Thick in the South (Soul Gestures In Southern Blue, Vol. 1)

A blues cycle for quintet and sextet that, as Wynton says of the title track to THICK IN THE SOUTH, comprises “a condition, a location, an attitude, a pulchritudinous proposition, and an occurrence,” SOUL GESTURES IN SOUTHERN BLUE ranges through the full glory of the blues tradition. Among other things, it introduces us to the Uptown Ruler, a mythic New Orleans hero whose “persona is obviously multifaceted,” Wynton remarks, because he is “accepted without question in the houses of worship . . . [and] ill repute.” Most of all, the cycle reveals the complex human message of the low moaning blues that echoes in the foghorn of a riverboat, the lament of a spiritual, or the simmering dishes of a home cooked meal. The performers include Marcus Roberts on piano, Bob Hurst or Reginald Veal on bass, Jeff “Tain” Watts or Herlin Riley on drums, Todd Williams and Wes Anderson on saxophones, and Wycliffe Gordon on trombone, with special appearances, on THICK IN THE SOUTH, by two of jazz’s greatest virtuosos, drummer Elvin Jones and tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson.

Album Info

| Ensemble | Wynton Marsalis Quintet |

|---|---|

| Release Date | July 30th, 1991 |

| Record Label | Columbia |

| Catalogue Number | 468659 2 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download, LP |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Harriet Tubman | 7:41 | Play |

| Elveen | 12:13 | Play |

| Thick In The South | 10:14 | Play |

| So This Is Jazz Huh? | 12:27 | Play |

| L.C. On The Cut | 13:29 | Play |

Liner Notes

The first album of the monument that Wynton Marsalis has built in his Blues Cycle is a victorious statement of adventurousness and of the grasp of the soul essentials that have given the blues such international penetration. It is as exciting for the personnel as for the originality with which Marsalis has approached the writing and the arranging. By bringing together unarguable giants such as Elvin Jones and Joe Henderson with the musicians he was then using in his working band, and by writing pieces that expand upon the blues sound as much as they get al the way down into it, the trumpeter and composer has separated himself even further from the limitations of spirit, technique, and conception that musical art is ever at war with, looking for a song to sing up over the barricades.

That singing quality affirms a fact all musicians and listeners should be well aware of: a song will take the soul to school and teach it what it needs to know. The inventive ways that Marsalis uses the five-piece units heard here show how meticulous is his intention to arrive on the lyrical premises of the idiom. A firm sense of the human scope central to this art gives these original works exceptionally inclusive identities. The arrangements balance and contrast the positions of each of the instruments for the expression of a thorough understanding of the call-and-response that leads us all the way back to chattel field hollers and the Negro spirituals that underlie blues crooning. It is also intriguing to hear how Marsalis interprets that crooning’s function within the percussive vision of dialogue, harmony, and form provided by the rhythm section. At the same time, there is the pleasure of experiencing how well each of the pieces is connected for the overall effect structural unity gives to music. As much thought as passion and intuition has been put into this volume of the Blues Cycle, which gives it human fullness.

But, as this writer has observed before, personnel in jazz is part of composition-in-performance. Whatever a piece sounds like when someone plays it done, if it is written for an ensemble, the players who improvise the variations determine the sum of the impact. So the jazz composer picks players for the way they hear melody, harmony, rhythm, color, and form, and for the way they respond to others. Therefore, the selection of Elvin Jones and Joe Henderson as guest masters is, finally, compositional. They supply over 70 years of professional experience between them, and each has consolidated the fundamentals of the history of his instrument.

In the wake of the innovations of Max Roach, Kenny Clark, Roy Haynes, and Art Blakey, Elvin Jones expanded the language of his instrument through an innovative ability to orchestrate percussion in independent components of swing. That gift attracted John Coltrane to him and Jones became the center of a rhythm section built upon the drums. The way in which the Coltrane Quartet approached swing, blues, ballads, and Afro-Hispanic rhythms added much to the possibilities of the art form, making it one of the supreme chamber ensembles of the century. With Coltrane, the once enigmatic aspects of Jones’s style became perfectly clear. He orchestrated the time across the entire set, using the ride cymbal as only one part of his perpetual variations on the phrasing of the meter, the surrounding improvisations, the tension and releases of the form, and the shaping of the rhythm. Jones understood that the trap set is an ensemble of drums and cymbals and played it as one. He also brought virtuoso clarity to every kind of drum equipment. His work with sticks was equalled by his brush playing and his use of mallets. The weight of passion in his beat has never been exceeded, but that heroic emotion is given a large part of its force by the musical logic of his designs.

“Elvin Jones is someone whose work has been in my life from the earliest days of my listening to jazz seriously,” says Marsalis. “There was something about his wing nobody else had. I didn’t know what it was then, when I was first starting to check him out, but I could feel this particular thing in it that was so different from any drumming I had heard. When I moved to New York, I used to go hear him at the Vanguard whenever he was playing, and it became clearer and clearer what he was doing. The first thing you notice is that he is so in control of the drums and cymbals that he is able to play in layers of rhythm. He developed a style that has deepened over the years until he is much, more greater now than he was when he was with Coltrane, which produced some of the best music ever played. But Elvin honored me and all of the rest of us by agreeing to play on two songs with us. He represents everything we are hoping to do in our own careers. There is a deep, deep majesty to Elvin that comes from a very rare combination of great talent, discipline, and sincere humility. That humility is why he continues to develop. He doesn’t take anything for granted. He is one of the greatest men I have ever met.”

As his improvisation on “Elveen” shows, Joe Henderson is a musician’s musician. One of the truly great tenor players who came to recognition in the early sixties, he has developed a style that embraced and absorbed–rather than aped–conceptions of such wide application as those that extend from Charlie Parker through Sonny Rollins, Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane. Before he was 30 years old, Henderson had already recorded classic dates with Kenny Corham, Horace Silver, and Andrew Hill, as well as the marvelously timeless Made For Joe under his own leadership. An inspirationally consistent player, Henderson has so risen in stature among his fellow musicians over the years that whenever he performs to packed houses in New York, the audience will be run through with jazz players of various instruments, all aware that a master in the midst of expression and instruction is at the microphone.

“Joe,” says Marsalis, “is somebody you have to like if you like jazz. I have always loved listening to him, and when I conceived this part of the Blues Cycle, I knew I wanted him. As soon as he pulled out his horn and we heard that sound and all of those harmonic bombs he was dropping–plus that swing–we knew this man was going to give us some thorough musical information and musical feeling. To have him and Elvin on the same session, well, you just have to be grateful for that. I’m also proud of the unit I had in Marcus, Bob, and Tain, all of whom are at the forefronts of their instruments in this generation. I’m very happy to have been able to document this.”

Then there is the playing of the leaders himself. His inventions have the authority of deep blues feeling, something many of us had come to believe we would never hear from musicians born after 1960. But there it is–stark, poignant, full of swing and desire. No matter the complexity of the particular piece of music, Marsalis is always seeking out the elevated power of song given the sort of beauty peculiar to blues. Improvisations such as the ones heard on these pieces make it seem as though Marsalis is perhaps the most commanding trumpet handler of the blues to have arrived in the last three decades. As ever, he is very articulate about what he was after.

“I was thinking about what King Oliver told Louis Armstrong when he was young and wanted to run all over the horn: ‘Boy, you better play some lead on that horn; you better play some melody.’ I was thinking about that and trying to open up my sound and get down to some essences so I could move as far away from sounding like a saxophone as possible. I wanted to play some trumpet out of the line that comes from King Oliver and Louis Armstrong over to people like Sweets Edison and Ray Nance and Doc Cheatham. But I’m not talking about a particular style; I’m talking about an attitude toward the horn itself. Fats Navarro had that attitude; his ambitions were clarion. So were Clifford Brown’s and Booker Little’s and Freddie Hubbard’s. Miles Davis understood it in his jazz period, too. And though people associate Dizzy Gillespie’s style with the saxophone, he is definitely documented dealing with some clarion horn. I’m not against playing fast. It’s just that now I understand fast as only an aspect. If you base your style on a clarion approach and know when to play fast, your music will have more variety and range. That’s why Louis Armstrong had such an impact. He knew how to make the trumpet speak on the most profound level. If we aspire to an understanding of what he gave to music, all of our work will improve.”

In his own words, Marsalis describes each of the pieces:

“Harriet Tubman” makes homage to a woman who acted as a personal agent against the slavery that so severely limited the spiritual potential of our nation and was detrimental to the fulfillment of our democracy. She and the Underground Railroad represent the same thing that the blues does, that optimism at the core of the human will which motivates us to heroic action and tells us: NO MATTER HOW BAD, everything is going to be all right. This blues begins in the bass with a motif that speaks of late night mystery. It’s muted bell-like quality uses bass harmonics for an allusion to the African thumb piano. The drums come in with another meter to further enhance the African underpinnings. Siren horns and a bass vamp signal the beginning of a journey on the Underground Railroad, then the sound of the blues and the wash of swing identify this as a uniquely American expression. The piece ends as it begins, in the bass, reminding us that even though the journey has ended, there is still much more to do, and other trips, no mater how dangerous, will be on schedule, will be in a minor key and departing.

“Elveen” is inspired by the circuitous aspect of Elvin Jones’s rhythmic conception and the motific and harmonic devices employed by Thelonious Monk in compositions such as “Blues Five Spot” and “Raise Four.” The orchestration is based on the contemporary drum set. The melody stated by the trumpet is a repetitive triplet motif which parallels the constant swing of the ride cymbal, while the tenor counter-melody jobs in and out on various subdivisions of the triplet like the punctuations of the snare drum. In the second chorus, the bass plays another counter-melody that also functions as an ostinato and plays against the original counter-melody of the tenor much like the snare and bass drum conversations which have always been fundamental components of jazz drumming since Kenny Clarke.

“Thick in the South” is a condition, a location, an attitude, a pulchritudinous proposition, and an occurrence. It is so southern as to not be from the American South at all, but from somewhere down there, below the geographic and anatomic equator. This Phrygian, then minor blues, celebrates the complex and ever-changing interactions that define contemporary living–the new-fangled technologies, differing cultural agendas, and so on. The metric mysteries and structural shifts attempt to mirror the sometimes perplexing but finally exhilarating experience of surprise and variety when faced with determination and an open heart.

“So This Is Jazz, Huh?” This question is asked by a couple upon arriving at a jazz concert out of curiosity. Perhaps they have heard some pop type of jazz on the radio and come full of expectation. The music starts. It is a blues in a major tonality, a mellow sound using a subtle groove somewhat reminiscent of what might be heard on late night radio. It continues. Alas, it is a blues using many different chords, the language, swing, modulations, and improvisations of actual jazz. They exchange glances that say, “Do we like this?” Then one of them says to the other or they say in unison, “So This Is Jazz, Huh?”

“L.C. On The Cut” is not a portrait but a description of the world traversed by Larry Cherry in his role as psychologist, philosopher, politician, comedian, storyteller, and defender of traditions. In other words: barber. L.C. personifies the feeling of the mythical down-home barbershop, that place of high comedy and seriousness where boys aspire to manhood and men order the chaos of recollection and the moment through spirited discourse. Ever adjustable but always himself, L.C. is much like a jazz musician. he is an individual and a man of the community. Besides, he is literally one who snips, clips, brushes, and straightens out your head.

As both another statement of the disdain Wynton Marsalis has for the idea of the so-called “generation gap” and as part of a public monument raised to honor the range of the blues, Thick In The South is a superb gateway to the entire cycle, Soul Gestures In Southern Blue. It begins with an homage to the swinging chariots that announced the impending arrival of the Underground Railroad and concludes with the good humor, style, and wisdom of the call-and-response that defines the down-home barbershop. A superior event in itself and a superb preparation for the extensions heard on Uptown Ruler and Levee Low Moon.

–Stanley Crouch

Credits

All songs written by Wynton Marsalis

Musicians:

Wynton Marsalis, Trumpet

Marcus Roberts, Piano

Joe Henderson, Tenor Saxophone

Bob Hurst, Bass

Jeff Watts, Drums

Elvin Jones, Drums (“Elveen” “L.C. On The Cut”)

Produced by Steve Epstein

Executive Producer: Dr. George Butler

Chief Engineer: Tim Geelan

BMG Engineer: Dennis Ferrante

Recorded Digitally onto the Sony PCM 3324 Digital Tape Recorder at BMG Studios, New York.

Mixed onto The Sony PCM 1630 2 Track Digital System at Sony Music Studio Operations, New York.

Monitor loudspeaker: B&W 801

Mastered at Europadisk Ltd., New York

Exclusive Personal and Financial Management:

AMG International, P.O.BOX 55398, Washington, DC 20011

Edward C. Arrendell, II/Vernon H. Hammond, III, Partners

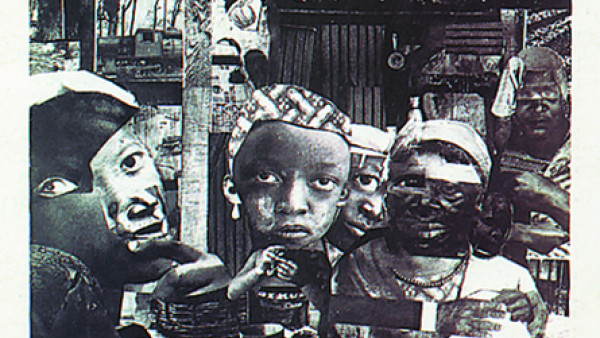

Cover Artwork: Romare Bearden. Mysteries. 1964.

Photomontoge. 28½ x 36¼ inches

Estate of Romare Bearden,

Courtesy ACA Galleries, New York, NY.

Publisher:

Track 1-5: Skaynes Music

Personnel

- Bob Hurst – bass

- Jeff “Tain” Watts – drums

- Elvin Jones – drums

- Joe Henderson – tenor sax

- Marcus Roberts – piano

Also of Interest

-

News

News

A change of key - His Septet behind him, Marsalis takes a new direction

-

News

News

Wynton’s Decade: Creating a Canon

-

News

News

Blues Alley Cat Wynton Marsalis

-

News

News

He trumpets mature jazz

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis Gets Kind Of Blue

-

News

News

NEW RELEASES : Eclectic ‘Blues’ From Wynton Marsalis

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis, Immersed in the Deep Blues

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis: Reclaiming the Jazz Tradition