How Wynton Marsalis is like Mozart - and why his concerto in Philly is for violin, not trumpet

Supposedly running 50 minutes at its 2015 London premiere, the concerto would seem to be one of the longest pieces of its kind. Now that it’s arriving for Philadelphia Orchestra concerts Thursday through Saturday at the Kimmel Center, the piece has a more Brahmsian length of 40 minutes. Rest assured, though, this concerto doesn’t sound like Brahms.

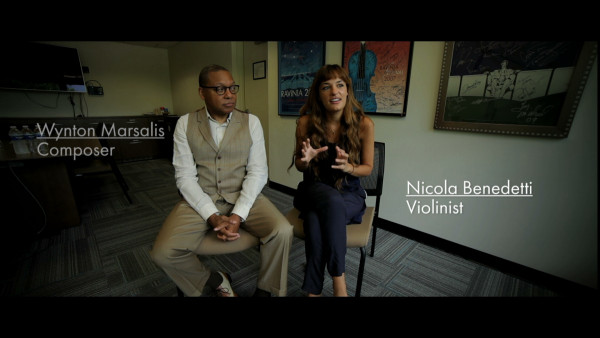

“It’s always about finding the sound of something vernacular. I love our music. I don’t feel like I need to imitate German composers at all,” said the 56-year-old Marsalis, the multi-Grammy-winning jazz trumpeter. “I went around for years with Schoenberg’s Theory of Harmony under my arm, but I never felt that was the conclusion of American music.”

That still doesn’t explain how the piece turned into such a whirlwind, or, in the words of Los Angeles music critic Laurie Niles, “a storm that may need more taming.”

Even though Marsalis says he only revised five minutes out of the piece, that’s still a fair amount of concerto real estate. The essence of the piece remains, said celebrated Scottish violinist Nicola Benedetti, who will be the Philadelphia Orchestra’s soloist in her subscription debut. The exception is her cadenzas, which had “several pretty major overhauls,” she said in an email. She knows: The piece was written for her.

“I worked with Nicky quite a lot,” said Marsalis. “I love writing for people. I’ll stay up day and night. I love making it better. I love having an advocate like her. … All of the psychological complexity of the work comes from her … whether a spiritual church feel, a blues sensibility, or something based on a dream.”

The New Orleans-born Marsalis is best known for jazz, including his current position as artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center. But he has been writing concert works since the late 1990s, most notably the Pulitzer Prize-winning Blood on the Fields.

The Violin Concerto is a series of dramatically different episodes. One movement is subtitled “Rondo burlesque” (a term Mahler used), and another is dubbed “Hootenanny.” They demanded more detailed musical information than he thought. In one phrase, he asks to “collapse in a sigh, a sigh like somebody who just died.”

Marsalis also resisted ending with a bang. Instead, the piece seems to amble off into the horizon, like some storytelling bard leaving you to think about what you’ve heard.

The whole package, “redefines what American music is in the 21st century … ,” said the orchestra’s conductor-in-residence Cristian Macelaru in an email. “On first hearing, the piece can seem episodic, but the true genius … lies beneath the surface where everything is interconnected and interwoven.”

“Every twist and turn, harmony, rhythm, texture, melody … is all so deeply intrinsic to the rest,” said Benedetti. “Pieces that are instantly so relatable and fun don’t always deepen and develop in your heart and mind the more you study them … but the opposite is true of this piece.”

“A new form, to be sure,” said Macelaru. “Nothing is forced, expectations are built, ideas are fully developed. …”

And at this point, the piece is seasoned enough that there’s a possibility of a commercial recording to be made from the Kimmel Center performances.

Marsalis began writing concert works with the encouragement of the severe German conductor Kurt Masur, New York Philharmonic director from 1991-2002. When they ran into each other at Lincoln Center, Masur appealed to Marsalis’ social conscience: “He understood the line between civilization and barbarism, and we have to always nurture common ground,” said Marsalis.

Anyone with historic perspective realizes that Marsalis is not so much of a departure from composers of centuries past. Mozart, Beethoven, and Chopin, to name a few, were virtuoso improvisers like him. Chopin’s written compositions are said to have been a pale shadow next to his improvisations.

Like Mozart (and many current classical composers), Marsalis has no problem working out his thoughts in his head, particularly during those long automobile drives between gigs. Unlike Chopin, there’s no agony in writing his thoughts down. He does it longhand — without using the popular computer software. “My house is full of notebooks. I compose in my head. I compose in the car. I use piano … which is great for getting work done,” he says. “The hardest thing to figure out is the `bottom’ of the orchestra” — similar to a bass line in jazz.

He’s not the only one. Many classical composers resort to what might be called “Mission Impossible Theme” rhythms. Marsalis’ weakness is vamps — those pithy introductory ideas that can be repeated until you’re ready to go on to something else.

“When I wrote All Rise in 1999 for the New York Philharmonic, John Lewis [founder of the Modern Jazz Quartet] said, ‘Too many vamps,’ ” Marsalis recalls. “It became a joke between us. I saw him a few days before he died [in 2001]. He was very very sick, and when I was walking out of the room he said, ‘Work on your bass motion.’ You can’t write vamps for everything.”

What’s truly missing from his concert output is a trumpet concerto. As one of the best-known trumpeters in the world, how could he not write one? Suddenly a nerve has been hit. “I’m never going to do that,” says Marsalis is a steely tone of voice.

But … but … Mozart wrote many concertos for himself.

Marsalis dug in his heels: “He was Mozart.”

Marsalis and The Planets

The Wynton Marsalis Violin Concerto will be performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra with Gustav Holst’s The Planets Thursday through Saturday at the Kimmel Center, 300 S. Broad St.

by David Patrick Stearns

Source: Philadelphia Inquirer