10 Questions to Wynton Marsalis by Sinfini Music

When (and why) did you first write music?

I started writing pieces when I was 13, at high school in New Orleans. In theory class, the teacher asked us if we could compose in the style of the music that we were listening to. I started to compose works in Baroque style and he said: ‘This sounds like it’s in the right style, but it’s not following these rules!’ I remember what my compositions looked like on the paper, but I didn’t take them seriously – they were just for class. Back then I equated being a composer with writing classical compositions that people didn’t really listen to, so I dismissed the idea.

I loved Baroque music back then and I played it a lot – but being from New Orleans, I played a lot of music, you know? Funk music, jazz… I didn’t really think about it. My favourite composer was Bach, but I loved Vivaldi, Handel, all the people who wrote for the trumpet! We trumpet players all have certain music we love: Mahler, Wagner, Shostakovich… Thomas Adès, too: he understands about the trumpet.

What is your composing method?

I like a lot of noise, a lot of distraction – even when I’m writing music there can’t be enough chaos! It does not affect me at all. My house will be packed with people making noise: they’ll be screaming and acting crazy and I can sit at the piano and get in a space with my music and it has absolutely no effect on me. I like the distraction, because it forces me to concentrate even more. When you get into it, you meditate on it.

When I go to write a piece, I set out the form first: I have a very elaborate outline that will cover everything that I’m going to try to do. Then I come up with the themes. I generally get ideas in the morning, but the themes come to me at night a lot of the time. I’m very natural in my process – whatever comes to me, I write it down. I have a strange kind of concept about composing: I think that when you first think of a piece, it’s in that moment that you conceive it. All of it is actually in your mind, and it’s a matter of drawing it out. So I try to focus and concentrate on what I heard when I first conceived the piece.

I write everything out longhand. My method is very strange – it’s not conventional at all, but I’ve been doing it this way for years. I’ll identify the instruments by name, then write it all out on two or three staffs so I can see it all a certain way. I definitely wouldn’t pass a composition class with it! It takes longer, but it allows me to concentrate on what I’m doing.

Which non-musical influences are important to your music?

Everything I’m interested in is to do with form, and how things unfold in time. I love the Oresteia [tragedies] and how they let the Ancient Greeks speak to us across generations. I try not to think in time spans of 50 or 60 years – I try to think in like, 400 years from now. How can I project my form in that ‘macro’ way? I generally love people who have come up with really lyrical solutions to questions of their time, whose work is always avant-garde because of the fundamental way that they approached the problems of human life and of art.

I’m very inspired by many arts and many different types of artists. I love the fundamentals of human beings, their ideas and thoughts. I love art, everything from Mondrian to Matisse. I love the Irish poet William Butler Yeats. I love great films – Elia Kazan, John Ford films. I love photography, and I love all types of literature: Thomas Mann, William Faulkner… I love history. And I love sports, too. My kids always call me ‘the armchair coach’ because I try to predict the way the game is going to go as it happens.

Do you find inspiration in the work of other composers?

I like the worlds of music that are contained in the music of Jelly Roll Morton. He knew such a diversity of people and music. His Library of Congress recordings? It’s unbelievable that a person could sit down and play that much diverse music from memory at that stage in his life, which was not too long before he died. He could play everything from whore house songs to John Philip Sousa marches, from opera arias to original jazz compositions. He displayed an unbelievable level of virtuosity.

For me, Duke Ellington was just the most significant composer of the 20th century. He was a poet, a genius with form – he understood how to negotiate forms economically and was especially a master of short forms. But he also invented a concept of how to develop long form over chorus form – he was the only one who really did it.

From the 20th century I also love Bartók, Stravinsky, Shostakovich – and Ravel, for his orchestration. And then, of the ‘traditional’ composers, I love Bach, Beethoven, Wagner for their mastery.

What do you say when people ask you to describe your music?

Asking me to describe my own music is like asking me to describe myself! You can’t get enough distance from yourself to describe yourself. I can’t do it.

Do you think about your listener when you’re composing?

I’m always thinking about the listener. When you play for an audience, it’s for many people: everybody likes and feels something different, but you’re definitely creating an effect, communicating with them and taking them to different places. So I’m very much focused on the listener: what will move them, and what I can do to do that.

I don’t assume to know what listeners will like, so I have to use my own taste and judgement to determine what people might like. It’s a balance, you know? If you don’t have any of your own objectives, why should you write a piece? But on the other hand, if your objectives are only your own, why should anybody listen to it? It’s about finding common objectives that the listener already cares about – and through them, showing them some of yours. It’s like a conversation.

What’s your musical guilty pleasure?

Music is my life – I deal with it very seriously, and there’s no music that I listen to that I could say is a guilty pleasure! If something doesn’t appeal to me, then I don’t really want to listen to it. Duke Ellington always said that ‘some things are beyond category’ – which I love as a concept but, y’know, we’re not given to understand all languages, we’re not given to understand all categories. But the language of the human soul is universal.

What’s your ideal night out?

For me, it’s just going to some kind of beautiful concert. In New York there’s always great music – it could be a great symphony orchestra, a great jazz band, great South Indian music, or some kind of music that has a dance element in it. When people are playing and dancing it’s good – I like that environment, coming from New Orleans. Some of my friends are very very colourful – they make a lot of noise, and some of them like to imbibe spirits. I like for people to be colourful and have a good time.

And then a late night jam session somewhere, with musicians playing until two or three in the morning. I always love being in a club, late at night, when musicians sit just with the heat of the swing that they’re playing. I wouldn’t need to be playing myself – I love to play, but I also love hearing younger musicians, and if they’re playing alongisde older ones, then I love that even more! I always like to cross generations – it’s an integration of people that has an equality to it.

Contemporary music can be quite daunting for newcomers. What piece(s) would you recommend as a way to start exploring?

I like Thomas Adès – his music is good, colourfully orchestrated. And I like Arvo Pärt too, because his music has a kind of organum sound. It’s a sound that’s so deep in the human consciousness, people can enjoy it. I like John Adams’s music – again, I think it’s great orchestration, and I think that Ellen Taaffe Zwilich is writing interesting music too.

Then there’s Unsuk Chin – her music has sparkles and bursts! And Mark Anthony Turnage: I always loved him. We’re kind of the same age and I’ve watched his career for a long time. Then there’s a composer who has just passed away, Dutilleux. I think his music is very interesting – maybe it will get more recognition now.

I think these composers all know how to deal with the drama of music, and know how to use the orchestra as an instrument in an interesting way. I grew up in an environment where no-one liked classical music, so I was always trying to turn them on to it. I was always drawn to more colourful pieces, especially when they were played live by an orchestra. This experience can be an initial gateway to the music – sometimes much more than the music itself.

Which of your own works would you suggest people listen to as an introduction to your music?

Of all my pieces, All Rise is the one that is most like my philosophy. I don’t know what it is, but I do know that it took more out of me than my other pieces. I was hearing a certain way during that piece: when I got near the end of it, my ears were actually hot. I couldn’t even touch them. The music was coming to me on a stream that I was just tuned into.

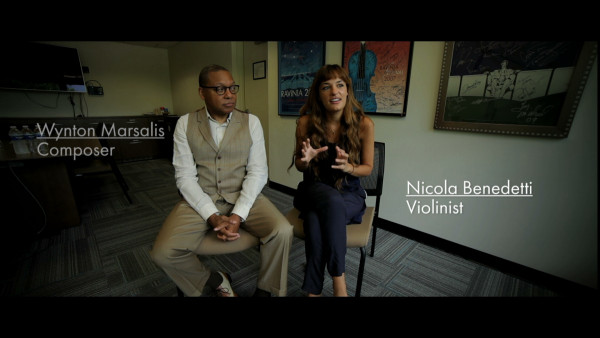

Writing my violin concerto was a lot more work than I thought it would be, but Nicky [Benedetti, the violinist) taught me so much. I enjoyed it! This is a breakthrough piece for me in terms of how detailed I was with the score. In jazz, we don’t have that many instructions on our scores, but with an orchestral score there’s so much editing. A lot of the work was constantly going through my intentions, constantly making sure every sforzando was right and every note was checked.

It took about three months to write – but that was working around the clock while I was on tour. I was playing gigs every night then working on it in the car afterwards. It’s not for the faint of heart!

Wynton Marsalis’s new violin concerto will receive its world premiere on 6 November 2015 at the Barbican Centre, London, performed by soloist Nicola Benedetti and the London Symphony Orchestra under James Gaffigan.

Source: Sinfini Music