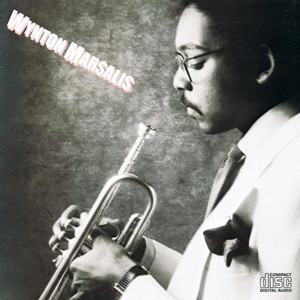

Wynton Marsalis

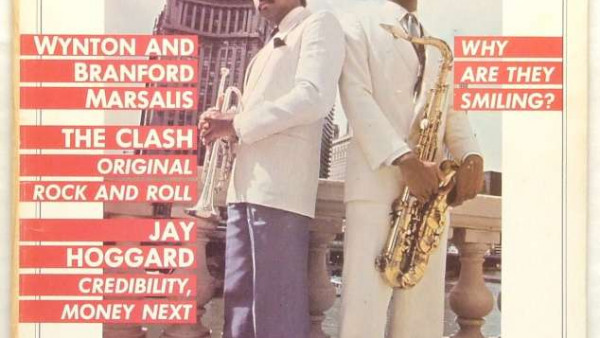

Wynton’s first recording as a leader, made when he was only 19, helped trigger a worldwide renaissance of interest in jazz when it burst on the scene, overflowing with improvisational and compositional energy. Fittingly, Wynton plays here both with Miles Davis’s legendary mid-1960s rhythm section — pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Tony Williams, and with his fellow “Young Lions” — saxophonist Branford Marsalis, pianist Kenny Kirkland, and drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts.

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Quintet |

|---|---|

| Release Date | January 8th, 1982 |

| Record Label | CBS |

| Catalogue Number | KC 37574 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download, LP |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Father Time – (Wynton Marsalis) | 8:12 | Play |

| I’ll Be There When The Time Is Right! – (Herbie Hancock) | 2:35 | Play |

| RJ – (Ron Carter) | 3:51 | Play |

| Hesitation – (Wynton Marsalis) | 5:39 | Play |

| Sister Cheryl – (Tony Williams) | 7:23 | Play |

| Who Can I Turn To (When Nobody Needs Me)? – (L. Bricusse - A. Newley) | 4:39 | Play |

| Twilight – (Wynton Marsalis) | 8:42 | Play |

Liner Notes

Because he is only nineteen years old, trumpeter Wynton Marsalis is one of the most remarkable young musicians to appear in jazz since the early 1960s. His arrival, and what it signals, is especially important because there has been – as there always is – talk about the decline of jazz, and more than a few have sworn they’ve seen the art gurgling on its deathbed. The talk usually continues that all of the younger musicians are being lost to one pop fad or another, that the old hallmarks of discipline and adventure have been replaced by the slick and the predictable, and finally, that most younger players have neither a sense of history nor a respect for the accomplishments of their predecessors. But Wynton Marsalis is a perfect retort to those misconceptions because he has everything – virtuoso technique, passion, intellect, curiosity, a sense of history, and enough humility behind the sometimes comic posture of his sidewalk swagger to guarantee that he will continue to work hard and self-critically at his craft.

Like Jelly Roll Morton, Sidney Bechet, and Louis Armstrong – the structural and linear seers of jazz – Wynton Marsalis is from New Orleans. His father is Ellis Marsalis, a widely respected jazz pianist, composer, and educator, whose admirers are as diverse as Dizzy Gillespie, Hale Smith, and Ed Blackwell. In his home town, young Marsalis got a lot of quality experience in marching bands, jazz bands, funk bands, and orchestras that played European music. He had been given his first trumpet when he was six years old by Al Hirt, but says he didn’t begin taking the instrument seriously until he was twelve. At fourteen, Marsalis won a citywide competition which led to his performing the Haydn Trumpet Concerto with the New Orleans Philharmonic and the Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major with the same orchestra two years later. Throughout high school he played first trumpet in the New Orleans Civic Orchestra, and his prowess got him into the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood in the summer of his seventeenth year. Ordinarily, one had to be eighteen to enter the program, but Marsalis so impressed the staff (which included the notable Gunther Schuller) that he was allowed in and received a citation at the climax – the Harvey Shapiro Award for Outstanding Brass Player.

“I studied classical music,” he says, “because so many black musicians were scared of this big monster on the other side of the mountain called classical music. I wanted to know what it was that scared everyone. I went into it and found out it wasn’t anything but some more music. As far as both musics are concerned, I think – I know – it’s harder to be a good jazz musician at an early age than a classical one. In jazz, to be good means to be an individual, which you don’t necessarily have to be in classical music performance. But because I’ve played with orchestras and all that, some people think I’m a classical musician who plays jazz. They have it backwards: I’m a jazz musician who can play classical music. I always wanted to play jazz. Besides, if you love the trumpet, you have to love jazz because jazz musicians have done the most with the instrument. They have given it the most depth and the widest range of expression. I’m not saying that classical trumpet players aren’t expressive artists. That would be dumb. What I’m saying is that jazz musicians have given the most to the trumpet’s vocabulary in this century. What I’m trying to do is come up to the standards all of these trumpet giants have set – Armstrong, Gillespie, Navarro, Brown, Miles, Freddie Hubbard, and Don Cherry. And that’s not an easy job.”

Marsalis has clearly been making the appropriate moves at this point in his career to get the range of intellectual and performing experience his ambitions demand. At eighteen, he began attending Julliard, worked in the pit band of Sweeney Todd and also performed with the Brooklyn Philharmonia. That summer, he joined Art Blakey and the Jazz messengers. The great drummer had heard Marsalis in New Orleans a few years before and had a place for yet another vastly gifted trumpet player in a group that has featured Clifford Brown, Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, and Woody Shaw. The young trumpeter immediately turned up as a topic of conversation among even the most seasoned and demanding musicians. Certain people started seeing in his work an indication of a fresh development in a music plagued and battered by fusion for the last few years – a growing body of young, serious jazzmen. Marsalis himself reports that he knows of more and more youthful players who are committed to become first-class jazz artists. His own abilities resulted in a contract with CBS Records and a leave of absence from the Messengers in the summer of 1981. Again the young man found himself in extremely swift company – Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams, all of whom appear on this recording. The quartet performed in America, Europe, and Japan. The concert at the Kool Jazz Festival made it clear that there was a new, searching, and powerful voice on the trumpet.

The observations Marsalis makes about the trumpet in jazz describe quite well what makes this recording so listenable. “Some people set new standards in technique and conception, and some set standards in sound and conception instead of virtuoso technique. For some, sound and conception was their technique. But the great thing about it all is that it provided for so much quality. That’s what I want in my music – quality. Technique comes from practice and discipline, but quality comes from understanding. That’s what I want my music to have: The quality of understanding and individuality that makes jazz so great. It’s a long-term challenge.”

It is the level of musical comprehension that makes this such a fine first outing. Marsalis is aware of the importance of variety in his material, of rhythmic, harmonic, and tempo manipulation for tension and release in the compositions, and most importantly, he is approaching his work from a strong ensemble conception. These selections all sound as if the group decisions are as important as the individual ones. The attention to detail and contrast, to subtlety and drama, and the concern for thematic comprehensiveness is quite beyond a group of guys getting together and recording a variety of familiarly musical routines.

The selection of his older brother, Branford (older by one year), as the saxophonist is far from sentimental, for the musical continuity he brings to the material is surprising. Where many players merely wait through the solos of their fellow performers, then run the material they’ve practiced, the Marsalis brothers make conscious use of each other’s improvised ideas and achieve superb wholeness in pieces like the leader’s Father Time. Each player improvises on the melodic motives of the work, superbly counterpoints the other in the lyrical waltz section, is equally effected in his phrasing by Jeff Watt’s rim shots during the Afro-Latin sections. If you have any doubts, listen to the commonality of thematic ideas where the music shifts into straight 4/4. (Clarence Seay brilliantly sets up the tempo 10 bars earlier during Wynton’s feature.) The same is true of Twilight, another of the leader’s pieces. Their inventive dialogue on the trumpeter’s examination of Hesitation (a variation on chord changes from I Got Rhythm) sometimes provides extended melodic ideas that transcend the individual player.

It is also very enjoyable to hear pacesetters like Hancock, Carter and Williams play with such taste and fire on the bassist’s ingenious RJ, such honed lyricism on Who Can I Turn To, and such a doleful groove on Sister Cheryl. Kenny Kirkland once again proves that he is an extremely sensitive accompanist who gives great attention to thematic, harmonic, and rhythmic motives, yet another example of the professionalism and artistry Marsalis sought in his players. Both Seay and Charles Fambrough show that they are swinging bassists capable of swift, complete ideas such as the ones Seay provides throughout Father Time, and the bursts of melodic counterpoint. Fambrough throws in the faces of the brothers and Kirkland during Twilight. Jeff Watts is an intelligent and colorful drummer, and the ways in which he can move back and forth between Afro-waltz meters and straight 4/4 while maintaining a continuity of tempo and conception is quite impressive, as is his providing another tempo alternative for the trumpeter during Twilight – a tempo that is the same one that the entire rhythm section moves into when the saxophonist enters.

For all the discernible influences in these young men it is quite obvious that the record lives up to the leader’s credo, a fitting quote to end these notes: “I want to get the public to understand the real significance and beauty of the music, not by watering it down but by getting to such a place in my art that it will be obvious to all who listen that I’m coming from a great tradition.” Oh, yes, it is very obvious.

–Stanley Crouch

Credits

1. Father Time**

(Wynton Marsalis)

Saxophone: Branford Marsalis

Drums: Jeff Watts

Bass: Clarence Seay

Piano: Kenny Kirkland

Trumpet Wynton Marsalis

2. I’ll Be There When The Time Is Right**

(Herbie Hancock)

Saxophone: Branford Marsalis

Drums: Jeff Watts

Bass: Clarence Seay

Piano: Kenny Kirkland

Trumpet Wynton Marsalis

3. RJ*

(Ron Carter)

Saxophone: Branford Marsalis

Drums: Tony Williams

Bass: Ron Carter

Piano: Kenny Kirkland

Trumpet Wynton Marsalis

4. Hesitation*

(Wynton Marsalis)

Saxophone: Branford Marsalis

Drums: Tony Williams

Bass: Ron Carter

Trumpet Wynton Marsalis

5. Sister Cheryl*

(Tony Williams)

Saxophone: Branford Marsalis

Drums: Tony Williams

Bass: Ron Carter

Piano: Herbie Hancock

Trumpet Wynton Marsalis

6. Who Can I Turn To (When Nobody Needs Me)?*

(L. Bricusse – A. Newley)

Drums: Tony Williams

Bass: Ron Carter

Piano: Herbie Hancock

Trumpet Wynton Marsalis

7. Twilight**

(Wynton Marsalis)

Saxophone: Branford Marsalis

Drums: Jeff Watts

Bass: Charles Fambrough

Piano: Kenny Kirkland

Trumpet Wynton Marsalis

Produced by Herbie Hancock

Executive Producer: George Butler

*Recorded in Japan at CBS/Sony Studios, Shinanomachi Roppongi, Tokyo

Engineer: Tomoo Suzuki

2nd Engineers: Tomito, Ohono, S. Watanabe

**Recorded in New York at CBS Recording Studios

Engineer: Tim Geelan

2nd Engineer: Nancy Byers

Mastered at CBS Recording Studios, New York on the CBS DisComputer™ System by Joe Gastwirt

Production Coordinator: Tony Meilandt

Special Thanks to Lee Ethier; Bryan Bell, Rachel McBeth, Dr. George Butler

Design: John Berg

Photography: William Coupon

Personnel

- Branford Marsalis – tenor sax, soprano sax

- Kenny Kirkland – piano

- Charles Fambrough – bass

- Ron Carter – bass

- Jeff “Tain” Watts – drums

- Herbie Hancock – piano

- Clarence Seay – bass

- Tony Williams – drums

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Hesitation - Wynton Marsalis Septet featuring Branford Marsalis

-

Videos

Videos

Wynton Marsalis Quintet at Montreal Jazz Festival 1982

-

News

News

The Story Behind Wynton Marsalis’ Debut Album

-

News

News

Bandstand Democracy - Downbeat December 2008

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis: Reclaiming the Jazz Tradition

-

News

News

Trumpet: Wynton Marsalis

-

News

News

Marsalis keeps jazz, classical apart

-

News

News

A Common Understanding (Wynton and Branford Marsalis interview): Downbeat December 1982