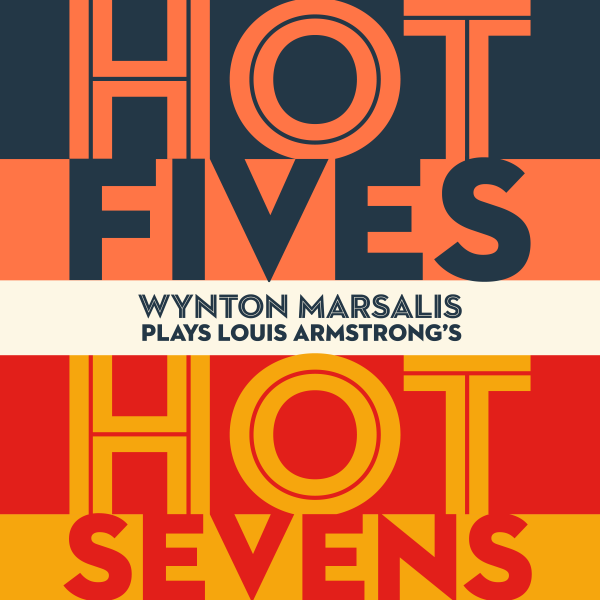

Review: Wynton Marsalis And Louis Armstrong’s Hot Fives, Jazz At Lincoln Center

Arguably the most influential recordings in the history of jazz, Louis Armstrong’s Hot Fives and Hot Sevens were the occasion for three Jazz at Lincoln Center concerts in the Rose Theater, Sept. 28-30, featuring Wynton Marsalis and eight other musicians. As my first visit to New York in several years and my first chance to see the new digs of Jazz at Lincoln Center, I made a point of catching the Saturday night performance which, like the other two, bore the title: “Wynton and Louis Armstrong’s Hot Fives.”

From the outset, I’ll confess that for the greater part of the past 25 years Wynton Marsalis has been a kind of personal cultural hero, occupying a place comparable to T. S. Eliot’s with respect to the traditions of Western literature. Eliot insisted that twentieth-century poetry must reclaim its authentic tradition, which in his view was not to be found in the self-indulgent, romantic excesses of 19th-century poetry but in the 16th-century “metaphysical” poets who achieved an organic unity of style and substance, of emotion and intellect. Moreover, tradition, Eliot insisted, must not be thought of something that is “past”; rather it is concurrent with the present, insuring that “new” poetic forms are grounded in a legacy that is inexhaustibly rich and alive, resonating with all the luminous texts that have preceded it.

Marsalis talks much the same game as Eliot, the main exception being the foreshortening of the traditions and movements which preoccupy him. For 19th-century romanticism, substitute 1970s fusion music; for John Donne and the metaphysical poets, substitute Louis Armstrong and the emerging African-American artist-innovators of the 1920s. In retrospect, Eliot’s influence can be seen in the institutionalization of literary studies and the huge academic enterprise that grew around them; Marsalis’s effect can be seen in the grant moneys he attracts along with the powerful institution for which he serves as artistic director.

For many of us, the Marsalis factor was felt long before his more recent prestigious appointments. Whereas in the ’70s it was fairly common to hear musicians, sometimes including music educators, dismiss Louis Armstrong as an “entertainer” and Duke Ellington’s as a “sloppy” aggregation compared to the machine-like precision of other big bands, such glib pronouncements along with the ignorant attitudes they betrayed quickly fell out of favor in the post-Wynton days of the ’80s. No matter that the jazz heritage had an equally eloquent spokesperson and dominating musical performer in Dr. Billy Taylor; he lacked the boundless energy, youthful persona, and irresistible charisma of Marsalis, whose introduction of the language of the streets to the halls of academe practically forged—and created a whole new audience for—a level of discourse as hip and winsome as it was cerebral and reactionary.

But now that Marsalis has brought unprecedented visibility and profitability to the art, what is the fallout? Practically paraphrasing Eliot, Armstrong’s heir-apparent proclaimed at the top of the program, “We don’t believe in any era of music. We play in all eras at one time.” The result of Eliot’s credo was The Wasteland, the notoriously surreal, complex and groundbreaking poem that became the cornerstone of modernism. The music that followed Marsalis’ pronouncement was hardly modern or groundbreaking. In fact, the lively and colorful contributions of individual musicians notwithstanding, the entire performance could not quite free itself from the musty aroma of a museum piece (a feeling that was enforced by the Preservation Hall configuration of the seated members of the ensemble). Neither fish nor fowl, the crowd-pleasing sounds that filled the auditorium Saturday night manifested a higher level of musicianship and far more respect for the authentic tradition than even the best and most well-intentioned “Dixieland” bands. But the guest of honor and grand patriarch of that tradition, the mother lode himself—namely, Louis Armstrong—was mostly conspicuous by his absence.

by Samuel Chell

Source: All About Jazz