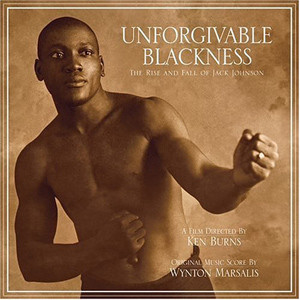

Unforgivable Blackness – The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson

Trumpeter Wynton Marsalis’ soundtrack to Ken Burns’ documentary Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson is a compelling and rootsy mix of blues and swing. Having worked with Burns on the PBS “Jazz” series, Marsalis’ Unforgivable Blackness soundtrack seems like a natural progression of a fruitful partnership. Not dissimilar to such past Marsalis projects as the Jelly Roll Morton album Mr. Jelly Lord, the album features Marsalis in various small-group settings along with such longtime Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra regulars as drummer Herlin Riley, pianist Eric Lewis, saxophonist Wessell Anderson, bassist Reginald Veal, trombonist Wycliffe Gordon, and others, including guitarist Doug Wamble, who adds his unique blend of old-time blues, folk, and jazz to Marsalis’ own signature updating of ’20s and ’30s jazz. Although four previously released tracks appear here, two off Standard Time, Vol. 6: Mr. Jelly Lord and two from Marsalis’ Reeltime, the majority of the album is newly recorded and all of it sounds of a piece. Ironically, Marsalis’ deepest musical influence and aesthetic nemesis, trumpeter Miles Davis, also recorded an album for a film about the troubled boxing champ Johnson, 1970’s fusion classic Tribute to Jack Johnson. However, where Davis’ album seemed to reflect the counterculture and Black Power movements of the time, Marsalis is more traditionally cinematic in his approach, with each track evoking the pride, urbanity, strength, and tragedy of the legendary Johnson.

Album Info

| Ensemble | Multiple Ensembles |

|---|---|

| Release Date | November 30th, 2004 |

| Recording Date | September 3, 2003 |

| Record Label | Blue Note Records |

| Catalogue Number | 7243 8 64194 2 2 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| What Have You Done? | 1:58 | Play |

| Ghost in the House | 5:05 | Play |

| Jack Johnson Two-Step | 1:37 | Play |

| But Deep Down | 0:50 | Play |

| Love & Hate | 1:41 | Play |

| High Society | 1:22 | Play |

| Careless Love | 2:12 | Play |

| New Orleans Bump | 4:34 | Play |

| Trouble My Soul | 3:32 | Play |

| Deep Creek | 5:14 | Play |

| Johnson 2-Step | 2:37 | Play |

| Rattlesnake Tail Swing | 2:32 | Play |

| Weary Blues | 3:19 | Play |

| Troubles My Soul | 3:20 | Play |

| Johnson Two-Step | 1:56 | Play |

| Fire in the Night | 3:27 | Play |

| Morning Song | 2:48 | Play |

| I’ll Sing My Song | 1:17 | Play |

| Buddy Bolden’s Blues | 1:21 | Play |

| Last Bell | 2:47 | Play |

| We’ll Meet Again Someday | 4:32 | Play |

Liner Notes

Any serious study of American history inevitably engages the question of race and the monumental hypocrisy born at our founding; the existence of slavery in a country that had just proclaimed to the world that “all men are created equal…” In the story of Jack Johnson, these questions come to a profound crux. This is not just a story of supreme athletic achievement, nor even just a story of sex – black and white sex – which got Johnson into so much trouble. It’s not even wholly about race, though Johnson’s “unforgivable blackness” propels this extraordinary story. In the end, this is a story about freedom, and one black man’s insistence that he be able to live a life nothing short of that of a free man.

- KEN BURNS

Walpole, New Hampshire

April 16, 2004

Jack Johnson may or may not have been the best heavyweight of all time. Boxing historians differ. But there can be little doubt that he was the bravest: every time he triumphed over a white opponent one or another of the howling white fans who had paid to see him beaten might easily have killed him.

But he was always far more than just a fighter: At a time when whites ran everything, he took orders from no one and resolved to live as if color did not exist. While most African Americans struggled merely to survive, he reveled in his riches and his fame. And at a time when the mere suspicion that a black man had flirted with a white woman could cost him his life, he insisted on sleeping with whomever he pleased – and for that “crime” was persecuted and driven into exile by his own government.

He was in the great American tradition of self-invented men, too, and no one admired his handiwork more than he did. “My life,” he wrote, “almost from its very start, has been filled with tragedy and romance, failure and success, poverty and wealth, misery and happiness.”

The music for Unforgivable Blackness, written or rearranged by Wynton Marsalis and beautifully played by him and an all-star group, captures more of the richness and complexity of that life than I would have thought possible. It’s all echoed here: the high-stepping sporting world that was Johnson’s real home and the perpetual threat of racial retribution he faced each time he dared to move outside it; his epic battles in the ring and the intelligence and sensitivity that lived behind his celebrated golden smile; the tragedy of his first, doomed marriage and the unconquerable spirit with which he always seemed to surmount his trouble.

Music meant a lot to Jack Johnson. He never traveled anywhere without his big wind-up Victrola and the stack of operatic and symphonic records with which he liked to play along on the bass viol that was also a permanent part of his luggage. Ragtime fueled the nonstop fun at the Café de Champion, the opulent Chicago nightclub he ran for black and white patrons during his heyday as heavyweight title-holder, and in leaner times during the 1920s he sometimes appeared with his own jazz band. And so I suspect Johnson would have found the soundtrack for Unforgivable Blackness as irresistible as I do. It swings. Much of it is built around the blues, the musical embodiment of the triumph over adversity that Johnson exemplified throughout his life. And best of all, from Johnson’s point of view, it is all about him.

-GEOFFREY C. WARD

Scriptwriter for the film and author of the biography, Unforgettable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson

UNFORGIVABLE BLACKNESS

THE RISE AND FALL OF JACK JOHNSON

Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson tells the story of the first African-American boxer to win the most coveted title in all of sports – the Heavyweight Championship of the World – and his struggle, in and out of the ring, to live his life as a free man in a country in which black people were not yet fully free.

The film follows Johnson’s journey from his humble beginnings as the son of former slaves in Galveston, Texas, to his entering the brutal world of professional boxing, where, in turn-of-the-century America, “the heavyweight championship was the exclusive property of whites: no black challengers were permitted to contend for it.” Despite the seemingly insurmountable odds, Johnson battered his way up the heavyweight ladder and along the way emerged as a controversial national sports figure, indulging himself fully in the bawdy life of “the sport” and becoming increasingly bold in his personal life – openly courting and traveling with white women despite public outrage, death threats, and sharp criticism from black accommodationists, including Booker T. Washington.

Johnson’s skills had made him the leading contender for several frustrating years before the champion, Tommy Burns, finally gave in under unexpected pressure from elements of the white sporting press and granted him a shot at the title. On December 26th, 1908, in Sydney, Australia, Johnson demolished Burns before a crowd of 20,000 stunned spectators, to win the title at last.

Johnson’s victory over Burns was seen as a national disaster by many whites, and set in motion a worldwide search for a “Great White Hope” who could return the heavyweight title to the white race. Jack London, who covered the fight for The New York Herald, was one of the first to publicly sound the alarm, ending his article with a plea:

“One thing now remains. Jim Jeffries must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove that golden smile from Jack Johnson’s face. Jeff, it’s up to you.”

London wanted Jim Jeffries, the legendary former champion who had refused to fight Johnson or any other black challenger before retiring undefeated in 1905, to come out of retirement and teach the new champion the new champion a lesson. Under overwhelming pressure from white boxing fans and sportswriters around the world, and convinced of the superiority of the white race, Jeffries answered London’s call and agreed to face Johnson in the ring. On July 4, 1910 in Reno, Nevada, Johnson knocked him out. Nationwide race riots followed.

Following his victory in Reno, Jack Johnson appeared to be on top of the world, having retained his title and achieved even more fame and fortune in the process. But white America was still bitter over his defeat of Jim Jeffries, a bitterness only deepened by Johnson’s refusal to conform to society’s expectations. Now, trouble seemed to follow Johnson everywhere – some of his own making, some stirred up by his enemies. Following in a tradition among champions initiated by John L. Sullivan, Johnson joined a touring vaudeville troupe, but the unrelenting schedule of performances in front of hostile crowds left him demoralized and exhausted. Former business associates filed law-suits against him. And death threats continued to arrive regularly in the mail.

Things continued to go downhill for Johnson. In September of 1912, his white wife, Etta Duryea, committed suicide. In October, he was arrested and charged under the Mann Act, a broadly worded, flawed piece of legislation originally designed to stop white slavery rings. Johnson was specifically charged with transporting former girlfriend, Belle Schreiber, from Pittsburgh to Chicago for the purposes of “prostitution and debauchery.” With anti-Johnson sentiment at an all-time high, it took an all-white jury less than two hours to convict him. He was sentenced to a year and a day in prison. Released on appeal, and realizing that a fair trial would be impossible, Johnson fled the country with his new white wife, Lucille Cameron.

Johnson had once been popular overseas. Now, as a fugitive from justice, he was denied rooms at hotels in Paris. London vaudeville performers refused to take the stage with him. His money was running out, and, with the onset of World War I, boxing was far from the minds of the European public.

A large segment of white America was still eager to see Johnson defeated in the ring, and in 1914, to ambitious promoters began putting together a title fight between Johnson and Jess Willard of Pottawatomie, Kansas. As Johnson could not reenter the United States, the 1915 fight took place in Havana, Cuba. Six feet, six inches tall, and weighing 250 pounds, Willard seemed like a giant. Johnson held his own in the fight, but began tiring in the 20th round, and in the 26th round was knocked out. Willard won the fight – and the title.

After his loss to Willard, Johnson attempted to continue boxing, but he was badly out of shape and his celebrity had faded. At the age of forty-two, he was a man without a country or a home. He tried to make a living any way he could – bullfighting in Spain, wrestling, and acting. Finally, in 1920, out of money, homesick, and tired of running, Johnson surrendered to U.S. authorities in California and was taken to Leavenworth Prison in Kansas to serve his sentence for violating the Mann Act. Even in prison, Johnson tried to live on his own terms. He had Lucille send cigars and consistently flouted prison rules.

Upon his release from prison in 1921, Johnson was optimistic. He immediately challenged heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey – who had taken the title from Jess Willard in 1919 – but Dempsey refused to fight Johnson, or any other black challenger. Throughout the 1920s Johnson tried to stay in the public eye, and in 1927 he published his autobiography. The 1930s saw Johnson taking bit parts in “B movies” and appearing at a Times Square sideshow, telling his version of his life story.

In 1937, Joe Louis became the second black heavyweight champion in history. A popular fighter, Louis was urged by his handlers not to associate with Johnson. Ironically, on his way to see Joe Louis defend his title against Billy Conn in 1946, Jack Johnson died in an automobile crash on a North Carolina highway.

Credits

1. What Have You Done?

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Victor Goines (clarinet); Wycliffe Gordon (trombone); Doug Wamble (guitar); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums); Eric Lewis (washboard).

2. Ghost In The House

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Victor Goines (clarinet); Wycliffe Gordon (trombone); Wessell Anderson (alto sax); Doug Wamble (banjo); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums).

3. Jack Johnson Two Step

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Victor Goines (clarinet); Wycliffe Gordon (trombone); Wessell Anderson (alto sax); Eric Lewis (piano); Doug Wamble (banjo); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums).

4. But Deep Down

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Victor Goines (bass clarinet); Doug Wamble (banjo); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums).

5. Love & Hate

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Victor Goines (clarinet/tenor sax); Wessell Anderson (alto sax); Wycliffe Gordon (trombone); Doug Wamble (banjo); Eric Lewis (piano); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums).

6. High Society

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Victor Goines (clarinet); Wessell Anderson (alto sax); Wycliffe Gordon (trombone); Doug Wamble (banjo); Eric Lewis (piano); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums).

7. Careless Love

(Handy Koenig-Williams / Handy Bros. Music. Co. Inc. / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Wycliffe Gordon (trombone); Don Vappie (banjo); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums).

8. New Orleans Bump

(Jelly Roll Morton / Edwin Morris & Co. / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Dr. Michael White (clarinet); Victor Goines (clarinet/tenor sax); Wessell Anderson (alto sax); Lucien Barbarin (trombone); Wycliffe Gordon (tuba); Don Vappie (banjo/guitar); Eric Lewis (piano); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums).

9. Trouble My Soul

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Victor Goines (bass clarinet); Wycliffe Gordon (trombone); Eric Lewis (piano).

10. Deep Creek

(Jelly Roll Morton / Edwin Morris & Co. / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Dr. Michael White (clarinet); Victor Goines (clarinet/sax); Wessell Anderson (alto sax); Lucien Barbarin (trombone); Don Vappie (banjo/guitar); Eric Lewis (piano); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums).

11. The Johnson 2-Step

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Wessell Anderson (alto sax); Eric Lewis (piano); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums).

12. Rattlesnake Tail Swing

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Victor Goines, Gideon Feldstein, Sherman Irby, Andrew Farber, Wessell Anderson & Sam Karam (clarinets); Eric Reed (piano).

13. Weary Blues

(Artie Matthews / Edwin H. Morris & Co. / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Victor Goines (clarinet); Wycliffe Gordon (trombone); Doug Wamble (banjo); Eric Lewis (piano); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums).

14. Troubles My Soul

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Victor Goines (clarinet/tenor sax); Wycliffe Gordon (trombone); Eric Lewis (piano); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums).

15. Johnson Two-Step

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Victor Goines (clarinet); Wycliffe Gordon (trombone); Eric Lewis (piano).

16. Fire in the Night

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Marcus Printup (trumpet); Victor Goines (bass clarinet); Gideon Feldstein (bass clarinet); Stephen Riley (tenor sax); Eric Lewis (piano); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums); Kimati Dinizulu (percussion).

17. Morning Song

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Doug Wamble (guitar); Eric Lewis (piano).

18. I’ll Sing My Song

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

Eric Lewis (piano).

19. Buddy Bolden’s Blues

(Jelly Roll Morton / Edwin Morris & Co. / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Wycliffe Gordon (trombone); Don Vappie (banjo); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums).

20. The Last Bell

(Wynton Marsalis / Skayne’s Music / ASCAP)

21. We’ll Meet Again Someday

(Gerd Kadenbach / Di Music / ASCAP)

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet); Victor Goines (clarinet); Wycliffe Gordon (trombone); Doug Wamble (guitar); Reginald Veal (bass); Herlin Riley (drums); Eric Lewis (piano).

Produced by Delfeayo Marsalis, Ken Burns, and Paul Barnes

Recorded at Right Track Studios September 3, 2003

Engineered by Sandy Palmer

Mixed by Jatty Q. Smith @ Glenwood Studios, Burbank, CA, except:

Tracks #7 & 21 recorded @ the Calvin Theatre, Northampton, MA • Produced & Engineered by Jalmoose

Mixed by Jatty Q at Signet Soundelux, Los Angetes, CA

Tracks #8 & 10 originally released on Mr. Jelly Lord Standard Time Vol. 6 ℗© 1999 Sony Music Entertainment • Produced by Steve Epstein • Engineered by Todd Whitelock • Recorded on January 13, 1999 at the Grande Lodge of Masonic Hall, New York. NY – Mixed at Sony Studios, New York, NY

Tracks #12 & 16 originally released on Reeltime ℗© 1999 Sony Music Entertainment • Produced Delfeayo Marsalis • Engineered by Patrick Smith • Recorded in September 1996 Warner Bros. Soundstage, Los Angeles, CA • Mixed Manhattan Center Studio, New York, NY & Signet Soundelux, Los Angeles, CA

To obtain more wood sound from the bass, this CD was recorded without usage of the dreaded bass direct.

Florentine Films would like to extend special thanks to the following people for their help on the music for the film and CD: Sarah Botstein, Peter Miller, Erik Ewers, Jeff Jones, Tom Evered, Tom Levy, Esq., Daniel J. White, Sean Huff, Ryan Gifford, Lynn Novick, Teese Gohl, Christopher Loren Ewers, and David Schaye.

Wynton would like to thank Ed Arrendell, M. J. Hassan, Esq., Genevieve Stewart, Isobel Allen-Floyd, and Dennis Jeter

A film directed by KEN BURNS

Written by GEOFFREY C. WARD

Produced by DAVID SCHAYE, PAUL BARNES, KEN BURNS

Edited by PAUL BARHES (Episode One), ERIK EWERS (Episode Two)

Original music composed by WYNTON MARSALIS

Cinematography: BUDDY SQUIRES, STEPHEN MCCARTHY

Associate Producer: SUSANNA STEISEL

Coordinating Producer: PAN TUBRIDY BAUCOM

Narrated by KEITH DAVID

Voice of Jack Johnson: SAMUEL L. JACKSON

Produced in association with WETA Washington DC

Executive in charge of production for WETA: DALTON DELAN

Project Director for WETA: DAVID S. THOMPSON

Associate producer for WETA: KAREN KENTON

Publicity for WETA: DEWEY BLANTON

SHARON ROCKFELLER, WETA President & CEO

A production of FLORENTINE FILMS

Executive Producer: KEN BURNS

© 2004 The American Lives Film Project, Inc. All rights reserved.

Funding provided by:

General Motors Corporation, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, Rosalind P. Walter, Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Public Broadcasting Service

Personnel

- Doug Wamble – banjo, guitar

- Wycliffe Gordon – trombone

- Reginald Veal – bass

- Wess “Warmdaddy” Anderson – alto sax, sopranino sax

- Eric Lewis – piano

- Herlin Riley – drums, tambourine

- Victor Goines – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet, bass clarinet

- Dr. Michael White – clarinet

- Lucien Barbarin – trombone

- Don Vappie – banjo, guitar

- Gideon Feldstein – baritone sax, bass clarinet

- Sherman Irby – alto sax, soprano sax, clarinet, flute

- Andy Farber – tenor sax, clarinet

- Stephen Riley – tenor sax

- Kimati Dinizulu – percussion

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Buddy Bolden’s Blues - Wynton Marsalis with Dr. Michael White

-

Videos

Videos

What Have You Done (rehearsal) - Wynton Marsalis Septet at Jazz in Marciac 2007

-

News

News

Video: Wynton Marsalis Septet rehearsing in Marciac 2007

-

News

News

Photo: The Wynton Marsalis Septet plays at Marciac 2007

-

News

News

Unforgivable Blackness is now available on DVD

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis’ Unforgivable Blackness is in stores now !

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis’s Glancing Blow

-

News

News

Wynton’s interview at Tavis Smiley Show 2004