Marsalis Shows China That Jazz Isn’t Just a Word

In their first 48 hours of music making here, Wynton Marsalis and his Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra put on two smooth performances before well-dressed audiences, two educational events for Chinese jazz colleagues and schoolchildren, and two smoking jam sessions with local musicians for a small, ravenous circle of fans.

They received uncommonly nice treatment from the Ministry of Culture and had their pictures taken with local music personalities ranging from the rock legend Cui Jian to the People’s Liberation Army Jazz Band.

And all this after a climb up the Great Wall. Today and Wednesday they will be in Guangzhou, their last stop on the China leg of a world tour celebrating Jazz at Lincoln Center in the year 2000.

‘‘I tell you, we made it up to that first tower,’‘ Mr. Marsalis said of the climb. ‘‘That was good. It took a lot of dedication to do that.’‘

It will take a lot of work to open up the small market for jazz in China, where a home-grown jazz album has never been produced and most people know the form only by name. In Beijing, home of China’s only real jazz scene, a few veteran musicians, Chinese and foreign, make their music at several bars and international hotels. It is usually limited to improvising by one of a dozen bands whose members have picked up what they know from smuggled John Coltrane or Louis Armstrong CD’s.

The city was the first stop on a tour loftily intended to expose much of the world’s population to the wonders of jazz. The China part of the tour was sponsored by the Sony Corporation and locally organized by the China National Culture and Art Company. The orchestra goes next to Australia, New Zealand, Taiwan, Japan and Hawaii.

Duke Ellington never got to China, nor did Louis Armstrong, so this trip is a milestone, said Rob Gibson, executive producer and director of Jazz at Lincoln Center.

The orchestra has faced some obstacles. Officials in Shanghai initially refused to let the ensemble play at the Shanghai Center Theater over the weekend because ‘‘they have to think that it’s high art before they let it take the stage,’‘ said Chen Jixin, executive vice president of the local organizing company. Officials relented after the local organizer sent a packet of material documenting the prestigious places Lincoln Center Jazz has played, Ms. Chen said.

Beijing’s arching 700-seat Century Theater was about 90 percent full for the two opening shows, but Ms. Chen indicated that hundreds of tickets had been given to the media and officials. Ticket prices ran from $15 to $95. Permits for the event did not come until Jan. 24, and many white-collar workers had left town for the Chinese New Year by the time promotions were under way.

After Mr. Marsalis and company, dapper in charcoal suits and navy polka-dot ties, enchanted an evening crowd with a potent rendition of Ellington’s ‘‘Chinoiserie,’‘ The Beijing Evening News compared their level of mastery to that of the N.B.A. All Stars or the wulin masters, a reference to a martial arts tradition.

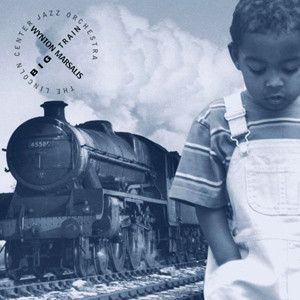

Mr. Marsalis spent a few minutes at each concert explaining the onomatopoeia of his latest album, ‘‘Big Train,’‘ and his remarks seemed to have an effect. Li Zhixin, 35, noted that trains in different places sound very different But ‘‘I knew it was a train when I heard that hoo-hoo,’‘ he said, adding that with Mr. Marsalis’s introduction, ‘‘I think I have a deeper understanding of what he’s doing.’‘

Mr. Marsalis said he had come to China with no preconceived notions of the musical tastes or the level of jazz in China. ‘‘It’s something my daddy always taught me. He said ‘Son, if you don’t know, you don’t know. You got to go to know.’ ‘’

During an educational concert on Wednesday, the orchestra leader had young students stomping their feet in rhythm. To teach them the concept of shifting out of beat, he had them repeat the word syn-co-pa-tion.

Li Xiaopeng, 16, a junior high school student, said he normally listened to Flower, a Chinese pop alternative that is a sensation with teenagers here. . But he said, ‘‘I think Chinese my age should be able to accept this music because it’s pretty vigorous.’‘

Liu Yuan, formerly the saxophonist for Cui Jian and now the only real name in Chinese jazz, said that no amount of new information could make up for the scarcity of bands and clubs. ‘‘We’ve seen what’s happened in Taiwan and Hong Kong,’‘ he said. ‘‘What’s the use of being able to read about it if you can’t go listen to it?’‘

Aspiring jazz musicians face stumbling blocks from the beginning of music school, where there are practically no teachers with jazz backgrounds, said Zhang Longyun, a saxophonist who graduated from the Central Academy of Music and has a day job selling antique furniture.

Mr. Marsalis’s workshop for musicians at the CD Cafe, Beijing’s one established jazz hangout, was packed.

Mr. Liu, who played at the event, said: ‘‘A lot of people thought that he might come down hard on us, but I didn’t find that at all. He was incredibly patient.’‘ The main lesson he took from Mr. Marsalis, he said, was to be forceful.

The concert tour opened with repeated reminders to audiences to turn off videotape recorders and cell phones, which are ubiquitous here. There was the odd jing-a-ling, but Mr. Marsalis was not about to pass judgment. Paraphrasing words uttered by Ellington during a taping of ‘‘Chinoiserie,’‘ he said: ‘‘No one knows who’s in the shadow of whom. Every cliche comes from someone’s perspective.’‘

by Jonathan Ansfield

Source: New York Times