Wynton Marsalis, Young Lion of Jazz

A year ago, even if people hadn’t heard the prodigious trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, they’d probably heard of him. Then, on last year’s Grammy awards, when Marsalis became the first instrumentalist to win “best soloist” awards in both jazz and classical categories, they also heard from him.

No close-mouthed Thelonious Monk, the handsome and articulate Marsalis, 23, surprised the staid audience with an impassioned and, some felt, impolitic acceptance speech, dedicating his jazz award to Monk, Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong and other jazz innovators “who gave an art form to the American people that cannot be limited by enforced trends or bad taste.”

“I say what I think,” Marsalis says now. “Some people said ‘yeah,’ and some people said I was cutting Miles [Davis] and Herbie [Hancock] down. I wasn’t cutting nobody down. Herbie came up to me and said, ‘Man, you were right on time with that.’ “

Marsalis, who is appearing with his quintet at Blues Alley through Monday, seems to be right on time with a number of things.

His debut album in 1982 was also nominated for a Grammy and last year’s two follow-ups set a standard he’ll be pressed to match.

His jazz album, Think of One, has spent 16 months in the jazz charts, including two months at No. 1.

His classical debut, a set of baroque trumpet concertos, spent six months at the top of the classical charts.

He won Down Beat magazine’s trumpet and jazzman of the year honors in both 1982 and 1983, and dozens of other awards, citations and honors.

In the process, he’s helped generate a whole new audience for jazz without compromising his standards.

This is particularly impressive when you consider that five years ago, Marsalis was an on-call pit musician in the Broadway show “Sweeney Todd.” Of course, he was also a prize student at Juilliard, capping classical studies that had begun in New Orleans seven years earlier. Marsalis’ father is a well-known jazz pianist and teacher and his son grew up amid marching, funk and soul bands, large orchestras and small combos. Even as he was studying at Juilliard, Marsalis was playing with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

Despite his successes and youth, Marsalis has had to endure his share of attacks from critics who first saluted his championing of bop-rooted acoustic jazz. While conceding his technical virtuosity and impressive logic, they attack his emotional commitment, his sudden fame and the fact that he has yet to show himself as an innovator, and so what if he’s only 23.

“I get so much publicity, they shouldn’t grant me my youth,” Marsalis says.

Much of the backlash seems directed, too, at Marsalis’ penchant for expensive Italian suits and the fact that he’s not Miles Davis.

But Marsalis, who has openly criticized musicians for what he considers selling out, refuses to be drawn into a confrontation with Davis. “That’s a waste of time, man. I do all my talking on the bandstand,” he says. “I lived with the music that he made 30 years ago, up till he stopped playing jazz. How can you compare me to him? Impossible, man. He’s my musical daddy. If I get better, it’ll be because of what he did; he’s not going to get better because of something that I did. That’s a big difference.”

As for charges that his art is derivative, and often nostalgic, Marsalis points out that “when you step out and play the music, you’re playing in relation to all the music that’s ever been played. What the [critics] are doing is right. It’s what I do myself. Who’re they going to compare me to, my little brother Jason?”

“It’s like with Bird [Charlie Parker],” Marsalis adds, warming up to the subject. “Somebody can say, ‘Lester Young played that on a 1937 record.’ Yeah, but that’s Bird playing it!”

Marsalis’ influences can be traced all the way back to Armstrong, but the most obvious ancestors are Fats Navarro, Clifford Brown, Davis, Lee Morgan, Kenny Dorham and Booker Little, the clarion trumpet voices of the ’40s and ’50s. In the ’60s and ’70s, he says, “everybody wanted to sound like they came out of nowhere. Nobody does that, even Einstein. Nobody. It’s impossible. Except maybe for Berlioz, man.”

Not having role models his own age, Marsalis says, is a serious roadblock.

“When you see young musicians immediately above you playing, it makes you play better than having musicians who are a lot older. Then you say, ‘They’re old, they’ve been playing 50 years, I’ve got 50 years to get to that.’ Somebody’s right above you, you say, ‘Damn, listen to that!’ “

The young lions that Marsalis suggests will inspire that emotion in even younger players include Terence Blanchard and Donald Harrison (“my home boys, we went to high school together”), Washingtonian Wallace Roney, Howard University grad Winard Harper, guitarists Kevin Eubanks and Stanley Jordan, flutist Kent Jordan “and of course the cats in my band, [brother] Branford, Kenny Kirkland, Jeff Watts, Charnett Moffit. Charnett’ll be cool when he learns a little more, he’s just 17 now.”

Why this new generation, so suddenly?

“Cats want to play, they want to use their minds and play and be musicians,” Marsalis says. In the late ’60s and ’70s, “cats wanted to make money. They started imitating rock musicians because they were jealous of all the money. They’d spent all that time learning how to play and then what? It’s not like they were being revered as cultural heroes, know what I mean? Musicians would come in from England and make millions of dollars playing nursery rhyme-sounding tunes. They saw that happening and they said, hey, I’ll play some nursery rhymes too.”

That’s something, Marsalis promises, that you’ll never hear him do. When he first signed with Columbia, they envisioned him as a pop-funk trumpeter in the Tom Browne mold. “I would never disgrace my instrument like that, man, I have too much respect for trumpet to do that.”

Ironically, his best notices have come from the classical side. “I didn’t get one bad review on my classical tour, can you believe that?” he asks, pointing out that his own opinion of those performances was sometimes harsher. “The classical critics don’t have as much room to cut you down as the jazz critics. The amount of opinion they can inject is not that great; it’s if you play the music correctly. Classical critics by and large know more about the music because it’s more codified.”

Still he seems unaffected by the recent criticism from the jazz community. “That makes it more exciting for me. If everybody says I’m great, that’s boring. I like drama.”

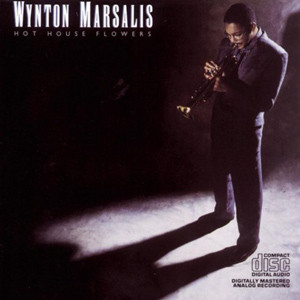

Marsalis’ new album, Hot House Flowers, a collection of standards-with-strings, has provided some drama, mostly the drubbing given to Robert Freedman’s arrangements.

“Nobody can really cut me down enough on this record, so they cut him down,” Marsalis says heatedly. “It’s a ballad album with strings. It’s not what you have in clubs — burning out for a half hour. That’s not what it is.

“People say ‘Wynton, he can’t play ballads, he just plays fast, technical, burnout.’ That’s what the perception is and then they expect everything that I do to be like that. It’s just a different thing. I did that record because I grew up listening to ‘Clifford Brown with Strings.’ When I was a little boy, I listened to that record almost every day, man, for two years, and I said when I grow up, I want to do a record with strings.”

“All I can think about is trying to produce music on as high a level of quality as I can produce. I wasn’t trying to do something that would appeal to people who say, ‘I don’t like jazz, but I like this.’ It’s our responsibility to leave this place better than we found it and try to influence people in positive ways, add to their lives,” Marsalis says, most often through his trumpet.

by Richard Harrington

Source: The Washington Post