Wynton Marsalis on his animal ballet, teen funk band days, kazoos and JALC’s 31 years

Before Wynton Marsalis mastered all that jazz — and more than 40 years before he debuted “Spaces,” his 2016 Jazz at Lincoln Center “animal ballet” now headed to San Diego — he cut his teeth playing in several New Orleans funk bands in the 1970s.

It was then, as the teen-aged trumpeter in such groups as The Creators and Killer Forces & The Crispy Critters, that this 1997 Pulitzer Prize-winning composer and band leader learned some of the key skills he has drawn on ever since.

“Definitely!” affirmed Marsalis, 56, whose subsequent musical collaborators have ranged from Ray Charles and Bob Dylan to Dizzy Gillespie and Carole King.

“I learned what songs to play when, what solos to play, what an audience was like, what kind of stage costumes to wear, what was effective and what was not. We were writing new horn parts and I was putting new bass lines on songs. You learned to be efficient. And people would let you know how you were doing. The crowds were very interactive.”

Did the trumpeter, who was typically the youngest member in those Big Easy funk bands, also do dance moves while playing?

“We did all that kind of stuff, man. We even did ‘The Guillotine’!” he replied. “We also played a lot of slow songs and had a very large female following. One begot the other! We played ’70s funk by Earth, Wind & Fire, The Commodores, some War, P-Funk, Ohio Players, Maze, Stevie Wonder, stuff by Jeffrey Osborne’s group, Ltd., sometimes songs by the Funky Meters.

“Mainly, we did covers of songs that were really popular. A song like P-Funk’s ‘Flashlight,’ we might have played 2 million times, or Stevie’s ‘Sir Duke.’ We did a lot of things from his ‘Songs in the Key of Life’ album. From the age of 13 to 16, I might have played 500 gigs.”

For good measure, Marsalis was only 14 when he first performed as a trumpet soloist with the New Orleans Philharmonic.

He chuckled when asked if his school work was adversely impacted by his constant funk gigs in the Big Easy.

“No. I brought my homework with me,” said Marsalis, whose family-friendly Wednesday concert at the Balboa Theater with his Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra features the San Diego debut of “Spaces” (about which more in a moment).

“People would be laughing at me, because I’d be doing my homework on the gig! I was the youngest person on that scene. I was probably 13, and the average age of people in those bands was between 20 and 25. We had a great time. We competed in a lot of ‘battle of the bands.’ To this day, I can remember the names of the bands we lost to.”

Bobby McFerrin (left) and Wynton Marsalis joke around backstage at the 1983 San Diego Jazz Festival, where they performed on UC San Diego’s Revelle Campus lawn. (Photo by Grace Bell)

Winning ways

Losing has not been a common experience for Marsalis, who was 17 when he moved to New York to study classical music at Juilliard in 1978. At 18, he joined Art Blakey’s famed Jazz Messengers band. Within a year, he was leading his own group. It featured his brother, saxophonist Branford Marsalis, a veteran of both the Jazz Messengers and the Creators.

In 1984, Marsalis became the first artist in history to win Grammy Awards for jazz and classical recordings in the same year. In 1985, he became the second person to accomplish that joint-Grammy feat. He was all of 23 at the time. No other artist since has won jazz and classical Grammys in the same year.

Marsalis composed his first dance score, “Citi Movement (Griot New York)” for Garth Fagan Dance in 1992. Five years later, he became the first jazz artist to ever win the Pulitzer Prize for music, thanks to his sweeping oratorio about slavery and freedom, “Blood on the Fields.”

His most recent music and dance work, the jazz opera “The Ever Fonky Lowdown,” debuted this year at Jazz at Lincoln Center, which Marsalis co-founded 31 years ago. In 2004, Jazz at Lincoln Center moved into its $128 million New York City headquarters — overlooking Central Park — where it boasts two concert venues, a nightclub, a recording studio and more.

Jazz education programs have been a constant for the nonprofit organization, which in 1995 debuted Essentially Ellington to make Duke Ellington’s music available to high school musicians from coast to coast and support the development of their schools’ music programs.

In 2008, Essentially Ellington expanded to include the music of other top big band arrangers and composers, including Count Basie, Mary Lou Williams and Benny Carter. In 2015, Jazz at Lincoln Center debuted its own record label, Blue Engine Records. The Jazz at Lincoln Center Shanghai nightclub opened in China last year.

“It’s been a struggle, but that’s been the fun of it,” Marsalis said, speaking from his office at Jazz at Lincoln Center. “We have so many people at JALC — all types of people, all ages, from all walks of life. We have volunteers and a very dedicated board. We have a definite philosophy and point of view, which stresses the fundamentals of jazz. …

“We try, as much as possible, to bolster young musicians, but we need to work on it, always. If we had 15 more jazz orchestras across the country, I’d be much happier about the prospects for our students. But we have SF Jazz, Jazz Houston, Jazz St. Louis and the Dr. Phillips Center Jazz Orchestra in Orlando. So we have places doing things that are cause for hope.”

Marsalis happily recounted receiving a recording on his phone earlier that day — “at 4:19 a.m.” — from Vincent Gardner, the artistic director of Jazz Houston. It was sent from Australia, where Gardner was overseeing an Essentially Ellington program, and featured a rip-roaring bebop solo by a 13-year-old jazz virtuoso.

“Vincent sent this tape to all the members of the JALC Orchestra. My phone has been ringing all day with calls from the cats in my band. They’re all saying: ‘Damn! How old is this kid?’ So we have younger people who want to play this music.”

Via long distance, Marsalis marveled aloud as he played part of the recording to his interviewer in San Diego.

“What makes somebody who is 13 want to learn the most difficult aspects of our music, in Australia?” he mused. “And I realize that it’s the difficulty and the challenge of it. When you get older, the pressure to be less than you are (artistically) becomes greater and puts you in a difficult position. Some are willing to make the sacrifice, some are not, and there’s no shame in either.”

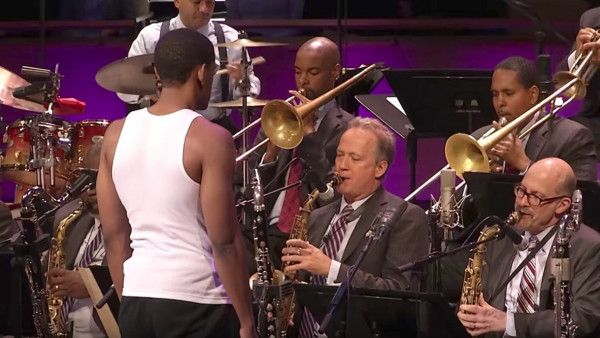

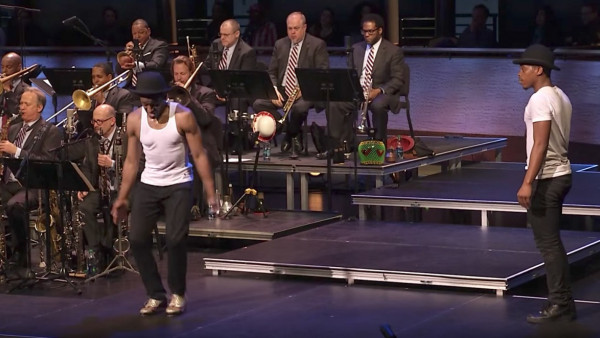

Jared Grimes dances with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, whose leader, trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, is pictured fourth from left in the top row behind Grimes. (Photo by Lawrence Sumulong)

From New Orleans to Harvard

In 2011, Marsalis did a “Music as Metaphor” lecture/performance at Harvard. He was joined by his quintet and former San Diego violin master Mark O’Connor, whose music has accompanied performances by Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and the New York City Ballet.

Dancing is, of course, a tradition that is an intrinsic part of culture and everyday life in New Orleans, where second-line dances are performed at parades and funerals alike.

Derived from the city’s famous jazz funerals, which start as solemn processions and conclude as lively celebrations, second-lining often finds participants strutting in the streets. Accented by twirling parasols or white handkerchiefs, second lining is an all-ages affair.

For Marsalis, though, the first lure of dancing as a kid was that it wasn’t for kids.

“In New Orleans, everybody was dancing,” Marsalis recalled. “My family was living for a while in (nearby) Hanson City, which is really country, if you can imagine it in the 1960s in the segregated South. There was a restaurant/bar that kids were not supposed to go into when they were having dances. Somehow, I stumbled in there and it was men and women, snapping their fingers to Motown and Sam & Dave records.

“I remember thinking: ‘Damn, this must be a lot of fun!’ I knew I wasn’t supposed to be in there, but I lingered in a corner for a while. That was my first understanding of dance that wasn’t second-lining.”

With “Spaces,” the second of three major dance works he has composed to date, Marsalis cites his inner-child as a key inspiration for his “animal ballet” suite, which — in concert — features tap dance dynamo Jared Grimes and Memphis “jook dance” sensation Lil Buck.

Each of the 10 movements in “Spaces” corresponds to a different animal. The musical menagerie included lions, frogs, chickens, and — in the case of the suitably buzzing bees movement — insects.

“I was thinking about, like, an animal dance and the different things that animals do,” Marsalis explained. “I wanted to have one half of the suite that just had the sound of the animals, which were not connected to jazz, but just to sound. Many techniques in European classical music, after the 1920s, used soundscapes. I loved the way composers like (György) Ligeti would use sound as music, so I wanted to do that for first half. Then we go into swing and the jazz equivalent of these animals.

“We equate animals with sounds and rhythms, like swallows, how they go up and down and fly. We can do that in the music. Lions, with their power and roaring, elephants, with that big trumpeting sound they make. Snakes slithering, monkeys chattering; we found interesting spaces to get into.”

Why no duckbill platypus movement?

Marsalis laughed.

“I just picked the ones I liked,” he said. “I didn’t pick a koala, which was my favorite animal growing up. I just picked the ones I thought would lend themselves best to music. I try to be like a child when I write these pieces and write with the wonderment of a child.”

The suite’s “Bees Bees Bees” movement finds Jazz at Lincoln Center’s brass and wind players switching to kazoos. Marsalis laughed again when asked how long it had been, prior to debuting “Spaces,” since he last played a kazoo.

“It had been a while,” he admitted.

“One time I made the mistake of of doing a ‘Young Persons’ lecture and concert where we handed out kazoos to 800 kids, and then I tried to teach the class. Man! Those damn kazoos were going off constantly — Wah! Wah! Wah!”

by George Varga

Source: San Diego Union Tribune