Nicola Benedetti gives premiere of Wynton Marsalis’s Violin Concerto

Curiously – for an orchestra that promoted a 12-concert Violin Festival at the end of last season, but which included no new works for the instrument – the LSO followed its recent UK premiere of John Adams’s Scheherazade.2 with another American composer’s violin piece written for a female soloist (Leila Josefowicz), this time by Wynton Marsalis for Nicola Benedetti. Both are substantial, lengthy and impressive works in four movements.

Just as inspiring was the programme in which Marsalis’s Concerto was placed. All four works were composed in America, but each has an Old World connection. Leonard Bernstein, topping and tailing the concert, gives a nod to Bach and with a final extra jazzy movement to his string-less (save double bass) Prelude, Fugue and Riffs – with clarinettist Chris Richards and pianist Catherine Edwards waiting to join in the shindig – and composed his Chichester Psalms for that named Cathedral (even though he conducted the first performance in New York a fortnight before it was heard in Chichester). Stravinsky – an Old World émigré – used discarded music for the film The Song of Bernadette in his Symphony’s second movement and, of course, Marsalis was composing for a Scottish violinist.

The conductor was James Gaffigan – sporting a beard, so almost unrecognisable from his clean-shaven photos in the programme. In dapper concert dress his coat-tails danced to the rhythm of Bernstein’s opener, and his left foot was almost as animated. Sometimes with baton, other times (the last two movements of the Stravinsky) without, he was in confident control, giving congenial support to Ben Hill in the second movement of Bernstein’s Psalms, the boy’s concentration matched his pure-toned invocation of ‘The Lord is my shepherd’.

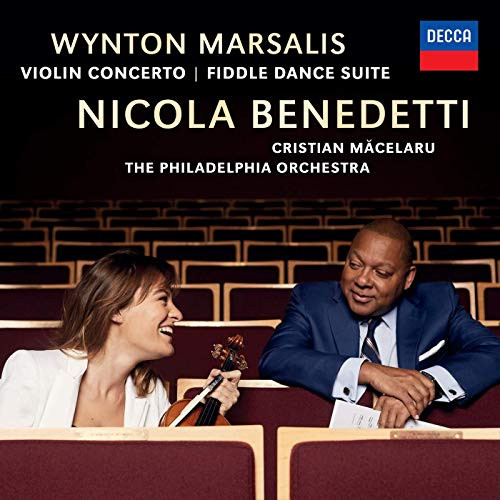

In contrast to Bernstein’s phantasmagoria (brass in the ‘Prelude’, saxophones in the ‘Fugue’ and piano and clarinet leading the ‘Riffs’), Marsalis’s Violin Concerto (in D, as are Beethoven’s, Brahms’s and Tchaikovsky’s, and longer than all of them) starts with a simple lullaby for the soloist, accompanied by harp (Bryn Lewis). The programme note (by Alyn Shipton) was rather confusing in its description of the four movements, particularly in not making any mention of either of the two substantial cadenzas, the second of huge length which – on this one listening – was hard to place (around the end of the second movement or early in the third). Both, but particularly the second, were a tour de force for Benedetti (thankfully her focus was so persuasive that a repeated vocal irritation towards the back of the Stalls intruded only marginally), and essayed various moods and styles, as does the Concerto as a whole.

The general ‘cradle to not-quite-the grave’ trajectory of the work moves from the gentleness of the first movement (‘Rhapsody’) through to a circus visit in the second (‘Rondo Burlesque’ ) and then a church setting (‘Blues’), including a sermon and a wedding, with the Finale (‘Hootenanny’) taking us to the drunken wedding reception, with orchestral foot-stamping and some themes that distinctly reference Benedetti’s national heritage. But after the dancing, in the pale light of a new dawn, the Concerto ends reflectively, Benedetti turning into the orchestra to end on a whisper.

Hugely involving, richly orchestrated and with a wow of a solo part, this trumped Scheherazade.2 for sheer enjoyment and marked a most impressive return to the orchestral platform for Marsalis. Unfortunately he couldn’t be present as he’s on tour with the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra.

After the interval, the somewhat more acerbic Stravinsky cooled the audience down in a direct account of Symphony in Three Movements, almost pugnacious in its sobriety. It was exactly the corrective needed to prepare us for Chichester Psalms, for which the London Symphony Chorus had had a long wait. With the four solo voices in the back row, and Ben Hill at the front, there was a sense of musical layers, which also went antiphonally as Bernstein often uses male and female groups separately. The transliterated Hebrew was largely audible from Simon Halsey’s well-drilled singers. Thus Gaffigan’s snapshot of 20th- and 21st-century ‘American’ music was brought to a memorable close. Afterwards, the foyers were buzzing: job well done from all concerned.

by Nick Breckenfield

Source: Classical Source