Wynton Marsalis and Nicola Benedetti: across the divide

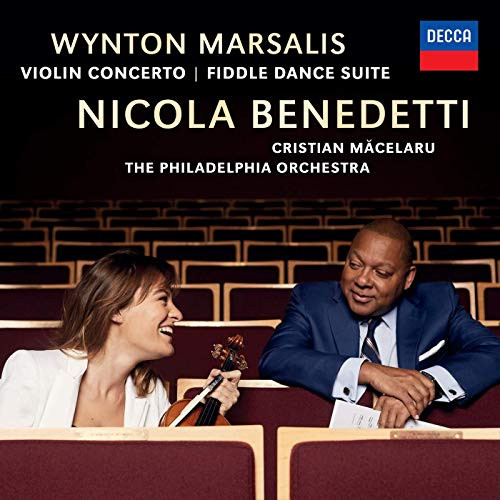

Nicola Benedetti and Wynton Marsalis, photographed in London in August © Carl Bigmore

They might have gone a lifetime without meeting. She is a Scottish violinist, a Yehudi Menuhin School alumna, something of a poster-girl for the British classical music industry. He is a legendary New Orleans-born jazz trumpeter, composer and teacher whose impression of playing an imaginary violin is passable at best. In fact the two musicians happened to meet 10 years ago at New York’s Jazz at Lincoln Center — and in the past few months Nicola Benedetti, 28, and Wynton Marsalis, 53, have become a double act.

That’s because Benedetti is to premiere Marsalis’s first Violin Concerto at London’s Barbican Centre this November. For both it will be the culmination of a long, often painstaking process — which will be revealed in a BBC4 film next year — involving multiple transatlantic flights and phone calls. For Benedetti, it is also likely to be a highly meaningful performance.

“Many people have commented on how well-suited this piece is to me,” she says. That’s not so surprising, because the concerto, which draws inspiration from jazz, blues and Scottish folk music, was written specially for her.

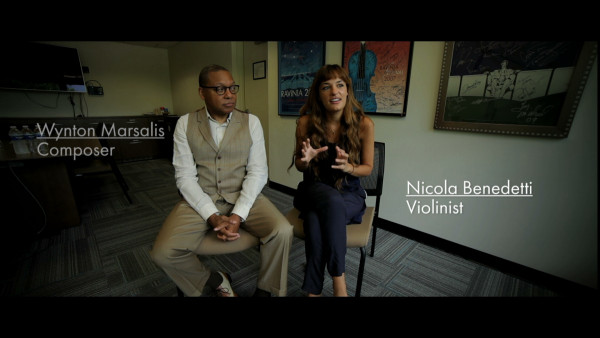

Speaking to them in Leicester Square post-rehearsal, it’s clear that they have certain features in common. Both are passionate about introducing and promoting music to young audiences. Both are warm characters, with a tendency to erupt, mid-sentence, into noisy laughter. And, when it comes to their analysis of this concerto, both are obviously on the same page, even if it’s not always 100 per cent clear what that page is saying.

Both, for example, refer to the work’s rapid “internal dialogue”. When I ask for clarification, Marsalis reaches for an analogy. “Say I’m a boy that you have a crush on,” he says in his distinctive growl, “and you want to give me a Valentine’s gift. The second I take it you wonder whether you should have given it to me. Then you look at me and think, ‘This guy is stupid’. Then I do something sweet, and you think, ‘Yes, I should have given it to him’. You just went through about three progressions in two seconds.” He smiles reassuringly. “That’s what this piece is like.”

How easy, I wonder, is that to convey on the violin? Not very, according to Benedetti, who maintains that the work presents multiple, and consistent, challenges. “There is something that I haven’t got to yet, but that I know this music is going to ask of me: the ability to let go of barriers and inhibitions; to just trust myself and everyone around me to be really bare.”

That very quality is fundamental to jazz, which, as Marsalis reminds me, relies heavily on instinctive reactions. But there is plenty, he insists, that distinguishes this concerto from a piece of jazz, not least the lack of rhythm section and, to Benedetti’s visible relief, the fact that the soloist is not required to improvise.

Many jazz composers, unused to writing out a full score, may find that a daunting prospect. But then, Marsalis is not an ordinary jazz musician, having already produced several symphonic works, among them the “Swing Symphony” and the “Blues Symphony”. The first artist ever to win Grammy awards for classical and jazz records in the same year (both 1983 and 1984), he has loved classical music since his childhood. And the structural rigour of composing comes naturally to him: “With any kind of skill, what’s most important to me is form. It doesn’t matter if it’s shooting a basketball, playing a football game, or writing a piece of music.”

What unfamiliar challenges, then, did this piece pose for him? Not his forays into Scottish folk music, surprisingly; on that topic Marsalis is breezily self-assured, insisting that African-American slave music was born out of Anglo-Celtic music. Where he is less secure, apparently, is in his knowledge of classical orchestration, in particular the capabilities of the violin. Not that he isn’t determined to learn, as Benedetti confirms with a wry smile: “Our endurance wasn’t bad in terms of slow-paced phone calls, going through every note in every bar, with him going, ‘Can we play a G? No. How about a G-sharp? Maybe an A? Perhaps a C?’ ”

When it came to producing ideas, however, he was nothing if not efficient. “If something didn’t work, two seconds later I had another four bars from him,” says Benedetti. She admits that her own working methods are rather more methodical. “He says I should practise a little like [he composes],”she laughs.

Nonetheless, she probably won’t be abandoning familiar habits in a hurry, and that goes for repertoire too. Both she and Marsalis insist that this project is not a symptom of boredom or dissatisfaction with the classical canon. Nor is it part of their mission to popularise classical music. As Marsalis maintains, the genre can stand on its own feet, without the help of cross-pollinations.

“If you don’t know Bach’s music or Wagner’s music or Shostakovich’s music, then it will all seem new in its own right. You don’t need to hear Shostakovich mixed with African drumming for that.”

What largely motivated this collaboration then, he says, was the desire to break out of firmly set moulds. “It’s easy to become a victim of what you’re known for, to believe it and not continue to develop,” he concludes. “You have to go your own way.”

Nicola Benedetti performs Wynton Marsalis’s Violin Concerto at the Barbican, London, on November 6. barbican.org.uk

by: Hannah Nepil

Source: Financial Times