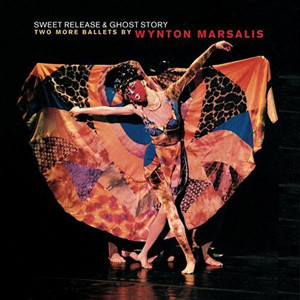

Sweet Release & Ghost Story: Two More Ballets by Wynton Marsalis

Written for Judith Jamison’s choreography for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and performed by the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, SWEET RELEASE tells the story of a man and a woman, represented by the trombone and trumpet, and the temptations that threaten their romance. GHOST STORY was written for a small ensemble – Ted Nash on reeds, Eric Lewis on piano, Carlito Henriquez or Rodney Whitaker on bass, and Jaz Sawyer on drums – to serve as a score for choreography by Zhong Mei Li.

Album Info

| Ensemble | Multiple Ensembles |

|---|---|

| Release Date | August 10th, 1999 |

| Recording Date | August 11, 1996; December 7, 1998 |

| Record Label | Sony Classical |

| Catalogue Number | SK 61690 |

| Formats | CD, Digital Download |

| Genre | Jazz Recordings |

Track Listing

| Track | Length | Preview |

|---|---|---|

| Home: Beyond This Rage – Sweet Release | 7:52 | Play |

| Church: Renewing Vows – Sweet Release | 7:19 | Play |

| Church Basement: Party – Sweet Release | 5:28 | Play |

| Street: Make Room For Me – Sweet Release | 4:23 | Play |

| Home: Give Me Your Hand – Sweet Release | 5:44 | Play |

| Introduction – Ghost Story | 3:10 | Play |

| Acknowledgment – Ghost Story | 5:30 | Play |

| Tango – Ghost Story | 6:21 | Play |

| First Blues – Ghost Story | 2:27 | Play |

| Awakening – Ghost Story | 2:17 | Play |

| Celebration – Ghost Story | 2:33 | Play |

| Second Blues – Ghost Story | 4:17 | Play |

| Recognition and Reconciliation – Ghost Story | 2:33 | Play |

Liner Notes

We have come to expect remarkable things from Wynton Marsalis. He is a signal aesthetic star of serious achievement in our time. This recording, pushing the boulder of a heavy talent for composition farther up the hill, features two works. The first, clearly a masterpiece, is “Sweet Release,” written for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater under the direction of Judith Jamison. The second, “Ghost Story,” something very different in its sound and construction for Marsalis, was composed for Zhongmei Dance under the direction of, well, Zhongmei Li.

“Sweet Release,” like his dance scores for Garth Fagan Dance, the New York City Ballet, and Twyla Tharp, is further proof of the rather obvious fact that Marsalis is the best composer to arrive in jazz music since the death of Duke Ellington in 1974. Though time will surely tattle in much greater detail when the very last Marsalis note has been written, it has been speaking its piece both loudly and subtly over the impressive years of writing.

What Marsalis has done in his time is what Ellington did in his. He has invented a personal la gauge that builds on very perceptive insights into the interpretation of the four fundamental areas of engagement that reappear in the music over and over – the blues, 4/4/ swing, the romantic ballad, and Afro-Hispanic rhythms. From the very first part of “Sweet Release,” this man from New Orleans makes it clear that he is the point rider of the contemporary jazz avant-garde. And that is because his level of engagement remains American and does not use twentieth-century European concert music cliché’s or pop music devices in order to “advance” jazz.

In the first section of “Sweet Release,” for instance, we hear a trumpet vocabulary that stretches back to Freddie Keppard and King Oliver of the twenties and moves up through the co tribulations of Rex Stewart in the thirties while calling upon the kinds of velocity techniques Dizzy Gillespie put in the music during the forties. He also manages to remind us of the trilling, skittering, and percussive romps of Thelonious Monk at the piano! Such combinations only Marsalis is capable of, which is also true of the writing, a dissonant and swinging combination of surprises.

At just under thirty-four minutes, “Sweet Release” is an extraordinarily concise extended work. Everything introduced in the first and second sections – melodically, harmonically, and rhythmically – is recast throughout the remainder of the piece, with the brief third section a contrapuntal combining of the core materials from the previous two parts, both set within the Afro-Hispanic frame that will dominate parts four and five. In all, we hear dissonance and consonance, a polyphony that rises from the New Orleans front line of traditional jazz, dramatic tempo changes, an angularity we have rarely heard utilized so successfully, and a grip on swing that will shake the blues away.

Marsalis knows well how to develop his themes with reiterations or sustained melodic variations, how to bring a harmony we have heard earlier into another position. All of these qualities are evident in the way that “Sweet Release,” beginning with section four, builds up into the next part, creating an ever more complex narrative of contrasting rhythmic, metric, harmonic, and contrapuntal intricacy, all the while giving extension, elaboration, and searing refinement to the writing that featured the trumpet and the trombone in the first through third sections. The ways in which Marsalis musically makes his way back to his initial propositions in the last three parts are precise but illusively magical examples of his brilliance.

Here is the composer’s description of what this music’s all about:

“This music moves on the outline that Judith Jamison gave me for the piece, which was the development of a relationship between a man and a woman. It starts in the morning. I chose to open with the trumpet, using a vocabulary that evolved in New Orleans, which I use to represent the woman waking up, yawning and stretching. We are also exposed to the triangle of her personality. She is vulnerable, coquettish and, if necessary, willing to straighten you, correct you, verbally or physically.

The man is introduced by the trombone of Wycliffe (“Pine Cone,” “Chuck Wagon”) Gordon. He was chosen because he is a master at playing different vocal effects on his horn and because he has tremendous power. None of this obviates his musical ability to execute equally subtle things with the same degree of emotional nuance. The character he portrays is strong, smooth as wet ice, but he also questions himself. He’s not always sure he has it together.

The design of the music renders the interaction between these two male and female personalities. There are a lot of changes in the ground rhythm. This supplies different things that dancers can react to, one way or another. The first movement introduces us to the woman. The second introduces us to the man.

The third, which alternates between two meters, 5/4 and 6/4 and moves on top of a vamp, is about when the man and the woman go to a ritualized wedding, set in the past and in the future, which is why the snake of the clarinet, which means no good to anyone, is appropriate. Wrong and evil step through all doors of time, backwards and forwards.

You have got to watch out for that snake. He’s never satisfied. He’s looking for Adam and he’s looking for Eve. He won’t settle for one. He wants to break the whole groove up. That’s why this section ends with the snake by himself.

The salsa section is about big, big groups of men and women. I turned around the usual sound-image and made the saxophones the men and the brass the women. This is colorful and it uses the full ensemble to celebrate the feeling of a party, with the sensuality that has been elevated to such a high level in Latin dance…What I wanted to get here is the joy and the exuberance that we always feel when we see or do this kind of dancing. The end of this part, which slows down, represents the glowing exhaustion at the end of a great party, where a fine time was surely had by all.

The three of them emerge from this good time with their conflicts still intact. This is the blues in which two people are roped together by a snake. it starts with the clarinet in the bottom, working his way up and bringing hell with him, intent on getting between the two people. Here, in musical terms, we have a reiteration of the traditional New Orleans front line of trumpet, trombone, and clarinet. A series of battles ensues. First the clarinet fights with the man, who is trying to protect the woman. Then the woman comes out in all of her heated grandeur but, like the man, she doesn’t really repel the clarinet. Then the trumpet and the trombone get together and blow the clarinet out. The clarinet, relegated to the lower position, that is, the lower realm of hell, fades away, unhappy because his destructive intentions have been stymied.

The final section is the culmination, the victory of romance over distraction. It has the particular sound we hear because there is no greater joy than the joy felt by a man and woman who have overcome the snakes of disorder, the things that might separate them. When those personalities see each other so clearly that they can no longer forget what attracted them to one another, they move with pure confidence into very, very close circumstances, which can only be expressed increasingly close swing.”

Now that you’ve read the words of the composer himself, all you have to do is get a grip on your groove. If you lack one, don’t worry. You won’t have to wait very long. And you might be surprised to know, as this writer was, that almost every sound is composed, right there on the page, no matter how improvised much of the playing might seem.

For the other work on this disc, “Ghost Story,” Marsalis had the task of using a small ensemble to interact with dancer Zhongmei Li’s choreography, which gave motion to a tale described in the premiere’s program notes as a traditional Chinese ghost story set in a modern context: “In it the portrait of a beautiful woman seems to be brought to life by music and love, but all is illusion. The woman, sensuous and possessed of magical powers, changes identifies and forms, from human to ghost, in the guise of a fox spirit, and bad again. This mysterious story is about deception and thwarted love, a kind of failed collaboration, between figures of different realms, the world of the earth and that of the spirits, of dream and reality, hope and disillusionment.”

The mutation of mood, the risings and the descents, aptly describe a protean ghost, a fore of trickery and an agent of the heartbreak that from having been duped all the way to the bottom of the bucket of the blues. Marsalis uses material that spreads over an expressive spectrum: from what initially seems like no more than a listless set of scalar exercises to a steamy tango, moving from place to place in ways we have not heard from him before. It is an achievement that hasn’t one aural tinge of the counterfeit.

But you better watch out for the grand triumph of that “Sweet Release.” It might upset you. Masterpieces are like that.

– Stanley Crouch

Credits

SWEET RELEASE

Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra

Wynton Marsalis (trumpet, conductor); Wess Anderson (alto and sopranino saxophone, clarinet), Sherman Irby (alto saxophone, clarinet), Victor Goines (tenor and soprano saxophone, clarinet, bass clarinet), Stephen Riley (tenor saxophone), Gideon Feldstein (baritone saxophone, bass clarinet), Roger Ingram (trumpet), Ryan Kisor (trumpet), Russell Gunn (trumpet), Jamil Sharif (trumpet), Wycliffe Gordon (trombone, tuba), Ron Westray (trombone), Wayne Goodman (trombone), Bob Trowers (trombone), Eric Reed (piano), Rodney Whitaker (bass), Herlin Riley (drums), Pernell Saturnino (conga and latin percussion), Stefon Harris (percussion and assistant conductor)

GHOST STORY

Ted Nash (flute, alto and soprano saxophone), Eric Lewis (piano), Carlos Henriquez (bass), Rodney Whitaker (bass); Jaz Sawyer (drums)

Producer: Delfeayo Marsalis

Engineer: Patrick Smith

Second Engineer: Kooster McAllister (tracks 1-5)

Assistant Engineer: Darby (tracks 6-13)

Technician: Roderick Ward (Tracks 6-13)

Mixed at Signet Soundelux, Los Angeles.

Mix Engineer: Patrick Smith

Mix Assistant Engineers: Jesse Eaton & Brian Dixon

Piano provided by Steinway.

Pro-Tools Technician: Michael Dorian (Phrygian)

Bass consultants: Monk 5 by 5 (Steve Reynolds) & Marc Lombardo.

To obtain more wood sound from the bass, this CD was recorded without usage of the dreaded bass direct.

Sweet Release was recorded on August 11, 1996 at Music Hall in Tarrytown, New York.

Ghost Story recorded on December 7, 1998 at Rose Studio, Lincoln Center, New York City.

The producer wishes to thank Mr and Mrs. Ringeisen, Selena Arizanovic, Gretchen Roberts, Milo and Charlie at Glyph, Jimmy Tsai, Dave Dubow, and Pedronimus.

Wess Andersen appears courtesy of Leaning House Records.

Sherman Irby appears courtesy of Blue Note Records.

Vietar Goines appears courtesy of Rosemary Joseph Records.

Russell Gunn appears courtesy of Atlantic Records.

Eric Reed appears courtesy of Verve Music Group.

Stefon Harris appears courtesy of Blue Note Records.

Ted Nash appears courtesy of Arabesque Records.

Sweet Release was commissioned by Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Inc. in collaboration with Jazz at Lincoln Center for Lincoln Center Festival 96, with sustaining support from The New Works Fund of Ailey Partners.

Premiered on August 9, 1996 at the New York State Theater by the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra and The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater,

The Management Ark, Inc.

Santa Fe, MM – Princeton, NJ

Edward C. Arrendell II – Vernon H. Hammond III

Product Manager: Lisa Stevens

Art Direction: Josephine DiDonato

Logo Art: Drue Katoaka

All Ballet Photography: Ellen Crane

Personnel

- Eric Reed – piano

- Wycliffe Gordon – trombone

- Wess “Warmdaddy” Anderson – alto sax, sopranino sax

- Victor Goines – tenor sax, soprano sax, clarinet, bass clarinet

- Herlin Riley – drums, tambourine

- Rodney Whitaker – bass

- Sherman Irby – alto sax, soprano sax, clarinet, flute

- Gideon Feldstein – baritone sax, bass clarinet

- Roger Ingram – trumpet

- Ryan Kisor – trumpet

- Russell Gunn – trumpet

- Ron Westray – trombone

- Wayne Goodman – trombone

- Stefon Harris – vibraphone

- Ted Nash – alto sax, soprano sax, clarinet, flute, piccolo

- Eric Lewis – piano

- Carlos Henriquez – bass

- Stephen Riley – tenor sax

- Jamil Sharif – trumpet

- Bob Trowers – trombone

- Pernell Saturnino – conga, latin percussion

- Jaz Sawyer – drums

Also of Interest

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis on “Ailey Forward” Virtual Season

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis personally compiles and produces “The Spiritual Side of Wynton Marsalis”

-

News

News

Wynton Marsalis: Jazzman on the Run

-

News

News

Big Band, Big Premiere, Big Tour, Big Marsalis

-

News

News

A Mixed Marriage of Ghosts and Jazz

-

News

News

Exuberant Motion And Rollicking Jazz

-

News

News

A Marsalis Sampler, Both Brief and Complex