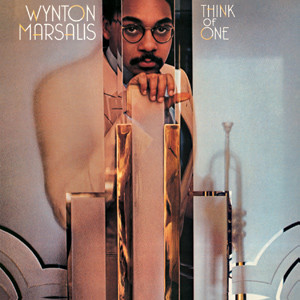

Think of One

Wynton’s second album for Columbia confirmed that he was going to be an enduring presence at the forefront of jazz. In company with Kenny Kirkland on piano, Jeff “Tain” Watts on drums, and his brother Branford on saxophone, Wynton swings hard and joyously on timeless tunes like Duke Ellington’s “Melancholia” and Thelonious Monk’s “Think of One,” and on his own firey classic “Knozz-Moe-King.”

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Quintet |

|---|---|

| Release Date | October 11th, 1983 |

| Record Label | Columbia |

| Catalogue Number | CK 38641 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download, LP |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Knozz-Moe-King | 6:00 | Play |

| Fuchsia | 6:25 | Play |

| My Ideal | 6:17 | Play |

| What Is Happening Here (Now)? | 4:02 | Play |

| Think of One | 5:29 | Play |

| The Bell Ringer | 9:03 | Play |

| Later | 4:08 | Play |

| Melancholia | 2:49 | Play |

Liner Notes

At the age of twenty one, New Orleans jazzman Wynton Marsalis is the crowned prince of the trumpet. But his talent and training are such that he is the enfant terrible of both the jazz and classical worlds, having already impressed Ron Carter as one of the most important jazz players of the last decade and Maurice Andre’ as potentially the greatest interpreter of trumpet concerti in history. His absorption and mastery of the solutions to technical problems personify Hemmingway’s definition of genius – not that he doesn’t practice hard, but that he learns at a superior velocity. Four hours of his practicing might equal twenty – even forty – of another trumpeter’s. There is no other explanation for such virtuosity from a musician who didn’t become serious about his instrument until he was twelve years old. But what is most noteworthy about the young prince is that he knows there are many kinds in the worlds of art, not one of whom is important if his technical expertise fails to musically express human values with singular aesthetic clarity. his goal is to match his technical gifts with a conception comprehensive enough to render the soul and the desire, the will and the frailty, the celebration and the tragedy of human life in the terms of the jazz tradition to which he is most fundamentally attracted. Already, there are impressive tracks on this recording which make it clear that this is Wynton Marsalis’ band, not any other trumpeter’s. Listen to the excellently programmed side one for the authority he brings to pieces that range from a startling interpretation of 4/4 to Latin to blues to ballad. As Duke Ellington said of writer Albert Murray, he is a man whose learning isn’t interfering with his understanding.

It is therefore in keeping with Marsalis, with his New Orleans background, that his grasp of form calls for interludes, breaks, polyphony, dramatic shifts of volume, and tempo changes that are compositional in function and inspire more than strings of solos. Excellent examples are found in his arrangements of “Think Of One,” “The Bell Ringer,” and “Knozz-moe-King.” In the first arrangement, Monk’s piano phrasing is appropriated for five pieces, creating a swing often liberated from a stated meter or tempo. In effect, the listener becomes the rhythm section, both feeling the beat beneath the ensemble and experiencing the release into tempo as though the entire band were executing a complex break that flirted with accent and silence. The contrasting dynamics, the fragmented call-and-response between trumpet, tenor, piano, and bass exhibit the kind of originality most easily perceived when a band interprets material other than its own. With “The Bell Ringer,” Marsalis wanted his original to have a sound larger than that expected of a quintet, so he used all the melody instruments in the voicings, sometimes creating the impression of a second reed through the unusual placements of the tenor. The group achieves colorful surprises when a sustained trumpet note is tonally defined by the combined harmonic motion of tenor and piano as the bass tellingly shifts from vamp to ensemble chords to vamp. Through interludes and drummer Jeff Watt’s vastly different interpretation of the dancing beat for each featured player, suite-like improvisational sections are created rather than solos. The trumpeter’s “Knozz-moe-King” alternates clarion announcements and fleet whiskers in the melody statement and is designed so that the medium tempo in which the tenor improvises supplies a bridge between the jetting velocities of the trumpet and the piano.

Even during the selections that seem more casually designed, Marsalis’ concern with compositional continuity has resulted in coherence that never denies the value of the individual. Over and over, it becomes obvious that each musician consciously uses the intervals, rhythms, and inflections of his fellow players as part of the material on which his own variations are made. And since personnel is part of composition, the band is highly affected by the sequence of improvisers. On the title track, for instance, the piano work is thematically developed by the tenor first, then the trumpet. Conversely, after Branford Marsalis has so craftily reinterpreted the trumpet’s variations on “Later” (even rhyming his concluding rhythms with those of his brother), pianist Kenny Kirkland must bat cleanup, personalizing the contributions of trumpet and tenor.

That conscious sense of continuity doesn’t drain the playing of the passion that gives intellect human substance. If there is any question as to the group’s ability to handle the tradition with the care and arrogance that define individuality, the ferociously sensual joy that animates the aforementioned “Later” will hush that doubt. It is a blues, and the groove that leaps from the turntable is mightily empowered by the lubricating, lard-thick bass beat of Ray Drummond, the billowing and contracting drum assertions of Jeff Watts, and the cunning punctuations of Kirkland, all of whom exhibit the swing of the contemporary rhythm section at its best.

In his playing as well as his writing, Wynton Marsalis has a superior sense of the broadest interpretation of rhythm. He improvises through the lower, middle, and upper ranges of his instrument with a fluid and precise comprehension of how register, interval, and color determined accentual impact: When a listener’s expectations are confounded, surprise will create the illusion of accent. The upshot a growing trumpet style in which all must submit to the mighty god of rhythm, known in jazz as swing. In this respect, perhaps the most profound groundwork for improvising was laid by Armstrong, Young, Parker, and Monk, each of whom personalized and expanded upon the bold ascents and descents that stretched from the Negro spiritual to the percussive bleating, bass-drum emulations of the tailgate trombone. All aspects of music – melody, harmony, phrasing, and timbre – were synthesized for rhythmic impact, regardless of tempo. The trumpeter struts his version of this conception with triumphant joy on “Later,” where he develops his first three improvised phrases, superbly controlling a rhythmic and melodic motif with a thematic and harmonic wholeness extending from Armstrong to Don Cherry. On “The Bell Ringer,” his ideas move with no barriers to execution, and the breadth of clear brass colors gives a subtlety to the lyricism. At one point, a puckish salute to Clark Terry evolves into a sweeping expansion of a triplet motif, at another, the alteration of a smear with a jutting high note echoes Armstrong’s conclusion to his 1938 “Strutting With Some Barbeque”! I am most impressed beyond those performances by his ability to sustain shape and melodic refrains throughout the bravura articulations of “Knozz-moe-King,” and the humble emotional depth with which he delivers Ellington’s “melancholia,” a piece in mood unlike any other in jazz.

Branford Marsalis is an incredibly quick player, a musician capable of responding to the ideas around him with complete musical thoughts. Listen to the way his soprano work on “The Bell Ringer” opens with a motif from the bass and begins to dance atop the extremely original accompaniment of Kirkland’s chords and the imposition of a funk beat by Watts. His ghostly gutbucket sound, the oblique drive of his rhythms, and the thematic skills he asserts in serpentine fashion make him an even more formidable talent on tenor saxophone.

Kenny Kirkland is already one of the best rhythm section players, knowing when and when not to play, how to tighten and loosen rhythms as well as harmonies, and possessing a beat that swings from the first measure. He also has a great ear for piano timbres and gets brilliant combinations of those colors with his melodies, chords, and rhythms. His work on “The Bell Ringer,” “Knozz-moe-King,” and his original, “Fuchsia,” both in rhythm section and features puts him in the front line of young piano players.

It is surprising to hear a drummer in his early twenties who has his own drum tone and knows the secret of providing a different beat for each featured player, but Jeff Watts is such a find. His changes of texture, time, and accent expand and contrast the size of the group’s sound, especially since he uses the rims and the bells of his drums and cymbals as inventively as he does the rest of the set. The way he and Kirkland interplay and superimpose other meters on the basic pulse supplies some of the most exciting moments on this record (e.g. during the piano feature on “Knozz-moe-King”). Phil Bowler and Ray Drummond reveal their respective talents in performances that can easily be distinguished from each other.

In all, Wynton Marsalis has shown considerable growth on this second effort as a leader. His playing is solidifying certain things while extending or eliminating others. But it is of equal importance that he is showing great talent as a leader and that he has had the good fortune to have such a gifted brother as well as a provocative but sensitive rhythm section. No group of young players is more important that these men; they have the true sound of a group. Yes, Wynton Marsalis is very gifted and very lucky, but he is not more lucky than the many who will draw pleasure from his work and the work of the musicians he’s gathered around himself. With players like these, the music’s future is unlimited.

–Stanley Crouch

Credits

1. Knozz-Moe-King

2. Fuchsia

3. My Ideal

4. What Is Happening Here (Now)?

5. Think of One

6. The Bell Ringer

7. Later

8. Melancholia

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet)

Jeff Watts (drums)

Phil Bowler (bass)

Kenny Kirkland (piano)

Branford Marsalis (tenor and soprano saxophone)

Ray Drummond (bass on tracks: 2, 4, 7, 8)

Produced by Wynton Marsalis

Executive producer: Dr. George Butler

Chief Engineer: Tim Geelan

Assistant Engineer: Harry Spiridakis, Mark Cobrin

Recorded and mixed at Mediasound, NYC

Personal management:

Edward C. Arrendell

31 Fort Avenue, Suite 2

Boston, MA 02119

Special thanks: Tom Mowrey for his invaluable assistance, Jack Rovner, Vernon Slaughter, Genevieve Stewart, Debbie Carter, Marilyn Laverty.

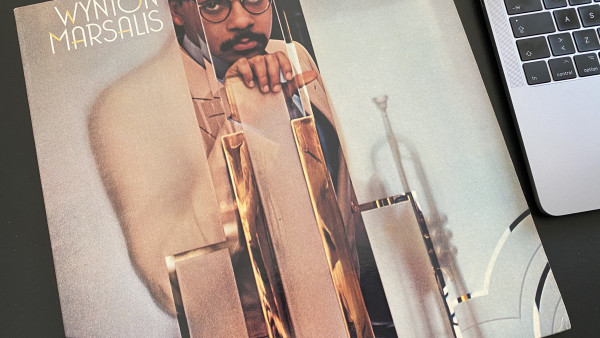

Design: Henrietta Candak

Photography: Art Kane/Photographed at Cafe Seiyoken

Personnel

- Jeff “Tain” Watts – drums

- Phil Bowler – bass

- Kenny Kirkland – piano

- Branford Marsalis – tenor sax, soprano sax

- Ray Drummond – bass

Also of Interest

-

News

News

The Story Behind Wynton Marsalis’ Debut Album

-

Wynton's Blog

Wynton's Blog

Think Of One: I remember that time like it was yesterday, although it was almost 40 years ago

-

News

News

The 10 Best Wynton Marsalis Albums

-

News

News

Explore the life, inspirations and iconic recordings of trumpeter Wynton Marsalis

-

News

News

15 Wynton Marsalis Solo Transcriptions for Trumpet

-

News

News

The Young Lions’ Roar : Wynton Marsalis and the ‘Neoclassical’ Lincoln Center Orchestra

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis: Reclaiming the Jazz Tradition

-

News

News

Marsalis, Jazzy AND Classical