Wynton Marsalis’ “Concerto in D” revels in Americana

Wynton Marsalis long ago established his fluency in multiple musical languages, jazz and classical chief among them.

But blues, gospel, spirituals, tango, African chant and other idioms also course through Marsalis’ large works, such as the symphonic-choral “All Rise,” the sanctified “In This House, On This Morning” and the vocal-orchestral epic “Blood on the Fields” (the first jazz composition to win a Pulitzer Prize, in 1997).

Before Tuesday night, however, America never had heard what Marsalis might do with a sprawling, full-throated violin concerto. Yes, he’d proved dexterous in writing for strings in a chamber setting with “A Fiddler’s Tale,” a jazz response to Stravinsky’s “L’Histoire du Soldat” (“The Soldier’s Tale”). But the U.S. premiere of his Concerto in D at the Ravinia Festival, which co-commissioned the work, raised many tantalizing questions.

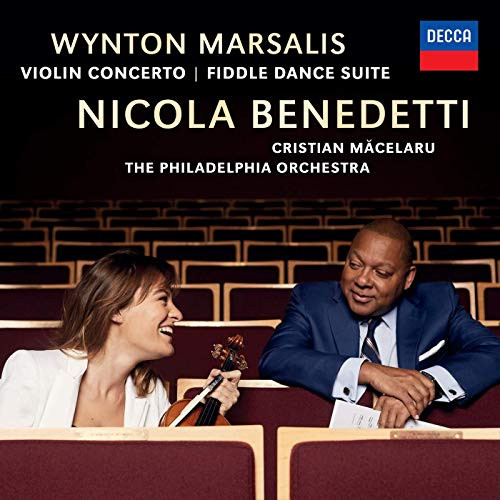

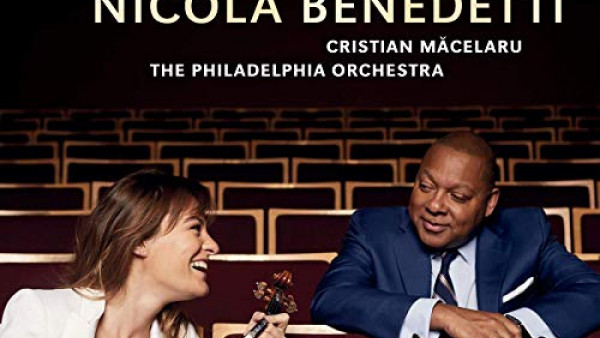

How would his concerto, which he wrote for violin virtuoso Nicola Benedetti, fare alongside landmarks by Beethoven and Brahms, Samuel Barber and Erich Wolfgang Korngold? How would a fiddle concerto penned in the 21st century, and performed at Ravinia by Benedetti with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, deal not only with the legacy of earlier works but with contemporary musical expression?

How would Marsalis’ concerto, in other words, find something new and worthy to say, in light of all that has been penned in a format that stretches back centuries?

Marsalis’ strategy, it turns out, was to take a largely populist approach, endowing the concerto with sweeping melodies, brilliant orchestration, ebullient rhythm and many shades of Americana. Though the concerto did not take on the most profound questions of human existence, as Brahms’ and Beethoven’s masterpieces and some other works of Marsalis’ do, it eloquently directed its attentions elsewhere: toward celebrating American musical vernacular in ultrasophisticated ways.

Its fundamental character was apparent from its first notes, Benedetti — who played the concerto’s world premiere in London last November — unfurling long, luscious lines without accompaniment in the opening “Rhapsody” movement. When the orchestra entered the sonic fabric, under the sensitive direction of conductor Cristian Macelaru, it did so almost imperceptibly, providing a velvety cushion of sound beneath Benedetti’s.

If the intensely lyrical opening pages recalled Ralph Vaughan Williams’ “The Lark Ascending,” it didn’t take long before Marsalis’ score came home to America, evoking Barber’s unabashed neo-romanticism. The jazzy orchestral dissonances underscored the American impulses of the work. In this movement, and others, some of the most probing statements emerged in the cadenza, Benedetti’s sinewy tone and hyper-virtuoso flourishes adding welcome grist to the proceedings.

The “Rondo burlesque” movement that followed provided considerable harmonic and rhythmic tension, its furioso writing for solo violin answered by eruptions from the orchestra. Once again, the weightiest ideas emerged in the expansive cadenza, Benedetti alternating perpetual motion passagework with elastic, majestic phrasemaking. At some junctures, Benedetti’s playing sounded very nearly improvised, thereby telegraphing the jazz undertow of the entire venture.

Even if Marsalis hadn’t titled the third movement “Blues,” its central message would have been clear, and not only from the big, blooming violin theme that launched it. Some sections of this work recalled the slow movement of George Gershwin’s Concerto in F, for piano and orchestra, particularly when Benedetti spun its blues-tinged theme over steady, chordal orchestral accompaniment. This was blues playing and writing of the most refined kind, everything expressed with as much subtlety as delicacy.

The “Hootenanny” finale not surprisingly drew inspiration from certain works of Aaron Copland and Roy Harris, though with more harmonic complexity and with orchestral exuberance born of jazz sensibilities. When the orchestra was going at full tilt, under conductor Macelaru’s adroit direction, its rhythmic swagger bordered on swing, to viscerally exciting effect.

Marsalis’ large works rarely achieve their final form during premiere performances, the composer often reworking a piece for years. In this case, a more exclamatory ending would benefit the entire concerto. For though Marsalis obviously wanted to put the focus on Benedetti in the final pages, the last measures demanded a bigger, more emphatic finish. Or at least a snappier one.

Otherwise, though, there’s no question that Marsalis has created a work of lustrous appeal, its inherent accessibility and vivid colors suggesting that it could well become a repertory piece. It’s not difficult to imagine contemporary violinists taking up the work, though they will be hard-pressed to match the depth and sheen of Benedetti’s tone, the wizardry of her technique, the emotional weight of her rendition of the cadenzas or the naturalness with which she phrased Marsalis’ exquisitely structured lines.

It’s quite possible, too, that subsequent hearings of the piece will reveal its deeper meanings, and that Benedetti’s future performances will enable her to bring them forth. Even now, though, the concerto stands as a significant addition to Marsalis’ oeuvre.

The evening, which inaugurated the CSO’s 80th anniversary residency at Ravinia, closed with music of Ottorino Respighi, conductor Macelaru finding ample poetry in “The Fountains of Rome” and spectacular sound in “The Pines of Rome” (with brass choirs positioned on either side of the pavilion seating for stunning, antiphonal effect).

But the concerto by Marsalis, who joined Benedetti on stage for a final bow, was the main event, its American premiere a distinction for all involved.

by Howard Reich

Source: Chicago Tribune