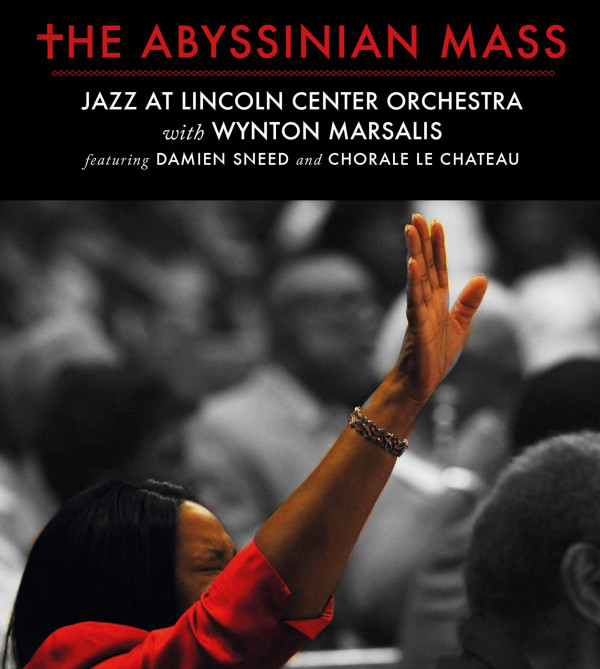

The Abyssinian Mass

In 2008, nine-time GRAMMY® Award winner Wynton Marsalis was commissioned to write a piece commemorating the 200th anniversary of Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church. The result was a sacred celebration: a sweeping composition for a big band and 70-piece gospel choir. In 2013, award-winning recording artist Damien Sneed and his choir, Chorale Le Chateau, joined the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis for a 16-city, 19-concert tour across the South that took the musicians into deep dialogue with the African American tradition. Now, The Abyssinian Mass—Marsalis’s first original recorded composition in six years—documents this piece’s immense power to make audiences clap their hands and sing along to its joyous spirituality, its profound swing, and its bluesy swagger.

This landmark double album also includes a new essay from renowned public intellectual Leon Wieseltier and a bonus DVD documentary that features performances, interviews, and insights into the process behind The Abyssinian Mass.

Album Info

| Ensemble | JLCO with Wynton Marsalis and Chorale Le Chateau |

|---|---|

| Release Date | March 18th, 2016 |

| Recording Date | October 24-25-26, 2013 |

| Record Label | Blue Engine Records |

| Catalogue Number | BE0005 |

| Formats | CD, DVD |

| Genre | Jazz at Lincoln Center Recordings |

| Digital Booklet | Download (pdf, 4 MB) |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| CD 1 | ||

| Devotional | 8:34 | Play |

| Call To Worship | 5:11 | Play |

| The Lord’s Prayer | 4:13 | Play |

| Processional: “We Are On Our Way” | 7:25 | Play |

| Invocation And Chant | 6:29 | Play |

| Responsive Reading, Matthew 5:3-12 The Beatitudes | 7:57 | Play |

| Gloria Patri | 5:05 | Play |

| Prayer: “Pastoral Prayer” | 13:05 | Play |

| Choral Response: “Through Him I’ve Come To See” | 2:21 | Play |

| Anthem: “Glory To God In The Highest” | 7:01 | Play |

| CD 2 | ||

| Scripture: Isaiah 56:7 | 2:36 | Play |

| Meditation: “Lord Have Mercy” | 4:59 | Play |

| Sermon: “The Unifying Power of Prayer” - Part I: “This House Is God’s House” | 4:17 | Play |

| Sermon: “The Unifying Power of Prayer” - Part II: “The Power of Prayer” | 4:57 | Play |

| Sermon: “The Unifying Power of Prayer” - Part III: “Everyone Has a Place” | 3:15 | Play |

| Invitation: “Come and Join The Army” | 4:33 | Play |

| Offertory: The Father | 2:39 | Play |

| Offertory: The Son | 3:22 | Play |

| Offertory: (You Gotta Watch) The Holy Ghost | 4:45 | Play |

| Doxology | 3:21 | Play |

| Recessional: “The Glory Train” | 7:34 | Play |

| Benediction | 1:27 | Play |

| Amen | 8:20 | Play |

Liner Notes

The Ministry of Jazz

By Leon Wieseltier

There is a sense in which jazz is a supremely secular art, the very sound of secularism. In jazz one hears only human powers – the pulsings of the vainglorious city, the self-reliance of the improvising mind, the articulation of inner logics, the orchestration of seductions, emotions refined by structures, trains and buses, brothels and nightclubs, arguments and confessions – the whole magnificent enterprise of the search for human meanings in an immanent world solely by means of musical forms. The jazz musician is a man or woman left to his or her own devices, and to the devices of the jazz tradition. The improvising musician demonstrates by example the improvisatory character of existence. There is inspiration, but there is no revelation. No prophet comes to teach anybody how or what to play. There is soulfulness, but without the metaphysics. Jazz is exhilaratingly profane, which may account for its canonical status as the musical idiom of modernity.

And yet there has been sacred music, beautiful sacred music, in jazz. This goes back to its very provenance. Its origins in the blues gave jazz an origin in the church. “In point of fact,” Albert Murray observed, “the highest praise given a blues musician has been the declaration that he can make a dance hall rock and roll like a downhome church during revival time.” If the subject of the blues is melancholy and its overcoming, then the blues has a natural ally in the church, where people enter dejected and leave undejected, and men and women who have been laid low are raised high without any deception about the reality of pain. The same sort of people go to jazz clubs and jazz concerts for the same sort of reasons: to hear difficulties worked out and impediments transformed into opportunities for creation. Religious feelings often find a home in unreligious forms – and when they do, who is to say that the forms are not religious? There are secular compositions, and jazz compositions, that confer upon the listener a sense of tranquility so overwhelming that it can only be called divine. (Horace Silver’s “Peace,” or certain passages in Coltrane, or Wynton Marsalis’ “Let Us Pray.”) The secular and the religious run into each other like paints mixing on a palette. The boundaries between them are inevitably porous, because they must both minister to the same human needs.

In the Western musical tradition, secular music has always permeated sacred music. Music, like wine, can be consecrated. Josquin made sublime masses out of the most vernacular materials. Haydn’s masses have a worldly sound but an otherworldly purpose – and in this respect they are like us, who inhabit all the realms, the streets and the clouds, within a single identity. The spiritual versatility of aesthetic form is also evident in the sacred compositions of the jazz tradition. In 1954, for example, Mary Lou Williams underwent a religious transformation and began a period of reflection that culminated three years later with her acceptance into the Roman Catholic Church. Not long afterwards she produced a remarkable composition called “St. Martin de Porres,” for a small mixed chorus and piano. The piece is a hymn to a mulatto saint of seventeenth-century Peru, whom it addresses as the “Black Christ of the Andes.” It is almost entirely a cappella, as Williams deploys her legendarily sophisticated harmonic understanding in the service of her veneration – and then, almost at the very end of the lush modernist polyphony, her piano suddenly enters with an intoxicating groove that could not be more removed in time and place and mood from the antique monkish piety that it celebrates. What unifies these disparate elements into an aesthetic whole is the force of the composer’s spiritual intention. To explain the liturgical pieces that she was writing in the jazz style, Williams wrote a short guide to her ideas, which included this: “The Spiritual Feeling: The Characteristic of Good Jazz. The spiritual feeling, the deep conversation, and the mental telepathy going on between bass, drums, and a number of soloists are the permanent characteristics of good jazz. The conversation can be of any type, exciting, soulful, or even humorous debating.” Of any type, but all for the greater glory of God.

In this aspect of the art as in many others, it was Duke Ellington who set the standard, and established the friendship between jazz and God most gorgeously and definitively. Between 1965 and 1973 he composed and performed three Sacred Concerts. He distinguished them from “the traditional mass jazzed up.” (He was commissioned to write a mass but it seems never to have been completed.) They were instead suites of pieces for his orchestra and large choirs, in which various churchly moods – solitude (an old Ellingtonian theme), humility, desolation, affirmation, joy – were expressed in various rhythms and colors, all of them intensely lyrical: the blues with an unmistakable echo of the numinous. The jazz audience has always had trouble with the late works of jazz masters – Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Lester Young: all were said to have fallen off in their final years – and Ellington was no exception; but in Ellington’s case, as with the others, this is an egregious mistake. Some of Ellington’s religious music is profoundly affecting, and it has the ripeness of insight and expression that only late works can possess. In other contexts we call this lateness wisdom.

“I think of myself as a messenger boy,” Ellington declared about his sacred compositions, “one who tries to bring messages to people.”He undertook these works “not as a matter of career, but in response to a growing understanding of my own vocation.” In this regard he brings to mind Rossini, another genius of mirth and elegance and pride, another revolutionary of musical arrangement, who turned to liturgical composition in his later years and produced a “petite messe solonelle” that summed up his methods and his love of life and sealed them together with a heavenward look. The people to whom the jazz evangelist Ellington brought his message were “not people who have never heard of God, but those who were more or less raised with the guidance of the Church.” In his notes to the Second Sacred Concert, which like his other works of this kind was performed in churches, he was rather scalding about unbelievers: “I hate to say that they are out-and-out liars, but I believe they think it fashionable to speak like that… They snicker in the dark as they tremble with fright.” The tone is jarring: nastiness is such an unEllingtonian mode. It is important to note, therefore, that his sacred works themselves are mercifully devoid of such brimstone, and there is nothing stylistically orthodox about them, though Ellington’s point about the unfashionability of faith in the precincts of high culture is still correct.

The magnanimity of spirit that was a hallmark of all of Ellington’s music appears in a statement of principle that he produced to accompany his first Sacred Concert in 1965. “There are people who speak one language and some who speak many languages,” he wrote. “Every man prays in his own language, and there is no language that God does not understand.” Here is the universalism, the definitional inclusiveness, of the monotheistic God, though it is frequently honored in the breach by many of His believers. The legitimacy of jazz as an address to God, Ellington suggests, is beyond question, because there are no illegitimate addresses to God. Every human language is suitable for the delineation of human finitude and its appetite for transcendence. Of any type, as Mary Lou Williams taught. Or as the prophet Isaiah proclaimed, in a verse that figures significantly in Wynton Marsalis’ Abyssinian Mass, “For my house shall be called a house of prayer for all the nations.”

Indeed, the sense of cosmic scale that is conveyed by religion may promote in us a preference for modesty of expression, for a humble and even inarticulate voice. Ellington continues, inventing a Hasidic parable of his own: “It has been said once that a man who could not play the organ or any of the instruments of the symphony accompanied his worship by juggling. He was not the world’s greatest juggler, but it was the one thing that he did best. And so it was accepted by God.” Jazz is a juggle, prayer is a juggle, existence is a juggle. The juggler is an artist of rises and falls whose medium is the air. He works with more than he can handle, but he handles it. What he drops he picks right up, and swiftly enough to prevent a disruption of the flow of the elements. The quality of his soul is established by his perseverance, his grace, his training, his wit, his precision, his cool, his familiarity with the experience of failure and recovery. He, the common juggler, is a spiritual figure.

Yet there was nothing aesthetically modest about Ellington’s sacred pieces. His principle of inclusion was both philosophical and structural, and the same may be said of Marsalis’ Abyssinian Mass, which is a formidable heir to Ellington’s ecclesiastical breakthroughs. Unlike its precursors, this work is a “traditional mass jazzed up.” It was composed in partnership with a minister and for a church, the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, a congregation that was founded in 1808 in protest against racially segregated seating in the First Baptist Church of New York. (The breakaway parishioners included Ethiopian sailors, who gave their country’s name to the new institution.) Marsalis has produced music for a full liturgy: the first thing one notices about this work is its magnitude. The mass is massive. In Marsalis’ sweet amplification of the prophet’s verse, this house of prayer is “for all, all, all, all nations.” And for all, all, all, all states of the soul. “Everyone has a place in the House of God.”

The Abyssinian Mass falls into the time-honored current of sacred music that seeks to represent the tremendous abundance of the religious universe, inner and outer. This is not an austere devotion. It is a plenitude of musical forms for a plenitude of spiritual circumstances. It describes lowliness and it describes grandeur, and it describes the grandeur in lowliness. It traverses theology (“Now he sits at the right hand of God / Waiting to judge the quick and the dead”) and sociology (“Stop by the hospitals. Set the wrongly imprisoned free”). Like the Psalmist, it finds God everywhere. And the ubiquity of God demands a great deal of music. Musically, too, Marsalis’ offering is vast and multifarious: so many styles of African-American music, from the rollicking to the suave, contribute to these supplications and exclamations. The intellectual and compositional range for which Marsalis is renowned is amply in evidence here, the breathtaking diversity of rhythms and harmonies, infectious even when esoteric. Marsalis has a rare gift for making joy out of complexity. In The Abyssinian Mass he has joined intellectuality to enthusiasm, the thought to the shout.

Though it has been performed in concert halls (I attended one of those performances in 2013), The Abyssinian Mass is most emphatically a prayer service – an African-American prayer service. The African American church is a temple of participation and a theater of immersion. It offers not a theory of religious experience, or a prescription for religious experience, but religious experience itself. Its program is arousal and catharsis and excitement and transfiguration – the movement of souls by the movement of voices and bodies, by turns tender and ferocious. It fully expects commotion from an awakening individual. The music of the church is the articulation of that commotion, which leads through agitation to bliss. Jazz, blues, or gospel, the objective of this music is the acquisition of an inner confidence, a fortifying light that is fully the match of the darkness that waits outside. The Abyssinian Mass is a perfect score for this practice of renewal.

The bestirring of the individual in the church, his ascent from the ordinary to the extraordinary, from the prosaic to the poetic, does not occur in solitariness. The unit of the revival is the congregation, the community; and the musical symbol of this shared spirituality, of the togetherness that lifts the individual above the miseries of individuation, is the choir, the chorus. The African American chorus is the antithesis of the Greek chorus.

The Greek chorus is detached, explanatory, chilling, a standpoint away from the dramatic and psychological action. The African American chorus is attached, participatory, thrilling, in the heart of the dramatic and psychological action. It stands for, and with, the congregation, melting in the same passions, answering to the same summons. Perhaps the greatest achievement of The Abyssinian Mass is Marsalis’ choral writing. The demotic integrity of his words – this is a mass for everyday people; Marsalis wrote it for his grandmother and his great-aunt, both of them domestic workers and devout – is brilliantly intensified by the chromaticism of their settings. The humanism of the work is most generously established by its belief in the holiness of the human voice.

In the history of religion, there have been two avenues of approach to the divine: away from the senses and through the senses. There have been believers who held that the material world is a great obstacle to the advancement of the spirit, and that material expressions of the divine should be denied and even destroyed, because they contradict the sublimity of God. And there have been believers who held that the spirit cannot arrive at the invisible except by means of the visible, at the inaudible except by means of the audible, and so God’s incorporeality must make a concession to our corporeality and permit us to reach what we cannot see and hear by means of what we can see and hear. The former were known in the Byzantine world as iconoclasts, or smashers of the icons, and in the Counter-Reformation in Europe they cracked down on the pleasures of polyphony, and in the Islamic world in our own time they blow up ancient sites and statues that they regard as idolatrous. The latter, the ones who defended the icons, the artistic representations of God, were in the Byzantine controversies known as iconodules. From our rich heritage of sacred painting and sacred music, we may justly conclude that the iconodules won. The association of beauty with divinity has survived the enemies of beauty and the enemies of divinity. And even the doubters, when they see the great pictures and hear the great pieces, are lifted up, wherever their heights are. True or false, faith gave us all this art. Hallelujah!

Credits

DISC 1

1. DEVOTIONAL 8:34

Vincent Gardner – trombone, featured; Jamal Moore – bass (vocal solo); Chris Crenshaw – trombone, featured; Marvin Lowe – tenor (vocal solo); Christine Fanuel – soprano (vocal solo); Elliot Mason – trombone, featured

2. CALL TO WORSHIP 5:11

Ryan Kisor – trumpet, featured; Kaleb Alexander Hopkins – tenor (vocal solo); Marcus Printup – trumpet, featured; Matia Washington – alto (vocal solo); Kenny Rampton – trumpet, featured; Quinn Brown – tenor (vocal solo); Wynton Marsalis – trumpet; Marcus Printup; Kenny Rampton; Ryan Kisor; Dan Nimmer – piano

3. THE LORD’S PRAYER 4:13

Dan Nimmer; Stephanie Estep – soprano (vocal solo); Jonathan Kirkland – bass (vocal solo)

4. PROCESSIONAL:“WE ARE ON OUR WAY” 7:25

Chris Crenshaw – trombone; Elliot Mason; Marcus Printup; Ryan Kisor; Victor Goines – Eb clarinet; Walter Blanding – tenor saxophone; Kenny Rampton

5. INVOCATION AND CHANT 6:29

Vincent Gardner – tenor (vocal solo) and trombone; Victor Goines – clarinet

6. RESPONSIVE READING, MATTHEW 5:3-12 THE BEATITUDES 7:57

Walter Blanding – tenor saxophone (intermittent soloing); Matia Washington – alto (vocal solo); Martin Bakari – tenor (vocal solo); Lauren Dawson – alto (vocal solo); Martin Bakari – tenor (vocal solo); Clayton Brown – tenor (vocal solo); Kali Wilder – alto (vocal solo); Victor Goines – clarinet; Jamal Moore – bass (vocal solo); Jorell Williams – bass (vocal solo); Elaine Sturkey – soprano (vocal solo); Ted Nash – flute; Kali Wilder – soprano (vocal solo); Marquita Raley – alto (vocal solo); Dan Nimmer; Kali Wilder – soprano (vocal solo); Marquita Raley – alto (vocal solo); Matia Washington – alto (vocal solo); Ali Jackson – variety of two grooves, featured (washboard/tambourine, drums)

7. GLORIA PATRI 5:05

Saxophone soli; Dan Nimmer; Trombone soli

8. PRAYER: “PASTORAL PRAYER” 13:05

Dan Nimmer, featured; Djore Nance – bass (vocal solo); Patrice Eaton – soprano (vocal solo); Djore Nance – tenor (vocal solo); Wynton Marsalis – trumpet hollers; Marcus Printup, featured; Chris Crenshaw – recitation; Paul Nedzela – baritone saxophone, featured; Ali Jackson – recitation; Victor Goines – soprano saxophone, featured; Vincent Gardner – recitation; Sherman Irby – alto saxo- phone; Ryan Kisor; Nicole Phifer – alto (vocal solo); Wynton Marsalis; Ryan Kisor; Nicole Phifer – alto (vocal solo)

9. CHORAL RESPONSE: “THROUGH HIM I’VE COME TO SEE” 2:21

Chorale Le Chateau (women only)

10. ANTHEM: “GLORY TO GOD IN THE HIGHEST” 7:01

Ali Jackson – sanctified tambourine, featured; Marcus Printup; Ted Nash – flute; Elliot Mason; Wynton Marsalis; Vincent Gardner – trombone; Ryan Kisor

DISC 2

11. SCRIPTURE: ISAIAH 56:7 2:36

Ali Jackson; Rasul A-Salaam – tenor (vocal solo); Ted Nash – flute

12. MEDITATION:“LORD HAVE MERCY” 4:59

Carlos Henriquez – bass, featured

13. SERMON: “THE UNIFYING POWER OF PRAYER” – PART I: “THIS HOUSE IS GOD’S HOUSE” 4:17

Damien Sneed – Hammond organ; Victor Goines – clarinet; Marcus Printup, featured; Reverend Dr. Calvin O. Butts,

III – sermon

14. SERMON: “THE UNIFYING POWER OF PRAYER” – PART II: “THE POWER OF PRAYER” 4:57

Reverend Dr. Calvin O. Butts, III – sermon; Wynton Marsalis; Marcus Printup; Kenny Rampton

15. SERMON: “THE UNIFYING POWER OF PRAYER” – PART III: “EVERYONE HAS A PLACE” 3:15

Reverend Dr. Calvin O. Butts, III – sermon; Dan Nimmer, featured; Paul Nedzela – baritone saxophone, featured

16. INVITATION: “COME AND JOIN THE ARMY” 4:33

Chris Crenshaw – spoons; Carlos Henriquez – cowbell; Quinn Brown – lead tenor (vocal solo); Rafael Clarke – bass (vocal solo); Josh Adam Dawson – tenor (vocal solo);

Derrick Baskin – tenor (vocal solo); Vincent Gardner – tuba, featured; Ted Nash – piccolo; Ali Jackson

17. OFFERTORY: THE FATHER 2:39

Marcus Printup; Kenny Rampton

18. OFFERTORY: THE SON 3:22

Wynton Marsalis

19. OFFERTORY: (YOU GOTTA WATCH) THE HOLY GHOST 4:45

Sherman Irby – alto saxophone; Chris Crenshaw; Marcus Printup

20. DOXOLOGY 3:21

Chorale Le Chateau

21. RECESSIONAL: “THE GLORY TRAIN” 7:34

Kenny Rampton; Sherman Irby – alto saxophone; Victor Goines – clarinet

22. BENEDICTION 1:27

Chris Crenshaw – tenor (vocal solo); Dan Nimmer

23. AMEN 8:20

Walter Blanding – tenor saxophone; Victor Goines – tenor saxophone; Jorell Williams – bass (vocal solo);

Nicole Phifer – alto (vocal solo); Vincent Gardner – “African Bull Horn” trombone holler

THE ABYSSINIAN MASS

Jazz At Lincoln Center Orchestra With Wynton Marsalis Featuring Damien Sneed And Chorale Le Chateau

CHORALE LE CHATEAU

Rasul A-Salaam, Justin Michael Austin, Martin Bakari, Derrick Baskin, Jeanette Blakeney, Clayton Brown, Quinn Brown, Chenee Campbell, Joe Caruncho Jr., Rafael Clark, Emily Dankworth, Tynan Davis, Josh Adam Dawson, Lauren Dawson, George Dowdy, Sequina Dubose, Patrice Eaton, Patricia Pates Eaton, Stephanie Estep, Christine Fanuel, Eustacia Foster, Shani Foster, Ayana George, Maryvel Gonzalez, Jamal Green, Amber Harris, Kaleb Alexander Hopkins, Candice Hoyes, Clinton Ingram, Arielle Jacobs, Michael Jahlil, Edward Jordan, Jonathan Kirkland, Tesia Kwarteng, Latoya Lewis, Marvin Lowe, Maria Marsalis, Ann McCormack, Richard McMichael, Lynette Rhett McNeil, Lauren Michelle, Jamal Moore, Belinda Munro, Djore Nance, Darnell Norman, Jonathan Owens, Nicole Phifer, Marquita Raley, John Rawlins Ill, Brittany Robinson, Cameron James Ross, Timothy Springs, Quiana Smith, Travis Smith, Karyn Stevenson, Sharol Stone, Gabrielle Stravelli, Elaine Sturkey, Brandie Sutton, Jennalyn Thomas, Nathaniel Thompson, Tonya Thompson, Bobby W. Walker, Joanna Wallfisch, Matia Washington, Montavius Wells, Kortland Whalum, Kali Wilder, Jorell Williams, Allyson Wilson

ORATOR

Reverend Dr. Calvin O. Butts, III

An Original Composition by Wynton Marsalis

(Skayne’s Music/ASCAP)

Executive Producer: Wynton Marsalis

Producer: Gabrielle Armand

Post Producer and Mixing Engineer: Todd Whitelock

Mixed in Studio B at MSR Studios, NYC

Assistant Mix Engineer: Alex Hendrickson

Live Mix Engineer: David Robinson

Live Recording Engineers: Rob Macomber, James P. Nichols

Mastered by Mark Wilder at Battery Studios, NYC 2016

Art Direction and Design: Frank Harkins

Photography: Frank Stewart

Essay: Leon Wieseltier

Copyists: Jonathan Kelly, Geoff Burke, Matt Hilgenberg, Rigdzin Collins

Music Administration: Kay Wolff, Christi English, Omar Little, Tim Carter, Alex Ball

Marketing: Aaron Bisman, Jake Cohen, Jonathan Fricke

Publicity: Zooey Tidal Jones, Christina Riley

Project Management: Valerie Florville

DVD Producers: Eugenia Han, Sophia Betz

DVD Directors: James Sapione, Simeon Marsalis

The mission of Jazz at Lincoln Center is to entertain, enrich and expand a global community for jazz through performance, education and advocacy.

ABYSSINIAN: A GOSPEL CELEBRATION TOUR (2013)

JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER TOUR STAFF (2013)

Raymond Murphy, Tour Manager

David Robinson, Production Manager

Eric D. Wright, Assistant Director

Alex Knowlton, Manager

Kay Wolff, Associate Director, Music Administration

Christi English, Manager, Music Administration

Frank Stewart, Senior Photographer

Charles Bratton, Driver

Ernie Gregory, Driver

Jay Sgroi, Tour Assistant

JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER NY CONCERT STAFF (2013)

Zakaria Al-Alami, Scenic and Lighting Designer

Billy Banks, Stage Manager

Sarah Peterson, Production Manager

CHORALE LE CHATEAU TOURING STAFF

Damien Sneed, Conductor

Cynthia Ellis, Personal Assistant to Damien Sneed

Karyn Stevenson, Executive Administrator

Quinn Brown, Executive Administrator

Jorell Williams, General Assistant

Elaine Sturkey, General Assistant

Laina Sweetney, General Assistant

Karla Scott – Educational Workshop Leader

Gwendolyn Quinn – Public Relations

THANK YOU:

Jazz at Lincoln Center, Damien Sneed, and Chorale Le Chateau would like to thank all of the tour presenters, promoters, churches, music and community centers, schools, radio stations and volunteers for their generosity, down-home hospitality and support throughout our tour.

Special thanks to The Abyssinian Baptist Church and Ricky ‘Dirty Red’ Gordon

Special thanks to the David Steward Family Foundation for their faith in a work that they had not yet heard.

FUNDERS OF ABYSSINIAN: A GOSPEL CELEBRATION TOUR (2013) LEADERS

World Wide Technology Foundation Dalio Foundation

The Jay Pritzker Foundation Louise and Leonard Riggio BENEFACTOR

John S. & James L. Knight Foundation

SUSTAINER

AT&T

FRIENDS

Sam and Marilyn Fox

Andy and Barbara Taylor

PATRONS

George Herbert Walker Foundation

Margie Imo/Imo’s Pizza

Rich McClure/UniGroup

Rob Goldstein/Alter Trading

Steve Schankman/Contemporary

Productions Steve Maritz/Maritz

Personnel

- Ali Jackson – drums, tambourine

- Carlos Henriquez – bass

- Dan Nimmer – piano

- Kenny Rampton – trumpet

- Ryan Kisor – trumpet

- Marcus Printup – trumpet

- Vincent Gardner – trombone

- Chris Crenshaw – trombone

- Elliot Mason – trombone

- Victor Goines – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet, bass clarinet

- Ted Nash – alto sax, soprano sax, clarinet, flute, piccolo

- Sherman Irby – alto sax, soprano sax, clarinet, flute

- Walter Blanding – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet

- Paul Nedzela – baritone sax, bass clarinet

- Damien Sneed – choir conductor

Also of Interest

-

Videos

Videos

Everyone Has A Place - A documentary film about Wynton Marsalis’ Abyssinian Mass

-

Videos

Videos

Abyssinian: In Wynton’s Words - Recessional

-

Videos

Videos

Abyssinian: In Wynton’s Words - Meditation

-

Videos

Videos

Abyssinian: In Wynton’s Words - Responsive Reading

-

Videos

Videos

Abyssinian: In Wynton’s Words - Invocation and Chant

-

Videos

Videos

Abyssinian: In Wynton’s Words - Devotional

-

Videos

Videos

Abyssinian: Everyone Has a Place (Part Five)

-

Videos

Videos

Abyssinian: Meditation (Part Four)