise and lookin’ at that and… You know, I love doing the Jazz for Young People’s concerts because they’re so informal and fun and they have a high content.

Tavis: I always think I’m disciplined until I find myself in conversation with you, ‘cause I gotta work a little harder, man, ‘cause you be puttin’ it down so tough. This documentary, the Jack Johnson piece that’s gonna air on PBS here after the first of the year by Ken Burns, a great filmmaker as we all know, you did the score for the documentary.

Marsalis: I did the score. We also just did a program at Lincoln Center at the Frederick P. Rose Hall, and Ken made a presentation. I just want to say I have such tremendous respect for him and respect for his genius. You think we work hard or we’re organized, man, you ought to see him. When I knew his show was coming, I breathed a sigh of relief, man. I say, ‘Well, now I’m not gonna have to do anything,’ and, man, he laid out everything for me. ‘I want the cues here.’ We talked a little earlier about the acousticians and architects and importance of being very clear about what you want. Man, Ken Burns is so crystal clear, it’s like you lookin’ into the future, so it was an honor for me to work on this film, of course, about the great Jack Johnson. It was written by Geoff Ward who’s Ken Burns’ great collaborator. It just deals with Jack Johnson’s life. Man, it’s unbelievable the stuff that he did. He had a lot of heart.

Tavis: Yeah, I got about a minute to go here. I’m not sure this is a fair question, but I’m sure you can handle it. In the context of everything that you want to do or everything you think you are gifted and talented by God to do, where are you on your journey at this point? Are you halfway there? I mean, where are you at this point? How good are you at this point?

Marsalis: You know, I feel like I’m just starting, like, my whole thing is just to bring people together, and you know, I feel like I’m just starting out. I feel like a baby out here. I tell my sons that all the time. Man, I look like my own son out here.

Tavis: Are you having fun? I think you are. You look like you are.

Tavis: Man, you know, what can I say? I can’t complain. What can I say? I don’t want to jinx myself.

Tavis: Well, we don’t want that to happen, either, ‘cause the stuff you are doing is so special and so wonderful and so good, I don’t want to do anything or say anything or set you up to say anything that might in any way jinx what you are doing. Wynton Marsalis, I tell you, as you well know, I am proud of you, delighted to have you on this program, humbled, in fact, to have you on this program and appreciate all the work that you are doing not just for our people, but for people all over the world.

Marsalis: Well, man, I appreciate that and I’m proud of you, too, man. I love you what you’re doing, you know? I don’t want to sound like mutual admiration, but really.

Tavis: I appreciate it. Nice to have you on. All the best to you. All right. That’s our show for tonight. As always, you can catch me on the radio on NPR, National Public Radio. I will see you back here next time on PBS. Until then, thanks for watching, good night from Los Angeles, and as always, keep the faith.